Let's tap the brakes on this A.I. hype-train.

Sam Altman's "Moore's Law for Everything" manifesto is a mess. Why do we still take these people seriously?

Kevin Roose has a piece in the New York Times today, titled “We Need to Talk about How Good A.I. Is Getting.”

So, okay. Let’s talk about it.

The discourse around A.I. has gotten a little out of hand in the past few months. Ever since OpenAI released their Dall-E 2 image generator, it seems like tech journalists have become convinced that The Future is about to arrive.

It’s true that breakthroughs really are happening with Large Language Models (LLMs) right now. OpenAI and its competitors are hurtling through achievement benchmarks that seemed unreachable just a few years ago. Where skeptics like me look at Web3 and the Metaverse and (rightly) say “this is just marketing hype. We’re still years away from anything real,” the A.I. companies have some actual stuff that they can actually point to.

But we should also take the limitations seriously. OpenAI’s marketing operation is even more sophisticated than its neural nets. And they are asking us to ignore plenty of cases where A.I. is still a complete trainwreck. Early in the pandemic, many A.I. experts confidently predicted neural nets had a reached a level of sophistication where they could play a major role in helping diagnose and treat COVID. They were disastrously wrong. As technically impressive as GPT-3 and Dall-E 2 are, GPT-3 has been breathlessly hype for two years and, thus far, its sole use-case is as fodder for think-pieces about just how remarkable GPT-3 is.

But I don’t want to focus on technical developments in machine learning. There are plenty of people who are far better suited to that conversation. (Kate Crawford’s book, Atlas of A.I. is a must-read. Timnit Gebru, Margaret Mitchell, and their coauthors are advancing deep technical arguments about the limits of these systems. You should follow them if you aren’t already.)

Instead, I want to take a look at the ideological claims, assumptions, and ambitions of the people who are promoting these breakthrough technologies. Because the more I listen to them, the more I recognize a set of rhetorical tropes that have been repeated throughout the history of the modern internet.

Back in March 2021, OpenAI’s President, Sam Altman, wrote a manifesto of sorts. It’s a doozy. And I don’t think it’s every been properly stress-tested.

It’s titled “Moore’s Law for Everything.” And it’s a doozy.

Altman is an interesting character. His biography reads like it was ripped from the HBO series Silicon Valley. He attended Stanford for a couple years, just long enough to credibly drop out. He launched a start-up and entered Y Combinator. His start-up failed, but he somehow parlayed that failure into becoming Y Combinator’s new President. In a fawning 2016 New Yorker profile, he is described as a sort of “start-up Yoda.” If Silicon Valley’s VC-class were a religious order, he would be one of its high priests. He isn’t the wealthiest of them all, but he might be the most fervent believer in its teachings.

And this deep and abiding faith — in tech accelerationism, in a near-term future transformed by economic abundance, in the inevitability of technological progress, in the power of disruptive technologies — courses through Moore’s Law for Everything. It is a document that declares “The A.I. revolution is nigh!”, insists it will Change Everything, and calls on us to imagine how we will deal with the most radical social changes in human history once they arrive.

And for such an ambitious argument, from such an important figure in tech circles, it is surprisingly sloppy.

Altman anchors his argument in a deep and abiding faith in Moore’s Law — Gordon Moore’s 1965 prediction that the number of transistors you could fit on a silicon chip would double roughly every two years, while the price of those chips would be cut in half at the same rate. Moore’s prediction meant computers would get smaller, cheaper, and more powerful. It turned out to be eerily prescient. The tech booms of the past fifty years – from mainframe computing to personal computers to the internet, World Wide Web, laptops, cell phones, smartphones, tablets, and the Internet of Things – all have Moore’s Law in common.

In What the Dormouse Said, John Markoff described Moore’s Law as “Silicon Valley’s defining principle. … [Moore’s Law] dictated that nothing stays the same for more than a moment; no technology is safe from its successor; costs fall and computing power increases not at a constant rate but exponentially: If you’re not running on what became known as “Internet time,” you’re falling behind.” It is, in other words, both a technical prediction about processor capacity and a deeply-held cultural belief about the pace of the digital revolution.

It manifests as technological accelerationism — the belief that the pace of technological change is continually speeding up. Technological accelerationists view Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurs, engineers, and investors as the main driver of societal change. They think we are at a hinge-point in human history, and that government legislators, regulators, journalists, and incumbent industries/institutions are at best hapless bystanders and at worst active impediments to the project of building the future.

As a technical phenomenon, processor speed no longer increases at Moore’s predicted rate. Barring further major breakthroughs in the mass production of quantum computing, we are living in a post-Moore’s Law world. The major advances in A.I. have instead relied on changes in chip architecture, rather than processor capacity (Turns out it’s all about the video cards). But the cultural faith in Moore’s Law continues unabated.

What would Silicon Valley be, after all, without this defining principle? If Moore’s Law truly died for good, it turns out the technorati would just carry on, Weekend at Bernie’s-style, pretending it was still with us.

In Moore’s Law for Everything, Altman begins by declaring that, as CEO of OpenAI, he has special knowledge of how close we are to a “tectonic shift” in human society.

In the next five years, computer programs that can think will read legal documents and give medical advice. In the next decade, they will do assembly-line work and maybe even become companions. And in the decades after that, they will do almost everything, including making new scientific discoveries that will expand our concept of “everything.”

This technological revolution is unstoppable. […]

Altman is talking here not just about Dall-E 2 and GPT-3. He’s talking about Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). If you read the literature on this topic, many researchers are extremely skeptical of AGI. It is either decades away or outright impossible. Altman, (whose primary skill set is dispensing start-up wisdom, investing early in other peoples’ companies, and garnering positive press coverage that raises the value of the companies he invests in) is convinced that he knows something these research scientists don’t. The revolution is coming. Altman can see it.

Altman proclaims that the coming Artificial Intelligence revolution is “unstoppable,” part and parcel of the long arc of tech acceleration that we are living through. He writes:

On a zoomed-out time scale, technological progress follows an exponential curve. Compare how the world looked 15 years ago (no smartphones, really), 150 years ago (no combustion engine, no home electricity), 1,500 years ago (no industrial machines), and 15,000 years ago (no agriculture).

And here that we ought to pause and take a deep breath. Because Altman is engaged in some rhetorical sleight-of-hand. Why fifteen years ago? Why not ten?

The answer, I suspect, is that he’s trying to avoid drawing attention to the slowdown of Internet Time. If we focus on 15 years ago, then Altman can make the point that there were “no smartphones, really.” But what about a decade ago?

When I was conducting the original archival study of/for WIRED magazine in 2018, this was the biggest insight I took away from the project. The pace of Internet Time was undeniably fast in the 1990s and 2000s. But beginning around 2010, it has dramatically slowed.

Here’s a refresher on digital life in 2011, based on the cover stories in WIRED magazine that year. Headlines included: “Artificial Intelligence is here. But it’s nothing like we expect.” “The underworld exposed: A guided tour of the dark side [of the internet].” “1 Million Workers. 90 Million iPhones. 17 Suicides. This is where your gadgets come from. Should you care?” “How the Internet Saved Comedy.” “Reverse Evolution: Scientists know how to turn a chicken into a dinosaur. What could possibly go wrong?” and “Why Jeff Bezos Owns the Internet.”

The Internet of 2011, in other words, was an Internet of iPhones and Amazon, of Twitter and Facebook and Google and YouTube. It had a dark underbelly, but it was also great for entertainment. Scientific breakthroughs in Artificial Intelligence and genetic engineering were just on the horizon. It was also an Internet rife with digital surveillance — both by companies (which we knew about and collectively didn’t care) and by governments (which we knew less about, but collectively didn’t much care).

What has actually changed from 2011 to 2021? Instagram and WhatsApp were hot young companies that Facebook had not yet acquired. Uber and AirBnB were still in their early phases – they had not yet become synonymous with the promise of the Sharing Economy, nor revealed as engines of the exploitative Gig Economy. Both made a ton of money for their VC investors without demonstrating that they could turn a reliable profit. This is a story of general stability, not technological change at a gut-wrenching pace.

What else has changed in the past decade? Netflix ushered in a new golden age of television (which lasted until… just a few months ago?) Apple has made smoother and smoother versions of the same products — plus the Apple Watch, which has turned out to be not much of a revolution after all. Google tried to usher in the era of wearable tech with Google Glass. That failed spectacularly. 3D printing was going to change everything. It hasn’t… at least not yet. Oculus Rift was finally going to deliver on the promise of the Virtual Reality revolution. (The Metaverse is still not going great.) Facebook went public, got serious about monetizing all that data it was gathering on everyone. The techlash years happened — big tech stopped being credited for inventing the future and started being blamed for inventing so much of the present.

For two decades, the culture of Moore’s Law really did seem to have ripple effects on the rest of the world. The Internet was constantly changing, evolving, and reshaping our lives at a breakneck pace. Moore’s Law had spilled over — it no longer referred solely to the number of transistors you could fit onto a chip. It was reshaping the economy, media, dating, science, and politics.

But Moore’s Law has faded. Technology companies aren’t reinventing the world anymore. They are just acquiring control and extracting revenues from larger and larger portions of it.

If Altman focused on the past decade instead of anchoring his history to Steve Jobs introducing the iPhone, then the slowdown of Internet time would be more obvious. That would be a problem for the story he wants to tell. It would leave his readers wondering just how all-encompassing this A.I. revolution is going to be. It would leave us thinking about all the other promised technological revolutions of the past decade that have turned out to be permanently delayed. We might think about the limitations, and about setting reasonable boundaries on OpenAI’s products, instead of gaping in awe at the inevitable technological change arriving before us.

Once you start reading Altman’s manifesto with a more suspicious eye, some other glaring mistakes rise immediately to the surface.

Altman lists four industries that he expects will soon be completely upended by Artificial Intelligence: housing, health care, education, and lawyers. He picks these not because they are particularly vulnerable to replacement by machine learning, but because they are particularly expensive.

Here’s Altman’s explanation for why the A.I. revolution is about to transform these industries:

AI will lower the cost of goods and services, because labor is the driving cost at many levels of the supply chain. If robots can build a house on land you already own from natural resources mined and refined onsite, using solar power, the cost of building that house is close to the cost to rent the robots. And if those robots are made by other robots, the cost to rent them will be much less than it was when humans made them.

Similarly, we can imagine AI doctors that can diagnose health problems better than any human, and AI teachers that can diagnose and explain exactly what a student doesn’t understand.

I don’t have deep subject-matter expertise in housing or medicine. But neither does Sam Altman. What immediately stands out to me here is that labor is not the driving cost of the housing, healthcare, or higher education markets!

The real estate market has not gotten phenomenally expensive in major cities because it costs too much to build additional housing. It has gotten phenomenally expensive because of a mix of bad regulations (zoning rules), bad market forces (AirBnB turning potential homes into permanent “short-term rentals”), and soaring wealth inequality (rich people buying all the properties as “investments” like it’s a monopoly board). Artificial Intelligence solves none of those problems. It will likely make the latter two much worse by helping unconstrained rich people find new ways to increase their wealth and power while sidestepping existing regulations.

And sure, we can imagine A.I. doctors that can diagnose health problems, and perfect A.I. teachers. But this is just lazy sci-fi noodling. Hell, we’ve been imagining that for at least two decades. That was Jim Clark’s big idea with Healtheon. As Michael Lewis documents in his book about Clark, The New New Thing, Clark wanted to revolutionize the American health care market without bothering to learn much of anything about the American health care market. He just noticed that health care was a multi-trillion dollar sector and decided it was the next thing to disrupt. The company he built is now WebMD. It didn’t disrupt much of anything.

This is a rhetorical trick that the Silicon Valley though-leader class has been pulling for decades. Jim Clark didn’t know shit about health care, but he talked investors into believing the force of Moore’s Law was about to change everything. Sam Altman doesn’t know shit about health care either, but he is convinced we can revolutionize the entire sector without bothering to learn a single thing about the institutional forces that make American health care so stupid-expensive (hint: it ain’t a simple story about doctors’ expensive labor costs!).

Technologists like Altman have also been talking about revolutionizing education for 30+ years. The very first issue of WIRED magazine featured an article discussing how the coming computer revolution would unleash “hyperlearning” and completely change the education system. In the mid-2000s, One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) was the toast of the TED talk circuit. In the 2010s, we had an entire hype bubble surrounding Massively Open Online Courses (MOOCs), with tech visionaries promising the imminent disruption of higher education through free online courseware. OLPC turned out to be an elaborate white-tech-savior exercise. MOOCs turned out to be a trash fire. The costs of higher ed kept rising.

But you know what didn’t increase? Professor salaries. Labor costs are not driving increased tuition payments. Altman is imagining magical AI solutions to problems that he has not bothered to understand or correctly diagnose.

There are other professions that face much more self-evident risk from OpenAI’s suite of A.I. tools. It’s reasonable to expect that GPT-3 will be able to produce replacement-rate marketing materials very soon. OpenAI’s coding tool, Copilot, may soon be able to handle a ton of entry-level coding work. It won’t replace all software developers, but it might reduce the overall size of the industry. As Charlie Warzel learned last week, visual artists are already rightly concerned that Dall-E 2 will replace the type of contract work that is one of their few reliable income sources.

But my hunch is that we’re going to spend the next few years incorporating A.I. tools into these existing fields, rather than replacing them outright. Existing institutions will respond and adapt, just like they always do. Rather than rewriting the rules of society, A.I. products will adjust to the formal laws and informal norms that govern society. Societal change will happen at the margins, influenced by active policy decisions (including the decision that would benefit Altman the most — total regulatory inaction. That, too, is a policy choice).

Consider Public Relations as an example. At first glance, it’s easy to look at some GPT-3 text and conclude “yeah, this is a game changer. The whole P.R. industry is toast.” But let’s push a little harder. The single greatest trick the P.R. industry ever pulled was convincing clients it was necessary. This has been the case despite mountains of evidence that the gains from advertising rarely match the costs.

Assume for that moment that, now or very soon, GPT-3 will be able to provide replacement-rate advertising copy at a fraction of existing costs. The next hurdle is this: which mid-level marketing executives will tell their bosses that they only need replacement rate comms? Which executives will tell their boards, or communicate to their shareholders, that they’ve alighted on a great cost-saving maneuver by putting a neural net in charge of the company’s comms work? Change will happen slowly in this industry, because existing institutional arrangements will create friction points that slow it down.

If you believe, as Altman does, that technological change is an inevitable social force, then the answer is “give it time. None of that will matter.” But if you pay attention to the actual history of how technologies have been incorporated into existing industries, you’ll find that (a) nothing is inevitable and (b) existing institutional arrangements always matter.

This isn’t to say that GPT-3 will never become more than a toy. In 20-30 years, I imagine many industries will have incorporated narrow A.I. into their institutional arrangements. But we have a lot of agency in determining how these technologies get incorporated. Assuming inevitability and overestimating the size and speed of the social transformation is a method of handing all decision-control to Sam Altman and his investors.

Back in 1994, John Perry Barlow wrote an article for WIRED titled “The Economy of Ideas.” Barlow was one of the O.G. techno-optimists — a cofounder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the author of the “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” In The Economy of Ideas, he takes an early look at copyright law and speculates on the ways that it is going to run up against the digital revolution.

It’s a really smart piece of writing — one of the best from WIRED’s early years, IMO. There’s one passage that sticks out in my mind, though:

Intellectual property law cannot be patched, retrofitted, or expanded to contain digitized expression any more than real estate law might be revised to cover the allocation of broadcasting spectrum (which, in fact, rather resembles what is being attempted here). We will need to develop an entirely new set of methods as befits this entirely new set of circumstances.

Most of the people who actually create soft property - the programmers, hackers, and Net surfers - already know this. Unfortunately, neither the companies they work for nor the lawyers these companies hire have enough direct experience with nonmaterial goods to understand why they are so problematic. They are proceeding as though the old laws can somehow be made to work, either by grotesque expansion or by force. They are wrong. (emphasis added)

John Perry Barlow, like Sam Altman, was a charismatic tech accelerationist. Unlike Altman, he was more thorough in thinking through how the old social structures would come into conflict with revolutions in communications technology. But he also displayed a confidence that the old institutional rules and designs would eventually bend or break, giving way to the force of technological change. And, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that he was wrong.

Copyright protections and intellectual property law turned out to be a major shaping force in the trajectory of the modern internet. These were maybe the only rules that Silicon Valley companies were not encouraged to break with reckless abandon. So, instead, the tech industry adapted. The immutable force of technological change turned out to have an occasional mute button after all.

I think back to this Barlow passage a lot because, of course, copyright protections and intellectual property law are the Achilles Heel of every one of OpenAI’s products. OpenAI has whistled past questions about the legality of using copyright-protected training data for Copilot. The intellectual property questions surrounding GPT-3 and Dall-E 2 are… unsettled, to say the least. (I am not a lawyer. But I can usually spot the times when lawyers are going to need to weigh in on something.)

If we believe Altman’s argument that the A.I. revolution is an unstoppable force, then it’s easy to conclude that existing copyright and intellectual property regimes will just have to get out of the way and be rethought later. And, once again, that is a very profitable line of reasoning for Altman and his company. But recent history suggests the opposite. It suggests that the techno-accelerationist project is a mix of wishful thinking and motivated reasoning.

Instead of detailing how OpenAI’s products should be designed to improve society/increase prosperity/obey existing laws/avoid social harms, Altman focuses on a broader set of questions about how we reorganize society to take advantage of the abundance and riches that will flow from the A.I. revolution. This, once again, is a rhetorical move with a deep pedigree and a terrible track record.

I wrote about this in my 2018 article, characterizing lessons from the first 25 years of digital history:

LOOKING BACK AT WIRED’s early visions of the digital future, the mistake that seems most glaring is the magazine’s confidence that technology and the economics of abundance would erase social and economic inequality. Both Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 imagined a future that upended traditional economics. We were all going to be millionaires, all going to be creators, all going to be collaborators. But the bright future of abundance has, time and again, been waylaid by the present realities of earnings reports, venture investments, and shareholder capitalism. On its way to the many, the new wealth has consistently been diverted up to the few.

The economics of abundance is a standard trope among visionary techno-optimists. Moore’s Law is always about to erase scarcity and about to unleash the largest social transformations since the discovery of fire. It was part of the deregulatory push in the 1990s. It was part of the Web 2.0 hype bubble in the early 2000s. It has been a feature of basically every big, bold tech prediction.

I have held out hope that, in the aftermath of the techlash years, we might have developed some collective immunity to this particularly rich-dude-fantasy. Seeing how Altman and his friends are being treated credibly as they rehash these old bromides leaves me to wonder if we just lack the willpower or intellectual curiosity to learn from the not-so-distant past.

There’s a passage in Cade Metz’s book, Genius Makers, where he describes Altman as follows: “He, too, was someone who lived as if the future had already arrived. This was the norm among the Silicon Valley elite, who knew, either consciously or unconsciously, that it was the best way of attracting attention, funding, and talent, whether they were inside a large company or launching a small startup.” Metz also makes it clear that Altman’s faith in technological inevitability is strategic. It is both a marketing gimmick and a way to get the most out of people.

It has served Altman well as he has risen through the ranks of the tech elite. I can think of few people who have turned a failed startup into such an illustrious career. But that’s all the more reason that we should discount his grand claims about the inevitability of the A.I. revolution. The benchmark successes of OpenAI (and other companies like Deepmind) are designed to foster a public narrative about the inevitability of accelerating technological transformation.

Maybe this time will be different. But we should still maintain a healthy dose of skepticism.

Let me conclude by returning to Kevin Roose’s piece. Roose has not been completely hoodwinked by Sam Altman’s sales pitch. He has spent the past few months playing around with Open AI’s signature products, and they have impressed him. His ultimate suggestions are all basically right — he wants legislators to get up-to-speed on this stuff, he wants the companies producing these LLMs to be transparent about what they are actually building, and he wants journalists to cover it in clear-eyed, sober terms. I’m on board with all of those ideas.

But I would add a note of caution that we ought to guard against the usual mix of promotional marketing hype and ominous criti-hype (h/t Lee Vinsel, who coined that excellent term). Criti-hype is when critics of an emerging technology accept all the unsupported claims of its promoters in order to convince people it is a very bad thing that must be stopped! (Look back to the Cambridge Analytica saga to find a ton of early criti-hype.)

We can take GPT-3 and Dall-E seriously without uncritically accepting OpenAI’s claims about the speed, scope, or inevitability of the A.I. revolution. We can see rhetorical tropes from Sam Altman that are identical to the claims of past tech evangelists. These are strategic claims, intended to advance an agenda. We should recognize them as such.

So let’s tap the brakes on this A.I. hype-train.

We’ve heard this song before.

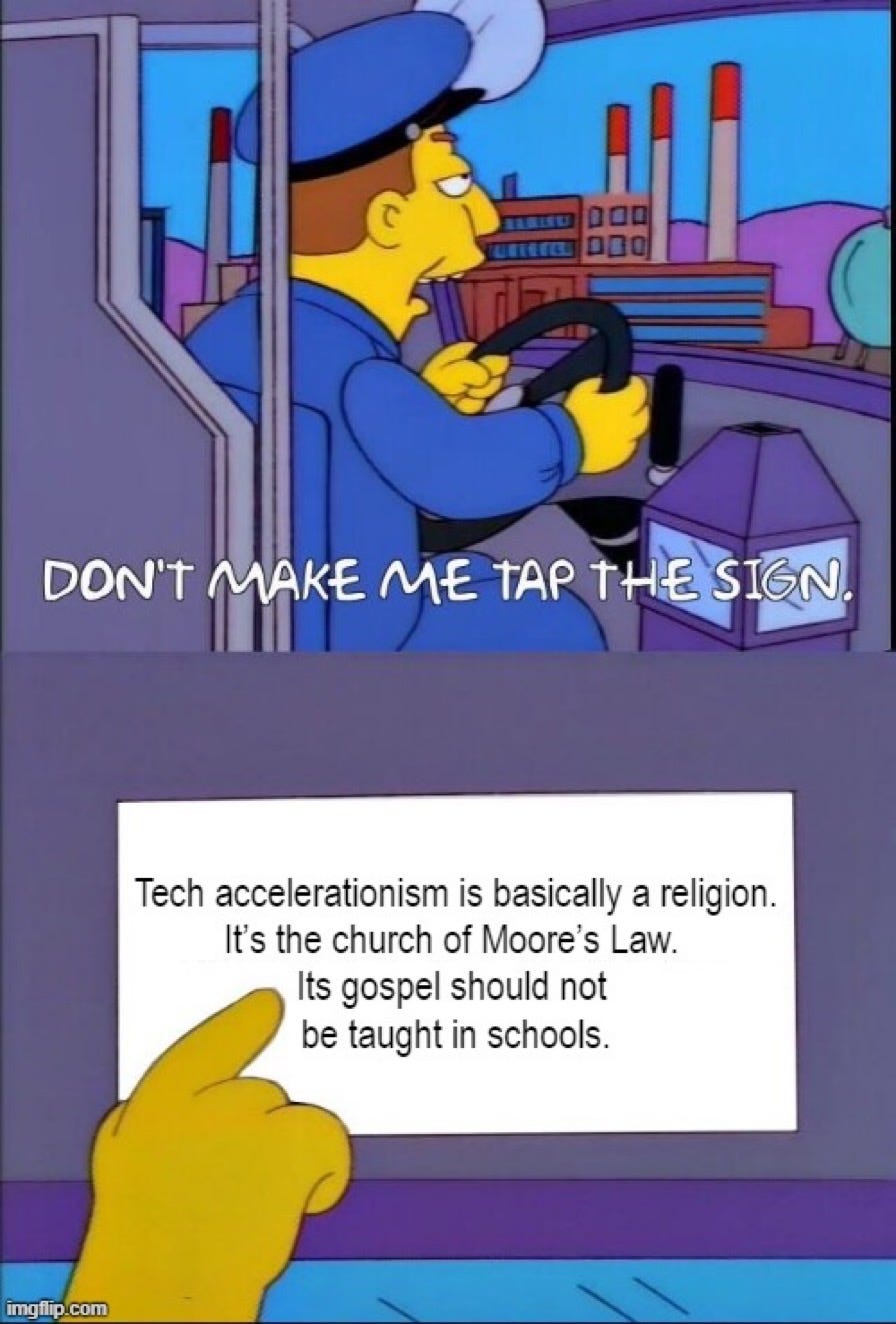

We don’t need to attend services at the Church of Moore’s Law.

We still have plenty of time.

Altman, like every other startup CEO, is first and foremost (and quite often only) a salesman. That alone should tell you how to take his predictions. Like any software salesman, he guarantees the product can do exactly what you say you need. Then he gets his commission and walks away, leaving Customer Support and maintenance releases to clean up the mess. I worked in Silicon Valley for 32 years and watched that particular con up close many times. And yeah, Moore's Law. I worked at a CAE company. Moore's Law is running into a few problems like the speed of light (the clock speeds are getting up there, and those electrons have to obey the law) and the size of molecules (they're using something called 3-D design, where the chip layout looks like rows of skyscrapers, to deal with this). It was a good run, but it turns out, Reality, like Nature, bats last. Moore's Law in its original scope is dead as a doornail. And as you point out, as a metaphor it was always a con.

And good luck slowing down the hype train. That list of recommendations from Roose?

* Legislators up to speed

* Transparent software companies

* Clear-eyed, sober journalists

all good and necessary, and a complete reversal of many decades of trends in every area, let alone AI, born and bred on hype. The whole SV/VC culture is still running on the fumes of its glory days, propped up only by the sheer amount of money sloshing around the top 1% with nowhere to go. A perfect culture for hustlers promising the next PC, the next cell phone, the next killer app. It was always thus, it was just a handful of incredibly lucky and ruthless white guys caught the perfect wave in a small window of time. Now, its like moving to Hollywood in 1965 to be a star.

As a Master Carpenter with over 40 yrs experience, I'm still waiting for the robots to arrive. It turns out that there isn't any robot that can do much constructing a house. Basically we need robots like C3PO in Star Wars, that is a mechanical humanoid. We're no where close to that from what I've read. I heard that they tried to make a brick-laying machine but it didn't work. So Altman is flat out wrong about AI doing much with housing. I think I better retire.

Rush McAllister