That old WIRED ideology

Find yourself someone who looks at you the way 90s WIRED looked at telecom execs.

Part of what I want to do with my next book project is offer a thorough illustration of the ideological project of Silicon Valley tech circles. I think we should be critical of this project, and I think a strong basis for that criticism is to look at its track record. Digital Futurism isn’t just about the future. It’s also about the present, and it now has a substantial past.

Here’s an example that I’ve been thinking a lot about now. Think of this as a bit of early writing on ideas that will someday be book-shaped.

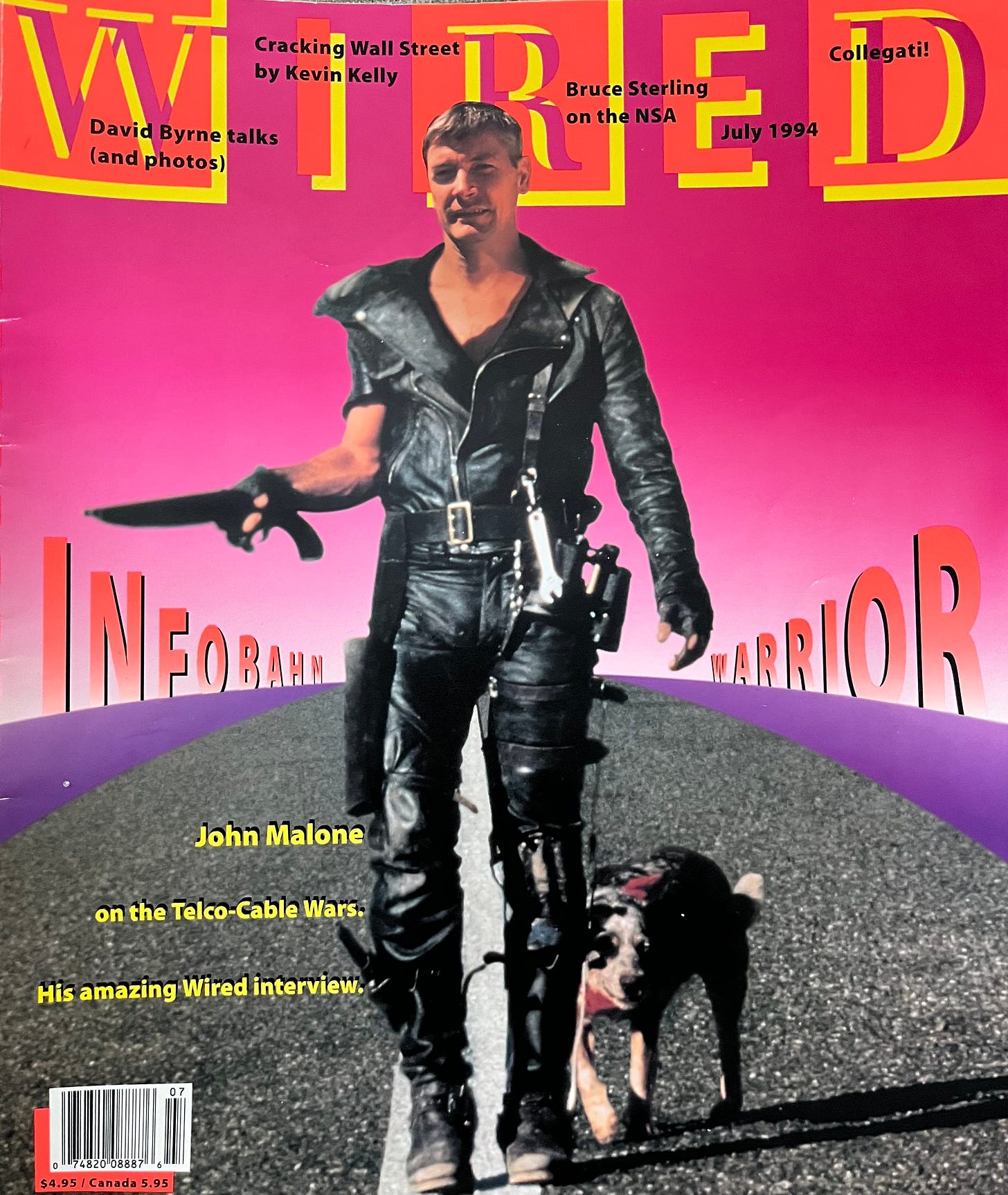

Meet John Malone, circa 1994.

Malone is CEO of cable TV giant Telecommunications International (TCI). The big telecom news in 1994 is that the planned $33 billion merger between TCI and Bell Atlantic has fallen apart. Malone sits down with WIRED’s David Kline for an interview, two weeks after the deal is called off.

Here’s how the magazine portrays Malone:

The interview is, shall we say, remarkably friendly. Most 90s-era WIRED interviews are. WIRED is in the business of covering the heroic engineers, entrepreneurs, and investors who are creating the digital revolution.

(As Founding Editor Louis Rossetto put it in the original “WIRED manifesto," “There are a lot of magazines about technology. WIRED is not one of them. WIRED is about the most powerful people on the planet today—the Digital Generation. These are the people who not only foresaw how the merger of computers, telecommunications, and the media is transforming life at the cusp of the new millennium, they are making it happen.”)

David Kline begins the interview by asking Malone to “explain what really happened with the Bell Atlantic deal.” His basic answer is that meddling government regulators got in the way, and prevented businessmen from doing what businessmen do best! Having established a good rapport by inviting Malone to frame the failure in the best possible light, Klein then invites Malone to offer his sage insights on the state of the information highway (no one else but cable CEOs like Malone can properly build it), Bell Atlantic CEO Ray Smith (“I got a lot of respect for him. He was absolutely a visionary. It’s just that his organization wasn’t willing to go along.”), and the Federal Communications Commission (“Hopefully government will finally realize they’ve gone too far.”)

The interview ends with a flourish from Malone. He promises that the cable industry will build the mass consumer internet by 1996 if someone in the government will provide a little help, by shooting (FCC chairman) Reed Hundt! (Kline responds with a comment instead of a question: “For the record, maybe you should say you are kidding.” Real hard-hitting journalism here, folks. Textbook interview technique.)

Malone, in WIRED’s rendering, comes across as a badass. He’s making moves, taking no prisoners, building the future, and ready to come after the government regulators with guns (literally) blazing.

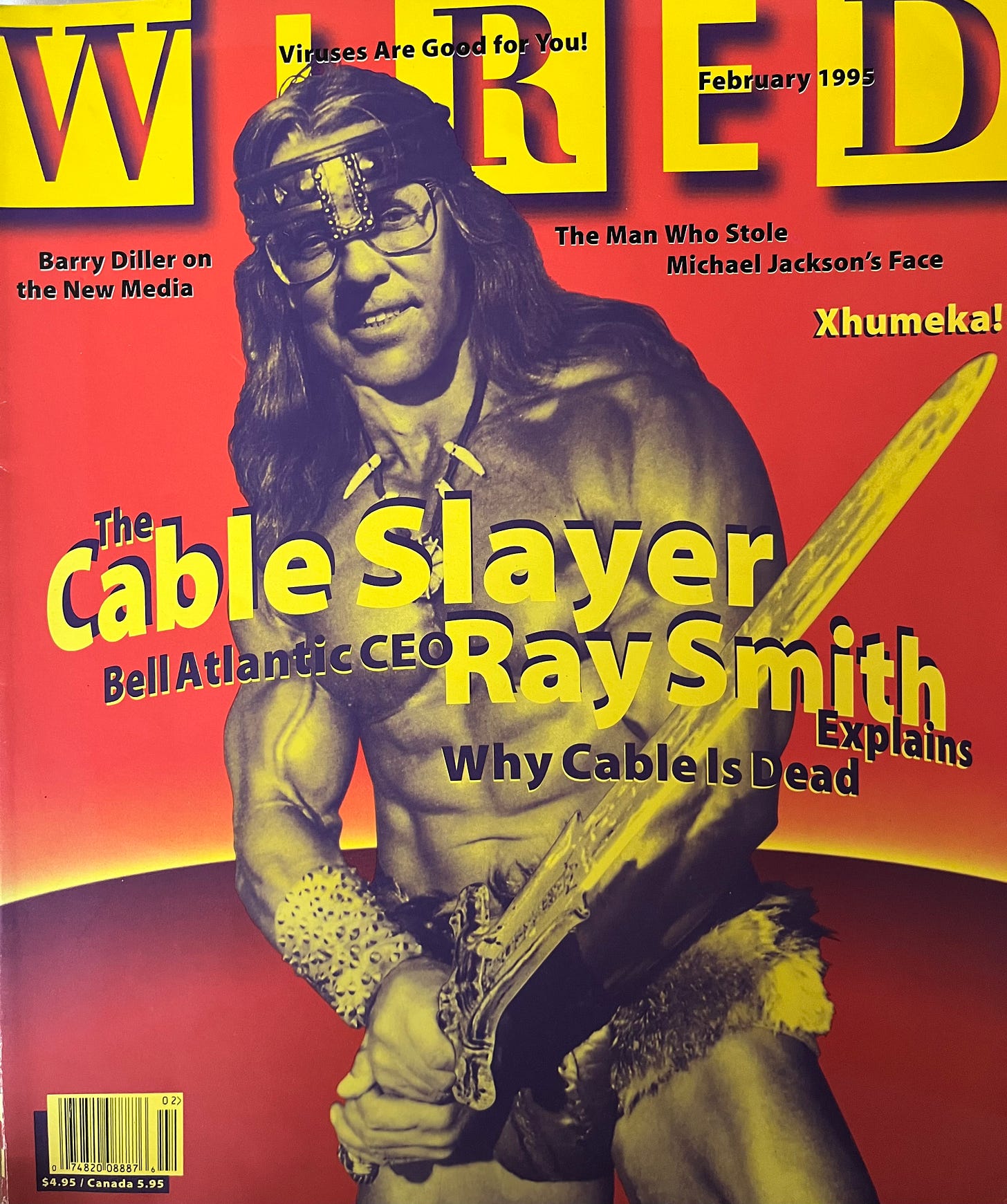

Now meet Ray Smith, Bell Atlantic’s CEO, the man on the other side of the failed merger. Smith, like Malone, receives a nice cover page glow-up. Where Malone is cast as Mad Max, Smith is transformed into Conan the Barbarian:

Smith, we are told in the interview introduction, is “clearly the most enterprising and far-sighted of the telco leaders, (…) the first to begin shifting his once-stodgy utility to a more entrepreneurial footing.” He begins the interview with a visual gag about being a monopolist and “selling Pennsylvania.” Kline plays right along, using it to establish the CEO’s wit and humor for the reader.

Smith offers an alternate explanation of why the deal collapsed: The deal was on strong footing until John Malone made some, uh, unstrategic statements about cutting future dividends. The company’s stock dropped five points and Bell Atlantic’s shareholders came out in opposition to the merger. Malone also ran into cash flow problems after the FCC rolled back cable rates by seven percent. The merger fell apart because it stopped making financial sense for both companies.

John Malone and Ray Smith are friends, and Smith clearly doesn’t want to hang his buddy out to dry in front of the press. Kline has no intention of asking a tough follow-up or heightening the conflict between them. The interview questions are a series of gentle, rolling hills. “What’s your strongest memory of that last meeting [with Kline, before they announced the merger was off]?” “You guys really like each other.” “What if Malone reads this in Wired and calls you up and says, ‘OK, Ray, you're on!"

The interview presents Smith as a titan of industry, offering wise insights about the future of telecommunications to the WIRED’s tuned-in readership.

This is emblematic of the magazine’s editorial position in those early years. Interview subjects were thought-leaders, engineers, and businessmen at the front lines of the digital revolution. These were people who, in the editorial team’s estimation, didn’t receive nearly enough attention or public admiration. WIRED was a friendly venue for the people it covered. (When you hear tech CEOs and VCs complaining today about all the unfair, critical coverage they receive from the tech press, this is the context. They would like to still be treated like innovator-capitalist royalty, like in the good old days.)

There are rare exceptions, though. Meet Reed Hundt, the aforementioned Federal Communications Commissioner who John Malone wanted to shoot.

In October 1994, WIRED’s John Heilemann interviewed Hundt. He receives no glow-up or cover page, instead he’s photographed in suit-and-tie, with a facial expression that reminds me of Jim Halpert’s expressive shrug.

Heilemann’s first question: “Why are you so unpopular?” His second question: “[Malone] says that in ordering the 7 percent solution, you were sort of a dupe to Rep. Ed Markey [D-Massachusetts] - a naive regulator trying to get in good with a key congressional figure. Is that a fair assessment?” Later Heilemann asks, “Which barriers between industries should we remove, and when? (…) Is the Thatcherite vision of deregulation too radical for America?”

Hundt isn’t part of the “Digital Generation” that early WIRED is here to amplify and celebrate. He comes from the government, so the interview proceeds as though he is likely up to no good.

After the interview is published, Hundt takes the unusual step of writing a Letter-to-the-Editor. WIRED had included several of Malone’s accusations as statements-of-fact in the introduction of the piece, and Hundt felt the need to defend himself.

This trio of interviews is, I think, a useful indicator of the magazine’s ideological position. Cable and telecom CEOs are conquering heroes, gladiators in the high-stakes battle over the digital frontier. Regulators are villains or buffoons, standing in the way of righteous progress.

At no point does WIRED consider the possibility that reducing cable bills might be good for consumers. Reading the interviews today, I was taken aback by a passage in the Ray Smith interview, where he is discussing competition between telecom and cable and mentions “Philadelphia, for example, is served by maybe 10 or 11 cable companies. Even inside the city there are four different cable companies. Four!” Smith’s point is that there is that cable is just, by nature, a fragmented and competitive business.

I lived in Philadelphia from 2003-2008. Philadelphia, a decade after this interview. By that time, was a Comcast city. There was no competition. You paid whatever Comcast felt like charging for cable. Comcast installed your cable when and if Comcast felt like installing your cable. If your service was on the fritz, you begged Comcast for help. (I am still waiting on a Comcast technician circa 2007 to arrive.) Cable is a set of regional monopolies. Susan Crawford wrote a whole book on the topic. It is excellent. The only thing undermining the dominance of the cable industry today is cord-cutting.

WIRED’s editors circa 1994 can’t know that cable will be an almost-universally-despised monopoly within a decade. But it also isn’t a possibility that crosses their minds. What’s good for TCI and Bell Atlantic is, in the magazine’s view, good for America. The magazine has a distinct outlook on who the protagonists and antagonists of the digital revolution are, and you can see that in how they portray their interview subjects.

Early WIRED was a focal point for 90s tech culture. It was a deeply ideological magazine. That ideology has been variously described by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron as “The Californian Ideology,” (a “contradictory mix of technological determinism and libertarian individualism [that] would become the hybrid orthodoxy of the information age.”) and by Evgeny Morozov as “Technological Solutionism.” I think both of these descriptions are right, but I also think they are worth expanding upon.

What we can see in the above example is the boundaries being drawn around the heroes, villains, and bystanders of the “digital revolution” as it was understood in the 1990s. Engineers, entrepreneurs, and Silicon Valley investors are the heroes of the story, the motive force driving an inflection point in the course of history itself. CEOs, in this capacity, are the greatest of the bunch. What profession could be more significant than a telecom CEO after all? Governments and regulators, by contrast, are rendered as hurdles to be overcome, or as villains to be surpassed through wit and ingenuity.

This is just one of the key elements of that old WIRED ideology. I’ve written elsewhere about their faith in technological acceleration — a particular, potent strain of tech determinism that insists (because of Moore’s Law) that the pace of innovation is continuously accelerated. I’ll be writing soon about another ideological theme — how technological optimism is a fundamental precondition of their worldview, rather than a byproduct. This optimism obscures at least as much as it reveals, pointing attention away from hard, pragmatic challenges and toward the endless bounty that awaits us in a future of abundance.

I think all this history is especially relevant today because, as the saying goes, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme.” The old WIRED ideology isn’t all that different from the ideology of Sam Altman and Elon Musk and Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen today. Just last year, Altman (The CEO of OpenAI) wrote:

The old WIRED ideology no longer drives present-day WIRED’s coverage. And our present-day tech barons are furious at this betrayal. Andreessen, Musk, and Thiel have each declared their own personal wars against the press. Regulators like Lina Khan are treated seriously by outlets like WIRED. Reporters no longer are quite so fawning in their coverage of the tech/telecom/media CEO-class.

But if tech media has turned more critical, the stakes have also gotten much higher. WIRED in 1995 was a cultural vanguard. But that’s all it was — just one cultural vanguard, among many. Silicon Valley had the aura of futurism, the vague sense that the future was being built there, that they were building something special that the rest of us couldn’t yet quite glimpse. But if tech was a big part of the imagined future, it was still a niche player in the present, with only a scant footprint in our shared historical memory.

Today, we are in many ways living in the tech barons’ empire. They are the richest and arguably the most powerful people on the planet. We have to take their ideas seriously, even the ridiculous ones, because of the sheer amount of capital they have at their disposal. (Once again, MY KINGDOM for a wealth tax!)

The ideological project of today’s tech barons is little different from the ideological project of WIRED’s tech accelerationist, tech optimist, tech solutionist libertarian past. They still wish to be viewed as conquering heroes, gladiatorial competitors jostling for control over the future that only they can build. They still treat public policy and regulation as at best an impediment, and at worst a villain that ought to be swiftly and violently dispatched.

Looking back through old magazines, one can see how poorly these tropes have aged. John Malone was no road warrior. Ray Smith was no gladiator. Reed Hundt was no overreaching government agent.

What was ridiculous in retrospect ought, I hope, to inspire a bit more skepticism when evaluating thee present-day claims of similar ideologues. We should distrust the self-assured bluster of the tech barons and their promoters.

Their confident projections into a future only they can create are no more trustworthy than the unchallenged musings of those who came before them.

Would it be possible to add descriptors to your pictures or web links to pictures in your email newsletters? I read them using simple html view and there are just big, empty gaps where the pictures were.

Thank you!

I remember when Wired first came out in the 90s. I got a free copy, so I read it. I got the impression it was a fanzine, kind of like Tiger Beat, except for technology hot shots rather than cute teen bands. For some reason, I got the impression it was aimed at white boys even though I myself am white. I also read Technology Review, mainly for alumni news and nuts and bolts stuff, and it has a similar uncritical view of technology but a much better excuse being an alumni magazine.