Last week in my History of the Digital Future class, I asked my students what they would put in a “reverse time capsule.”

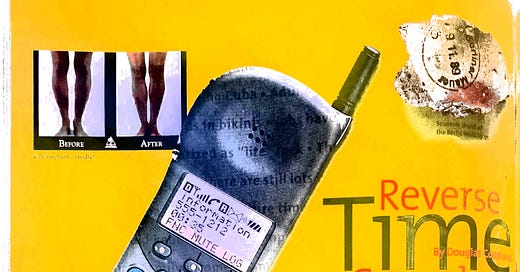

The idea for this activity comes from a 1995 special issue of WIRED magazine. Douglas Coupland asked what artifacts from his day would most surprise the citizens of 1975. True to the technological optimism of the moment, he mostly focused on technological breakthroughs (cell phones! laptops! Portable CD players! Satellite dishes! Remote controlled TVs!), along with the end of the Cold War.

I asked my students to think about what they would put in a 20-year reverse time capsule (2002) and a 10-year reverse time capsule (2012).

One thing I like about this activity is how it helps ground our understanding of digital history. Today’s 20-year-old college students were born in 2001-2002. That means their relationship to the original dotcom boom (Netscape, AOL, dial-up, Windows 95, Geocities, Pets.com, etc) is on par with my relationship to Watergate, disco, and stagflation when I was in college. They are important cultural reference points that shaped the world we inhabit today. They’re formative experiences for an older generation. But they are also decidedly before-my-time.

The other thing I like about the activity is how it brings the slowdown of internet time into stark relief.

Think about the gadgets that you would include in a reverse time capsule to 2002. There’s the iPhone. The iPad or another tablet computer. Maybe a Tesla. You could send them an Apple Watch or an Oculus Quest, but you might want to attach a note explaining how little we have ended up using them.

What about content? Maybe we download Disney+ or Netflix original programming onto the iPad. We could have the iPhone include a demo of the Uber app, or provide a streaming video covering a typical day on Facebook, Youtube, Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.

Send those technologies back to the denizens of 2002 and I think they would be suitably impressed. But send them back to 2012 and I imagine we’d encounter resistance over just how little had actually changed.

The iPhone was the breakthrough technology of 2007. The iPad debuted in 2010. Tesla’s IPO was in 2010 as well. The defining digital technologies of 2022 are all just refined versions of objects that were already part of everyday life in 2012. It isn’t as though big tech has stopped trying to entice us with radical new gadgetry — just in the past decade, we have seen the rise and fall (or at least rise and stall) of Big Data, the Internet of Things, 3D printing, drones-for-everything Google Glass, and virtual reality. We’ve also had a full decade of predictions that driverless cars, artificial intelligence, and the blockchain would disrupt everything in the next six months.

The pace of digital change used to be incredibly fast. For the past decade, it has slowed to a crawl.

The twist, of course, involves the other items the students thought belonged in the reverse time capsule: An N95 mask. The Moderna vaccine, along with a note about all the vaccine misinformation and mass Republican refusal to take the vaccine because Tucker Carlson said it would take their freedom away. A video of Donald Trump’s inauguration speech. The front page of any newspaper from January 7, 2021.

Oddly enough, these political upheavals would seem more believable in 2002 than in 2012. In 2002 the country was still shellshocked from the 9/11 attacks. The Apprentice had not aired yet, so Donald Trump was still that real estate developer from the tabloids. You can pack an awful lot of uncertainty into twenty years.

I remember 2012 quite well. (Hell, that was the year I started teaching at GWU. …The trouble with teaching college students is I keep getting older, they stay the same age.) The Tea Party was ascendent in Republic politics. Mitt Romney seemed like an appropriate standard-bearer for the extremist, anti-tax, anti-government, anti-everything Republican Party. The country was polarized, the government dysfunctional. The stock market had recovered from the 2008 crash, but the economy hadn’t. Occupy Wall Street had put a spotlight on economic inequality and our two-tiered system of justice.

And yet amidst all those fundamental problems, there is simply no chance that 33-year-old-me would believe that the Republican Party nominated Donald J. Trump, or that he managed to win the Presidency, or that his supporters staged an insurrection after he failed to be reelected, or that the entire Republican Party leadership then memory-holed all evidence of the attempted coup.

I also would have had trouble believing that a pandemic that claimed the lives of 852,000 Americans would seamlessly transition into the new front lines of the culture war. The country unified after 9/11. The country unifies in the aftermath of a major natural disaster. Certainly something this big would provoke at least a temporary shift. I’m not, by nature, a particularly optimistic fellow. But viruses don’t recognize party identification, and Republicans never blinked at the measles or polio vaccine. I would not have believed in 2012 that even a virus like this would become grist for the conservative fear-and-misinformation machine.

I teach one other course this semester — Strategic Political Communication. I’ve taught this class nearly every semester for the past decade at GWU. It builds on many of the concepts and models that I’ve taught since my Sierra Student Coalition days.

Strategic Political Communication is designed to be timely and practical. It teaches students to look at the world around them, identify leverage points, and design campaign interventions that can change things for the better.

I’ve only taught History of the Digital Future for three years. It is designed to be a guided tour through the archives of WIRED magazine. It’s meant to be goofy fun. The students learn a ton, but it isn’t meant to have anything to do with breaking news. (One of the nice things about studying history is that it doesn’t change.)

It strikes me this semester that something in the DNA of the two classes has been inverted. History of the Digital Future is almost too timely. Want to understand NFTs, or Web 3, or the Metaverse? This class will help. Want to understand how we arrived at a gig economy and an information environment run through a handful of massive, barely regulated companies. Yep, we cover that too. The class helps students fine-tune their tech bullshit-meters. In the past six months, that has become an increasingly relevant skill.

Strategic Political Communication, meanwhile, feels jarringly stuck. The class teaches students what political communicators can and cannot realistically accomplish. At the national level, we are now in a strategic environment where (1) nothing gets accomplished unless the Senate changes its filibuster rules, (2) Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema won’t change the filibuster rules, and (3) the Supreme Court is filled with conservative ideologues who will abandon all precedent to overturn any administrative rulemaking that displeases them. There is also every reason to fear that January 6, 2021 is only a precursor to January 6, 2025. We may very well have three remaining years left on the clock for American democracy, and they are being whittled away in a manner that is as structurally predictable as it is existentially frustrating. The central lesson my Strategic Political Communication students take away from class these days is “Oh. Great. It’s even worse than I thought.”

Political time is supposed to be slow. The arc of history bends, we hope, toward justice, but it is a long arc indeed.

Internet time is supposed to be fast. (Or at least, that’s the bedrock cultural assumption imparted by Moore’s Law.)

As I begin another semester in the classroom, I can’t shake the sense that the two have gotten reversed.

Over the next few months, I’ll be using this substack to elaborate on the causes, consequences, and implications of both.

A cultural reverse time capsule:

Chopped and screwed to the left of me,

Hyperpop to the right,

Here we are. There is no escape.