Why can't our tech billionaires learn anything new?

On Marc Andreessen's "techno-optimist manifesto"

Earlier this week, Marc Andreessen published a new “techno-optimist manifesto.” Reading it felt a lot like walking past preteens wearing Nirvana tshirts or seeing an ad for the Frasier reboot:

“Oh, have we decided it’s 1993 again? I guess I didn’t get the memo.”

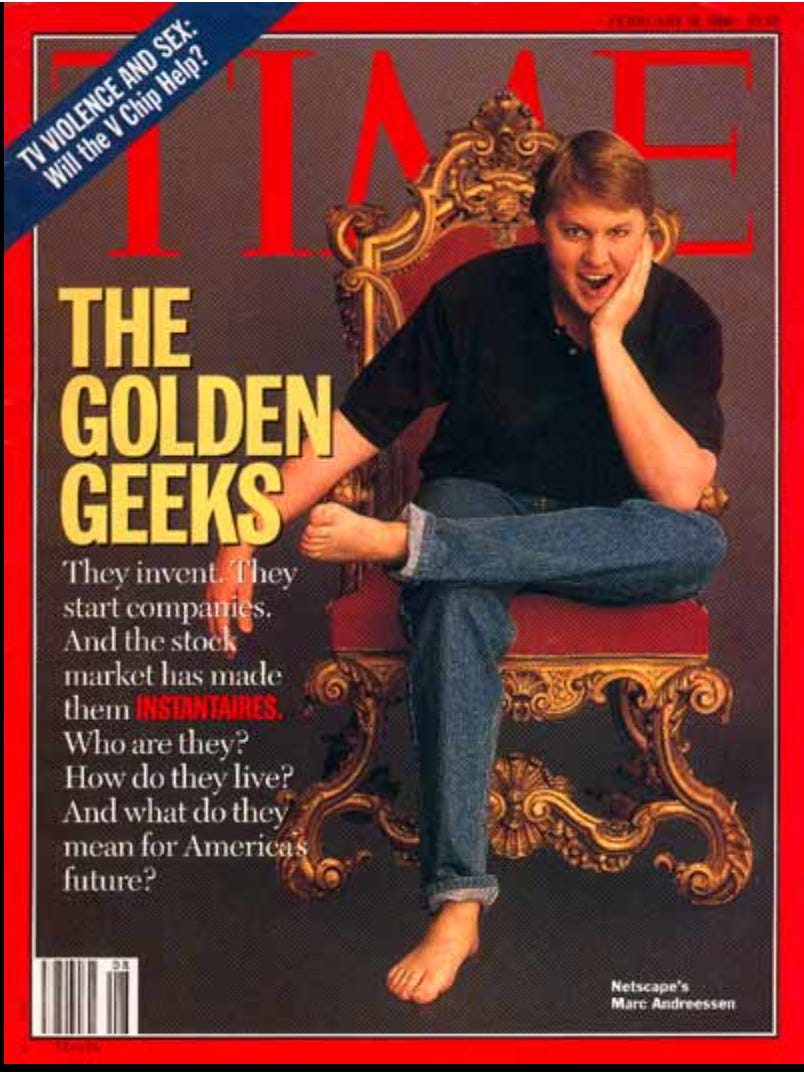

Andreessen is Silicon Valley royalty. He made his first millions as the “boy genius” behind the Netscape web browser in 1995. Later, he cofounded a blue-chip venture capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz (a16z). He has served on Facebook’s board, and invested in many of the other tech “unicorns” of the past decade of rapid wealth accumulation. He is a thought-leader among tech influentials, a member of the elite by any meaningful definition of the word.

In the manifesto (which, let’s be honest, reads more like an extended twitter thread), Andreessen positions himself as a brave, bold truth-teller: “We are being lied to” he declares. “We are told to be angry, bitter, and resentful about technology… Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential… For hundreds of years, we properly glorified this – until recently… It is time, once again, to raise the technology flag. It is time to be Techno-Optimists.”

This is a familiar diatribe. Louis Rossetto used to say exactly the same thing back in WIRED’s startup days. Rossetto insisted that the media and the government were clinging to power by trying to scare people away from the liberatory power of the internet. The only thing that could stop inevitable technological progress was a culture of pessimism and fear. As recently as 2018, Rossetto was calling for a return to “militant optimism,” insisting that the sole barrier to our bright, abundant future is a pessimistic mood. Kevin Kelly, Stewart Brand, and Peter Schwartz all hit similar themes throughout the 90s. Their “Californian Ideology” was a mix of libertarianism and technological optimism, declaring that all of the world’s problems could be solved if we would just sit back and let the engineers of techno-capitalism do their work.

Here’s the question I most wish I could ask him:

Who is lying to us, Marc? You serve on the boards of trillion-dollar companies. A few of your peers own media companies. A few others have chosen to bankrupt media companies that write mean things about them. You have been celebrated for thirty years as the genius-inventors-of-the-future. If the public is turning against you, who ought to be held responsible for such a change in the public mood?

That old WIRED ideology hasn’t aged well. But the 90’s techno-optimists at least a few things working in their favor:

(1) It was the end of the Cold War. The defining global conflict of the late 20th century had ended, and it seemed like we were entering uncharted territory. The underlying thesis was now that global capitalism has truly been unshackled, it will work roughly as well as the libertarian economists tell us it should.

(2) The commercial internet was still in its infancy. We could judge it based only on its potential, rather than its results.

(3) "Big tech” was still pretty niche. Paul Ford captured this nicely in his 2019 essay, “Why I (Still) Love Tech”

We never expected to take over the world! It was just a scene. You know how U2 was a little band in Ireland with some good albums, and over time grew into this huge, world-spanning band-as-brand with stadium shows with giant robotic structures, and Bono was hanging out with Paul Wolfowitz? Tech is like that, but it just kept going. Imagine if you were really into the group Swervedriver in the mid-’90s but by 2019 someone was on CNBC telling you that Swervedriver represented, I don’t know, 10 percent of global economic growth, outpacing returns in oil and lumber. That’s the tech industry.

What makes Andreessen’s 90’s retread so odd is the way he frames it as a challenge to the status quo. Technological optimism has been the dominant paradigm throughout my adult life. We have spent decades clapping for Andreessen and his buddies. We have put them on magazine covers. We stopped regulating tech monopolies. We cut taxes for the wealthy. We trusted that they had some keen insight into what the oncoming future would look like. We assumed that the tech barons ultimately had our best interests at heart.

Even amidst the techlash years, public criticism of the tech platforms ultimately amounted to very little. The ranks of the tech billionaires grew. The largest companies that we associate with digital technology reached trillion-dollar valuations. Their every announcement of a bold new technological future was treated with extraordinary credulity. (remember the metaverse? Remember Web3?)

The most powerful people in the world (people like Andreessen!) are optimists. And therein lies the problem: Look around. Their optimism has not helped matters much. The sort of technological optimism that Andreessen is asking for is a shield. He is insisting that we judge the tech barons based on their lofty ambitions, instead of their track records.

It has been thirty years. The Internet isn’t just the realm of the future anymore. It is also our present and has a substantial past. It is worth examining how the past promises of those 90s techno-optimists worked out.

They promised that technology would solve our environmental problems. And there has, just recently, been some real progress in clean tech. But the trend lines are somewhere between bad and cataclysmic. We do not inhabit the future they insisted they were building. For Andreessen, in 2023, to declare that “there is no material problem – whether created by nature or by technology – that cannot be solved with more technology” is an act of willful self-deception. Just how long are we supposed to clap-and-wait while Andreessen’s investment portfolio tries to science the shit out of the climate crisis?

(That line in the manifesto also reads like an unintentional homage to Homer Simpson, btw. Marc Andreessen is worth something like $1.7 billion. He should hire an editor.):

The 90s tech optimists also insisted that the rising economic tide would lift all boats. Trust in the markets and the markets shall provide. Let us all enjoy the bounty of deregulation. What we’ve been left with is the largest wealth gap since the 1920s. It turns out that when we stopped taxing the billionaires’ preferred investment vehicles, we ended up with a lot more billionaires. Andreessen and his buddies have now amassed so much wealth that they can accidentally set off a bank run through a WhatsApp text message chain. That’s bad.

(Y’know what the grimmest part of reading old WIRED magazines is? It’s the occasional references to housing costs. People could still afford to buy homes back then.)

Economic inequality does not solve itself. Markets are not perfect, self-correcting mechanisms. At one point, Andreessen writes “The market naturally disciplines (…) Markets prevent monopolies and cartels.” I take this as evidence that he doesn’t read any actual economists. One could make an argument that the 90s techno-optimists did not yet know any better (we were just trying global capitalism for the first time, maybe it’d work great!). But, for a Silicon Valley set that likes to pretend at being hardcore Bayesian rationalists, there is something downright comical about how they have managed, across the past thirty years, not to update a single one of their priors.

And this is especially galling coming from a16z, the VC firm most responsible for inflating the Web3 hype balloon. Marc Andreessen and his partners spent the past three years promoting companies like the Bored Ape Yacht Club and Axie Infinity. They were early investors in both companies, so their investments likely paid off handsomely. The company is STILL trying to pump its Web3 investment portfolio.

The reason why people are calling for more regulation of a16z’s investments isn’t because they’ve been “told to be angry, bitter, and resentful about technology.”

It’s because retail investors lost their life savings just last year by throwing cash at the Ponzi schemes that a16z was actively hawking.

(Marc Andreessen should really consider taking the “have an ounce of fucking shame” challenge.)

Andreessen’s broader narrative of technological progress also deserves some proper heckling. He describes “technology” as if it was an innate force that can either be accelerated or decelerated. It’s as if we have a single knob that can be adjusted up or down.

Andreessen styles himself an “accelerationist.” He labels his opponents as “decelerationists.” Decelerationists are the enemies of progress. He writes “We believe any deceleration of AI will cost lives. Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.”

This is just a comically oversimplified view of technology. It's narrow and it's self-serving. Technology isn't a dial. (Of course it isn't a fucking dial. How old are you, Marc? Seven? Are you seven?)

With the benefit of hindsight, we can roughly approximate the pace of technological development — Brad Delong does a nice job of this in Slouching Toward Utopia, a book that Andreessen recommends but obviously has not actually read. But we can also affect the direction of technological development. Technological “progress” does not occur along a single, fixed path. Its course is heavily influenced by people, existing institutions, and incentives.

Take AI as an example: Our options are not limited to “Fast AI” vs “Slow AI.” You get a different variation on the future of AI if, for instance, the biggest financial payoffs are in military applications vs workbench science applications. You get different variations if we demand that machine learning systems be auditable for biased datasets before they are deployed by large government agencies vs if you just trust the tech vendors’ market materials and assume it will all work itself out eventually. If you really want “Fast AI,” probably the best thing you can do is throw piles of government money at increasing the capacity of GPU chip manufacturers. One could conceivably do that while also creating regulatory guardrails that protect copyright, patient privacy, and evaluate (low probability) existential risk concerns. We have a lot of agency here, beyond “fast vs slow.”

Charismatic technologists like Andreessen like to imagine that technological advances are solely authored by courageous inventors and the scrappy companies they found. But that’s a childlike fantasy. It has never been even a little bit true. Silicon Valley was built of public largesse during the Space Race! Venture Capital was an outgrowth of changes to 1970s tax policy. Tesla wouldn’t exist without California’s emissions trading scheme. The beautiful thing about the Inflation Reduction Act is that it’s essentially just a huge pile of money, intended to speed up the clean energy transition.

It follows that one way we could turn the proverbial technology dial up to eleven is by massively increasing our public subsidies for scientific research. Change our tax policies so they stop favoring the billionaire class. Reduce income inequality and invest those tax receipts in massive challenge-grants and/or prizes. Quintuple the size of the NSF! Andreessen would surely object that “the market” is a purer mechanism for technological advancement. But Andreessen’s notion of “the market” is a childlike fantasy.

Andreessen occasionally waxes poetic in the manifesto, writing,

"We believe in the romance of technology, of industry. The eros of the train, the car, the electric light, the skyscraper. And the microchip, the neural network, the rocket, the split atom.

We believe in adventure. Undertaking the Hero’s Journey, rebelling against the status quo, mapping uncharted territory, conquering dragons, and bringing home the spoils for our community."

To paraphrase a manifesto of a different time and place: “Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Technology must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.”

Let me remind you that Marc Andreessen is an exceptionally rich guy in his 50s. He’s about the same age as Elon Musk. And, like Elon Musk’s antics, this whole exercise reeks of a tech billionaire mid-life crisis. I mean…“We believe in the Hero’s Journey?!?”

What do you get for the tech billionaire who has literally everything? The cherished startup vibes of his youth. It’s literally the only thing he doesn’t have anymore.

(Also, that “manifesto of a different time and place” is the Futurist Manifesto, written in 1909 by Italian poet F.T. Marinetti. A decade later, Marinetti would be a principal author of the Fascist Manifesto. Andreessen also approvingly quotes accelerationist/neo-reactionary philosopher Nick Land. He’s kind of saying the quiet part out loud there — these are anti-democratic fascists, of the sort that dip pretty quickly into eugenicist and ethnonationalist fantasies. If you’re curious who Andreessen views as helpful fellow travelers, he sure ain’t hiding it.)

I also want to spare a few words for Andreessen’s “enemies” list.

Among the assorted enemies Andreessen identifies, he singles out “sustainable development goals,” “social responsibility,” “stakeholder capitalism,” “Precautionary Principle,” “trust and safety,” “tech ethics,” and “risk management.”

He also takes a shot at the ivory tower, writing:

Our enemy is the ivory tower, the know-it-all credentialed expert worldview, indulging in abstract theories, luxury beliefs, social engineering, disconnected from the real world, delusional, unelected, and unaccountable – playing God with everyone else’s lives, with total insulation from the consequences.

I’ll leave this one to Kieran Healy:

But really, THESE are the powerful forces undermining technological progress and causing you to write a 5,000 word manifesto? Trust and safety? Stakeholder capitalism? Risk management?!?

..Look, I get that Trust and Safety isn’t any tech CEO’s favorite department. Risk management doesn’t feel like the the Hero’s Journey.

But Trust and safety professionals are not technological pessimists. They are technological pragmatists. And that’s a distinction worth dwelling on. As it happens, I wrote an entire essay on technological pragmatism eight months ago. (One benefit of Andreessen rehashing a bunch of 90s tech ideas is that my WIRED archival research project has generated a ton of useful pre-buttals.)

I’m going to give myself a light writing break by self-quoting a few relevant passages below:

There’s a well-worn tendency to treat every new technological development as either a sign of impending liberation or imminent doom. Tech pessimists tend to be invested in moral panics — warning that “Google is making us stupid” or misinformation is the end of democracy I usually take issue with such characterizations. (As I tell my students at the beginning of every semester, the answer to every question worth asking is “well, it’s complicated.”)

I have at times labeled myself a “worrier.” I think that democracy is fragile, human social systems are complicated, and the state of society only improves through sustained, intentional, collective effort. New technologies are neither our savior nor our doom. They are, instead, catalysts of change. The direction of that change is determined through design choices, and through the social forces of existing institutional arrangements, financial incentives, and power structures.

In place of tech pessimism, I discuss the alternative tradition (borrowing from the late, great James Carey) of technological pragmatism. Rather than adopting the false dichotomy of optimism vs pessimism, technological pragmatism is a perspective that takes fragility quite seriously, inviting questions like:

(1) how do these technologies actually work? What are their actually-existing capacities and limitations?

(2) how are they likely to be incorporated into existing social practices? What economic, political, and cultural practices will they amplify? What will they disrupt? How will the existing institutional forces of money and power warp their deployment?

(3) who is positioned to do what to alter this likely trajectory? Which possibilities ought to be promoted or foreclosed, and through what means?

It’s an intellectual orientation, in other words, purpose-built for worriers and planners. It focuses on the present. It draws historical analogues and comparison. It focuses more on the near-future (which we can plan for) rather than the distant-future (which we mostly construct fantastical stories about).

One can take a more-optimistic or more-pessimistic approach to such pragmatic questions. But focusing on pragmatics reorients how we engage with social, political, and technological change. It strikes me as a less openly ideological endeavor.

It stands out to me that, in Andreessen’s manifesto, there is very little that he wants the public to do. He wants us to shed our doubts, to free our minds, to join him in techno-optimism (“The water is warm. Become our allies in the pursuit of technology, abundance, and life.”). But, as a practical matter, that amounts to little more than a Tinkerbell mindset. Just clap harder.

Andreessen spends 4,000+ words warning about the plague of pessimism that is sweeping the land, and then he finally lists the villains who are responsible and… a lot of them are tech workers, employed by Silicon Valley, but focused on the type of hard practical questions that bum him out.

Technological pragmatism empowers a lot more people than Silicon Valley’s investors, entrepreneurs, and engineers. Regulators and elected officials and everyday citizens have roles to play as well. It isn’t a Hero’s Journey at all.

I suspect that Andreessen is conflating pragmatists and pessimists because the pragmatic questions demand answers and he doesn’t have any. “Just clap harder” is not much of an answer to… any question worth asking.

This all brings to mind Brian Merchant’s fantastic new book on the Luddites, Blood in the Machine (my review is here. Buy the book here.). Merchant’s whole point is that the Luddites have been miscast as anti-technology and anti-progress. The Luddites did not reject technology; they were a labor movement, making pragmatic demands about how the benefits from new technologies would be apportioned.

We should all be Luddites today — not because technology needs to be “decelerated” (whatever the hell that even means), but because we have learned by now what happens when we trust a16z-types to make all the decisions, and we recognize that we deserve much better than that.

Andreessen's manifesto ultimately proves just how small of a man he is. You can't claim the mantle of Bayesian rationalism without learning a single thing from the failures of your own dominant philosophy over the past 30 years. If unchecked markets worked as well as Andreessen insists, we wouldn't be in this mess. The most powerful people in the world are technological optimists. They asked for our trust in the 90s, the 00s, and the 10s. They insisted that all we needed to do was clap louder. We clapped. They failed. We grew less trustful.

In a bizarre way, Andreessen has done me a huge, unintentional favor here. One of the challenges I have been facing with writing my “history of the digital future” book is the “so what” question. Specifically: “Okay Dave, so Louis Rossetto and George Gilder wielded a lot of influence in 1994 and, in retrospect, no one should’ve taken those guys seriously. But it has been thirty years. Is it really worth our time to revisit and tear down these sad, mostly forgotten figures?” Andreessen has supplied me with a ready answer: yes. We ought to pay attention to those confident, faded predictions of decades’ past, because the ideology still suffuses the beliefs and behaviors of today’s tech billionaire-class.

But it's also an alarming essay, specifically because of how much wealth and power Andreessen and his peers have amassed. We don't need cowboy billionaires talking themselves into Leroy Jenkins'ing the climate crisis.

It is a good thing that, after 30 years, we have grown a few critical calluses and no longer reflexively cheer every announcement from the tech barons.

It is a good thing that people are questioning the childlike assumptions of the financial services industry.

It is a good thing that we have grown alarmed enough to organize, that 2023 has been a year of labor victories, that citizens and regulators and elected officials have decided that we all have a larger role to play than as adoring audience of the tech elites’ fantasy tales.

I invite everyone to join us in techno-pragmatism. Whether you are optimistic or pessimistic really doesn’t matter. The water is warm. Become our allies in answering the hard questions and influencing not just the pace, but also the direction of technological change.

Terrific takedown.

I don't know which claim was most absurd, but my 2 favorites were

1) "markets prevent monpolies", almost comical in its proven failure, and

2) those in "ivory towers...are disconnected from the real world, delusional, unelected, and unaccoubtable".

Talk about a self-confession.

Thanks for this thoughtful and incisive critique of techno-optimism. I, for one, would be very curious to hear Andreesen's response to the issues that you raise. Sadly, I doubt Andreesen will ever read your critique, let alone engage with it.

And that's the problem, isn't it? If the 21st Century tech industry has taught us anything, it is that becoming a billionaire is corrosive to a person's intellect. It makes its victims, not stupid, but lazy. Being a billionaire means never having to hear an opinion you don't want to hear, and never having to take "no" for an answer. It's becoming increasingly clear that very few people are able to thrive in such an intellectually sterile environment.

As a young technologist you need cooperation from others, so you are obligated to justify your ideas and sharpen them in response to criticism. You are perforce part of a community of minds that is greater than any single mind within it. All of that give and take, however, is hard work. Once you don't have to do it anymore, it's tempting to skip the hard part and voluntarily cut yourself off from the community. That's when the laziness sets in. Your ideas never improve beyond their first iteration; you never "update your priors," and you are diminished because of it.