Let’s dip back into the pages of 90s-era WIRED magazine. There are a pair of articles that illustrate who the old WIRED ideology was aligned against . Both stories use grandstanding wagers to make a broader point about the expected trajectory of society.

I’ve written previously about who the heroes were in the 90’s tech optimist narrative. I’ve also written about the continued relevance of the worldview. The magazine is no longer the intensely ideological outfit that it once was, but today’s tech moguls are staunch disciples of its teachings.

So today I want to talk about the people who get framed as villains in this narrative. The villains represented everything that WIRED’s masthead thought was ailing contemporary society. They were worriers, instead of optimists. They believed governments, not entrepreneurial capitalists, ought to be the main arena for sorting through social transformations. Instead of showing faith in the emancipatory potential of Moore’s Law and the gospel of abundance economics, they fretted over the “limits to growth.”

It’s something that has occasionally bogged me down while reading through the WIRED back catalog.

…Because, well, these villains? It turns out they’re people a lot like me.

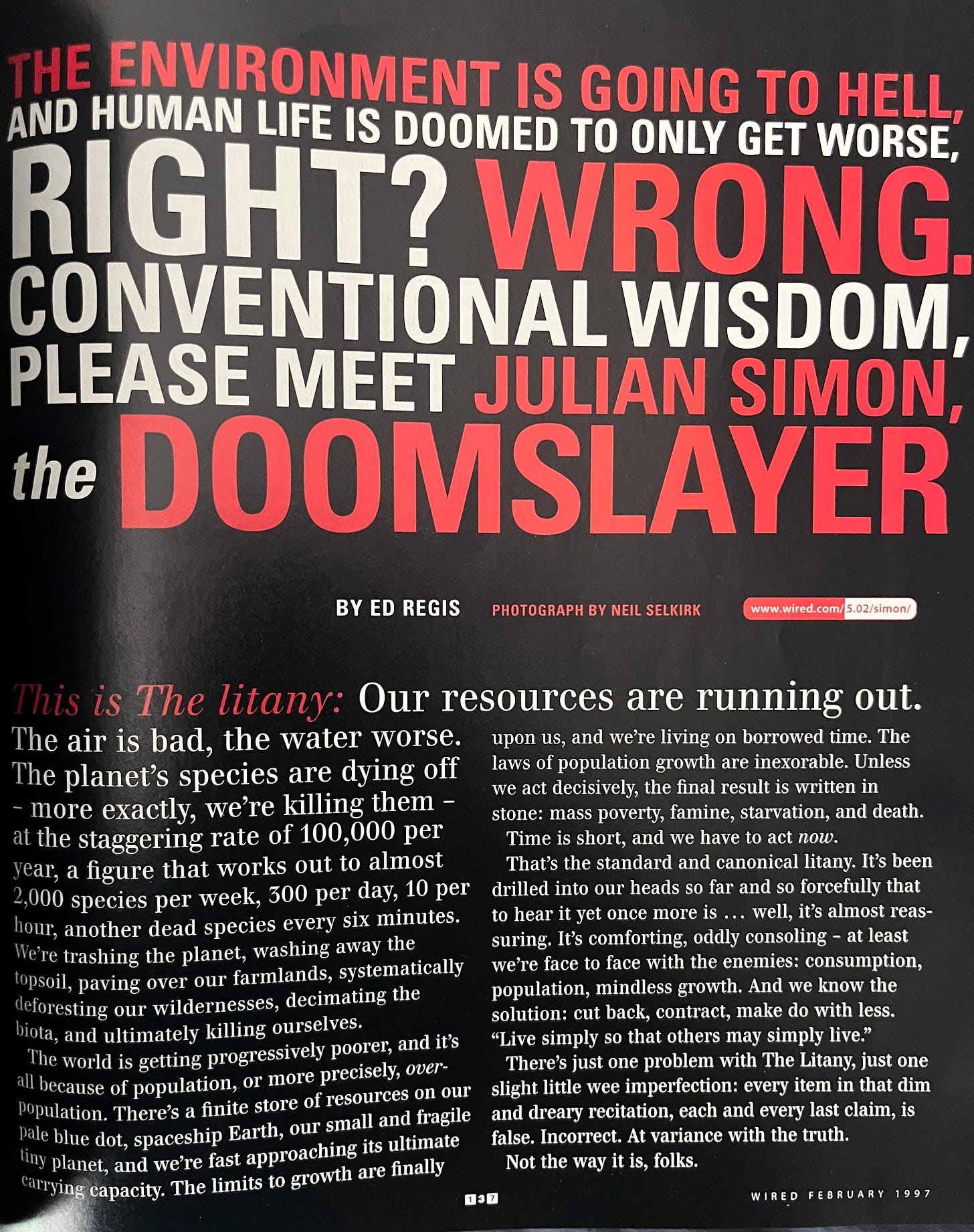

In February 1997, WIRED’s Ed Regis wrote a glowing feature story about business administration professor Julian Simon. Regis renders Simon as a heroic truth-teller, “The Doomslayer,” who stood up to the forces of conventional wisdom, and won.

The article begins with a recitation of what Regis terms “The Litany.”

“Our resources are running out. The air is bad, the water worse. The planet’s species are dying off… We’re trashing the planet, washing away the topsoil, paving over our farmlands… The world is getting progressively poorer… There’s a finite store of resources on our pale blue dot, Spaceship Earth, our small and fragile tiny planet, and we’re fast approaching its ultimate carrying capacity.

[…]

There's just one problem with The Litany, just one slight little wee imperfection: every item in that dim and dreary recitation, each and every last claim, is false. Incorrect. At variance with the truth. Not the way it is, folks.

Such an extraordinary claim ought, you might think, require extraordinary evidence. But it actually based on little more than the $576.07 Simon won in 1990 on a bet with environmentalist Paul Ehrlich. And the details of that bet are just a tad more complicated than WIRED lets on.

This bet is actually the subject of an entire book by historian Paul Sabin, The Bet: Paul Ehrlich, Julian Simon, and Our Gamble over Earth’s Future.

Sabin’s treatment is excellent (I really can’t recommend it enough). Here’s his summary of the bet :

In 1980, the iconoclastic economist Julian Simon challenged celebrity biologist Paul Ehrlich to a bet. Their wager on the future prices of five metals captured the public’s imagination as a test of coming prosperity or doom. Ehrlich, author of the landmark book The Population Bomb, predicted that rising populations would cause overconsumption, resource scarcity, and famine—with apocalyptic consequences for humanity. Simon optimistically countered that human welfare would flourish thanks to flexible markets, technological change, and our collective ingenuity.

You can see here the outlines of a small monetary wager with significant philosophical stakes. The 1970s were the peak years of American environmentalism as a mass movement. The early 1970s were when all of our landmark environmental laws — the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, etc — were passed, and when the EPA was created. And Paul Ehrlich was one of the movement’s leading lights, a regular on the Johnny Carson show and before the halls of Congress. He was known for a charismatic sort of doomsaying — he and his colleagues had developed rudimentary mathematical models that predicted human population growth would devastate the natural world and lead us all into ruin.

Simon, by comparison, was something of an anti-charismatic optimist. He was obsessed with data, but only a very particular sort of data — the type that could be found in official volumes published by the government. He dismissed critics who pointed to sophisticated empirical analysis published in peer-reviewed journals as counter-evidence, insisting their findings did not matter. “There are no other data,” he was fond of saying. If you couldn’t find it in a hefty tome of official factoids, then it wasn’t real. He was, in other words, a libertarian crank with a chip on his shoulder.

But he knew how to pick a good fight.

Paul Ehrlich, circa 1980, was far better-known than Simon. Simon goaded Ehrlich into making the bet. Surely, if the “Limits to Growth” hypothesis was correct, then the prices of our scarce natural resources would skyrocket over the coming decade. Ehrlich, filled with hubris and knowing basically nothing about economics or commodities markets, was confident this was the case. The Ehrlich-Simon bet was memorialized in the pages of Social Science Quarterly on September 29, 1980. The bet was described contemporaneously as “the scholarly wager of the decade.” (Which, uh, sure. Was there even a runner-up in that category?)

Ronald Reagan would be elected President five weeks later. The bet coincided with an inflection point in U.S. politics. Reagan’s election was the moment when U.S. political elites decided the regulatory state was too strong and ought to be deconstructed. We’ll just let markets work their magic and hope for the best.

Simon ultimately won. All five minerals they agreed upon were in the midst of a price spike in 1980. The prices fluctuated over the coming decade, and were below their 1980 peak (adjusted for inflation) in 1990. Simon won a few hundred dollars, and also substantial bragging rights. The bet made him a minor celebrity among critics of environmental regulations, who insisted his victory had proven the entire environmental movement to be little more than fraud. As Sabin puts it:

Ehrlich and Simon’s bet quickly became a symbolic weapon in a long-running ideological battle between conservative critics of regulation and environmentalists. For conservatives and libertarians, Simon’s victory proved that environmentalists were fools.

But Simon’s victory came with a hefty asterisk. He wasn’t arguing “these prices are inflated in 1980, and they’ll come back down in the coming decade.” He was making a much more sweeping claim: that the power of unbridled human ingenuity would make resources more abundant, meaning prices would forever trend down. The future, in his rendering, bends inevitably towards abundance and prosperity (so long as regulators and gloomy critics stay out of the way).

The reality is that Simon’s win was more lucky timing than anything else. A team of economists later ran a simulation to determine, for any 10-year period between 1900 and 2008, which side would have won the bet. Team Ehrlich would have been the winner 63% of the time.

This nuance is completely absent from Regis’s WIRED profile, seven years after the wager had concluded. Regis gives Simon the full hagiographic treatment. He describes Simon, in 1980 as having, “broke out into the light of day, he sprang forth onto the world stage, he started swinging his Diamond-tipped sword - thwick-thwack! - as The Doomslayer!”

(The writing is, well, um, a LOT.)

Nowhere in the piece does Regis (or Simon) allow for the possibility that environmental conditions got better because the environmental regulations did what they were supposed to do.

Consider: The air and water got cleaner in the 1980s and 1990s. The Cuyahoga river stopped routinely catching on fire. The international community learned there was a hole in the ozone layer, and passed a treaty that had the effect of stopping it. This could be treated as evidence that all those pesky environmentalists were panicking over nothing. Or it could be evidence that corporations behave according to their incentives, and regulations can actually work.

(If at time A the alarmists say “there is a threat, we must do XYZ!” and then at time B, the government responds by doing XYZ, and then at time C the threat diminishes, this is not proof that the alarmists were charlatans!)

Simon, in this sense, is a bit like those pundits who spent 2020 insisting we need not worry about all those Republican Secretary of State candidates who were running on a platform that they would overturn the 2024 election if it didn’t go their way. Performatively “centrist” pundits spent months insisting that everyone else was being hysterical, that we need not pay attention to the actual words coming out of the actual mouths of actual candidates who were actually polling within the margin of error. And then, when those candidates had lost, thanks to all of the clear, urgent communications about their anti-democratic stances, the pundits had the temerity to take a victory lap. “See? They lost! It was fine. I told you you were overreacting.”

Just to be clear, Paul Ehrlich is no hero in this story either. Ehrlich and his cohort of doomsaying environmental advocates warned in the 1970s of impending environmental apocalypse. They were sure that our cities would lie in rubble by the 1980s. Many of their predictions proved disastrously wrong. And their predictions regarding overpopulation have been particularly calamitous, tilling the soil of the modern anti-immigration movement.

Ehrlich showed far too much certainty in models that were far too basic to have the sort of predictive power he granted them. (Don’t do that. That never ends well.)

He violated Davies’ Law, showing zero interest in learning much at all from his predictive failures. (Really. Just don’t. If you can’t productively your missed predictions, how will you ever learn anything new?)

He made an exceptionally dumb bet that had little upside for his cause, while elevating his opponent into a sort of folk hero. (Ehrlich went full Balaji in this bet. Never, ever go full Balaji.)

And, as Sabin argues in his book, one direct consequence of Ehrlich’s 1970s-era rhetoric was that people came to distrust the dire warnings of environmental activists and environmental scientists. (Not great. Extremely not great!)

That said, I find it hard to offer a full-throated rejection of his doomsaying publicity strategy. We have to consider the possibility that, without the urgency and certainty and clarity of the movement’s rhetoric in the early 1970s, those landmark environmental laws might not have passed. It would be nice if we lived in a world where more measured, nuanced public communications (ones that don’t play so well on Johnny Carson) would have achieved the same results. But I cannot say with certainty whether we did then, or whether we do now.

Still, that style of brash, confident alarmism has not aged well at all. We live with its legacy today, and it is a tough burden to bear. It had a host of foreseeable-but-unintended consequences. But it may have been the best strategic choice at the time though. I’m just not sure.

But what’s more important for the purpose of this essay is why WIRED, circa 1997, decided to reach back to a 1990 academic bet and canonize Julian Simon as one of their patron saints. Simon was a third-rate business administration professor, furious that the world never hailed him as a first-class economist. He also, ohbytheway, believed that there was an infinite supply of copper because, at the right price point, humankind would just figure out how to transmute copper from other metals. (Sabin, p. 132)

The guy was a crank and a malcontent. His relationship to the “digital generation” that WIRED typically elevated to hero-status was slim at best. But he had chosen the right enemies. Julian Simon’s bet was a useful shorthand for “see, things are getting better. Government regulations never solve anything. A new era of abundance is arriving now, and anyone who disagrees is a fool or a liar.”

And that, more than advances in interconnected computing devices, was the story that WIRED wanted to tell.

The second bet occurred in 1995. Kevin Kelly, WIRED's Executive Editor, had long been enamored of the Simon-Ehrlich wager. And he had a target in mind: Kirkpatrick Sale, the author of an anti-tech diatribe titled "Rebels against the Future: The Luddites and their War against the Industrial Revolution.”

Kelly was deeply offended by the message of Sale’s book. So he planned an ambush of sorts. As Steven Levy explains in his writeup of the ultimate resolution of the bet (“A 25-year bet comes due: Has technology destroyed society?”)

Kelly hated Sale’s book. His reaction went beyond mere disagreement; Sale’s thesis insulted his sense of the world. So he showed up at Sale’s door not just in search of a verbal brawl but with a plan to expose what he saw as the wrongheadedness of Sale’s ideas. (…)

The visit was all business, Sale recalls. “No eats, no coffee, no particular camaraderie,” he says. Sale had prepped for the interview by reading a few issues of WIRED—he’d never heard of it before Kelly contacted him—and he expected a tough interview. He later described it as downright “hostile, no pretense of objective journalism.” (Kelly later called it adversarial, “because he was an adversary, and he probably viewed me the same way.”)

Sale warned in the book that we were on the verge of imminent societal collapse. Toward the end of the long, testy interview, Kelly tries to pin Sale down on when, exactly, he expected this collapse to occur. Again, quoting Levy:

Sale was a bit taken aback—he’d never put a date on it. Finally, he blurted out 2020. It seemed like a good round number.

Kelly then asked how, in a quarter century, one might determine whether Sale was right.

Sale extemporaneously cited three factors: an economic disaster that would render the dollar worthless, causing a depression worse than the one in 1930; a rebellion of the poor against the monied; and a significant number of environmental catastrophes.

“Would you be willing to bet on your view?” Kelly asked.

“Sure,” Sale said.

Kirkpatrick Sale was no Paul Ehrlich. Their predictions of impending doom were similar, but he had neither Ehrlich’s platform nor stature nor success. Where Julian Simon was the small fry, picking a strategic fight against a more powerful rival, Kirkpatrick Sale was a less well-known figure than WIRED’s Kevin Kelly.

I don’t identify with the man, but I do feel like I know the type. I spent my teens and twenties in the environmental movement. You meet a lot of Kirkpatrick Sale-types in environmental activist circles. They’re well-meaning, but impossible to work with on anything pragmatic. They tend to stretch out the meetings, insisting on narrating their latest self-published book that will surely open people’s eyes once and for all. They aren’t much help, but they don’t mean any harm.

By happenstance, I actually read Sale’s book as an undergrad. It wasn’t on the syllabus, but I decided to write a seminar paper on anti-technology movement for a history class. It was one of the only books in the library on the topic. It didn’t leave much of an impression, even in my impressionable youth. (Sale’s editor would later describe the book as “not a bestseller.”)

So I find the force with which WIRED attacked Sale’s book a little jarring. The June 1995 issue featured both culture critic Jon Katz writing a 3,500-word book review of all the reasons why Sale was a “Luddite wannabe,” destined to suffer a fate of “utter defeat, accomplishing nothing,” and Kevin Kelly’s 5,500-word “interview with the Luddite.” No other book received such a volume of critical coverage in the 30-year history of the magazine. It was like moving to Defcon 1 over a flock of seagulls.

I have read every interview and column and prediction that Kevin Kelly has written for WIRED magazine. I have read most of them twice, in fact. And this interview is, as far as I can identify, the ONLY one where Kelly asks a single combative or cutting question. It clearly struck a nerve.

When I noticed this interview during the initial 2018 readthrough, I took copious notes. I referenced it in my article for the magazine’s 25th anniversary:

Back in 1995, when Kevin Kelly made his $1,000 bet with Kirkpatrick Sale that in 2020 we wouldn’t even be close to economic collapse, class warfare, or widespread environmental disaster, the pages of WIRED told a story that supported his confidence. Judging from WIRED’s recent reporting—about the climate, discourse on social media, and international relations—the bet has, at the very least, gotten a lot more interesting. (“He is obviously losing,” Kelly says of Sale. “We should find him to make sure his check is still good.”)

Kelly’s confidence surprised me at the time. It hinges, I suppose, on how charitably we ought to read the terms of the bet. In the 1995 interview itself, Kelly declares:

I bet you US$1,000 that in the year 2020, we're not even close to the kind of disaster you [Sale] describe—a convergence of three disasters: global currency collapse, significant warfare between rich and poor, and environmental disasters of some significant size. We won't even be close. I'll bet on my optimism. [emphasis added]

This bet was much more haphazard than the Ehrlich-Simon wager. It has the texture of a dare. And I think there are two ways to read the wager:

(1 - uncharitable) Kirkpatrick Sale says that global currencies will have collapsed, the rich and poor will be engaged in warfare, and the we will have complete environmental devastation by 2020. Have these three disasters occurred, yes/no?

(2 - charitable) Kirkpatrick Sale is a pessimist, and believes the world will be worse off in 2020 than it is in 1995 in terms of currency stability, economic inequality, and environmental disasters. Kevin Kelly is an optimist, and believes the world will be better off in 2020 than in 1995 in all three of these categories. In which direction has the world moved in the intervening quarter century? Toward Sale’s pessimism or Kelly’s optimism?

As Steven Levy reveals in his article, the two men agreed on Bill Patrick, who had once edited each of their books, as the judge of the outcome. And Patrick selected the first, uncharitable reading of the wager. Kevin Kelly had successfully pinned Kirkpatrick Sale down. Sale agreed to the bet. The question at head was whether Sale’s three-headed apocalypse had, in fact, arrived. And, by that measure, Bill Patrick decided in Kelly’s favor. Even at the end of 2020, at the height of the pandemic, global currencies had not collapsed, the rich and poor weren’t at war, and the environment… well, Patrick tallied that point in Sale’s favor.

I have always leaned toward the second, more charitable interpretation. Kelly instigated this bet, and badgered Sale into accepting it. Kelly insisted that “we [wouldn’t] be even close. I’ll bet on my optimism.” If we are going to judge the doomsayers harshly for their misplaced (or at least mistimed) pessimism, shouldn’t we do the same for the prophets of boom?

I wrote about this bet another time, in January 2020, also for WIRED, in an essay about the Long Now Foundation’s 10,000-Year Clock:

Even back in 1995, this was a bet Kirkpatrick Sale never wanted to win. The original interview concludes with Kelly boasting, “Oh, boy, this is easy money! But you know, besides the money, I really hope I am right.” Sale ruefully replied, “I hope you are right, too.”

In recent years, WIRED has covered the environmental devastation of Puerto Rico and vanishing Antarctic glaciers. The magazine has covered the rise and fall of cryptocurrency. The magazine has covered the Occupy movement. And WIRED’s 2020 coverage has already included an article on the Australian wildfires that included the subheading “Welcome to the hellish future of life on earth.” Just reading the coverage in this magazine, the trendlines don’t appear good for Kelly’s optimism. We face greater economic inequality, greater social instability, and worse environmental disasters than in 1995.

It took a year for Kirkpatrick Sale to admit his defeat. He eventually agreed to send a check to Kelly’s Long Now Foundation. Kelly, in the aftermath of his victory, doubled down on his optimism, insisting that technological advances would soon solve all the world’s woes. He remains, as ever, confident in his optimism.

That optimism mystifies me. I cannot imagine we are inhabiting the future that Kelly and his peers envisioned back then.

I’m still haunted by that final line from Kirkpatrick Sale. “I hope you are right, too.”

There’s an old saying from my activist days: “environmentalists are the only people predicting the future who want to be wrong.”

It would be so nice if the libertarian techno-optimism of the 90s been actually been right. What a wonderful world that would be. I would love for my kids to be growing up in the world they imagined we were building. But does anyone honestly believe that?

Environmentalists are not inherently opponents of technological advances. When I was coming up through the movement in the 1990s, we were excited about windmills and solar panels and hybrid cars. We ran big campaigns to support mass transit and mixed-use development. And certainly, today, the movement’s biggest domestic victory is a massive spending bill designed to jumpstart industrial policy in the clean energy sector.

But environmentalists, historically, have pursued our ideological goals in the arena of government policy. And we are worriers — we believe in the precautionary principle, and take seriously Aldo Leopold’s missive that “the first rule of intelligent tinkering is to save all the parts.”

I think that’s why old-WIRED had such vitriol towards environmentalism. You can see it in the coverage of these two bets, but I could also show you plenty of other examples later in the magazine’s run.

WIRED wanted us to all be optimists, to cheer on the scrappy technologists who were building a better tomorrow, and to keep the government out of their way.

Environmentalists focused on the negative externalities of all this economic growth. They questioned whether new technologies were inherently positive. And they launched citizens’ movements that pressured government to play an active role.

The Paul Ehrlich-style of apocalyptic predictions certainly has not aged well. It deserves plenty of critique. (And it has gotten plenty. Check out Michael Hobbes and Peter Shamshiri ripping The Population Bomb apart on their “If Books Could Kill” podcast.)

And Kirkpatrick Sale, god bless him, has faded into deserved obscurity. We should leave the poor fellow there.

But I think we ought to notice the level of vitriol that 90s WIRED directed at environmental advocates. The old WIRED ideology is still very much alive — not so much in the pages of the magazine anymore, but among the tech elites who are now some of the wealthiest and most powerful people in the world.

Elon Musk and Sam Altman and Peter Thiel don’t just expect us to applaud their every new invention and keep government out of their way. Their worldview doesn’t just anoint heroes; it also includes villains.

And those villains? Those critics of technology? Those pragmatists insisting that governments will have to play a central role in combating catastrophic climate change and maybe a few unregulated corporations building blockchains and scanning eyeballs aren’t setting us on the path to shared prosperity?

I think it’s plain as day, here in 2023, that we critics are not the problem.

In the Simon-Ehrlich thing, as I think you acknowledge, no matter who won, we all lose, because they're both terrible futurists--there are a zillion ways you can falsify cornucopianism (or point out that it always depends on the idea that somehow we will invent a magical just-in-time solution to a catastrophe right at the moment of its occurrence; when you observe that this wasn't so in many past catastrophes, the cornucopian moves the goalposts and goes for a variation of Keynes' in-the-long-run by saying that eventually everybody got better and humanity still survives so hakuna matata baby. Only, you know, that's not because somebody came up with a brilliant solution eventually; it's mostly dumb luck or because almost all of the somebodies in one place died and eventually somebody else moved in, or all the somebodies in the catastrophe place took off and went to a new place where nobody was that wasn't so catastrophic. We're fresh out of places to move to now (and fuck off, Elon, Mars is not an option).

But Ehrlich, man, not only was he wrong, he and his bunch were pushing a bunch of policy ideas that thankfully were not as widely adopted as they might have been, like mandatory sterilization; there was a powerful stench of eugenics floating around his discourse. And his ideas have remained in the cultural air in some really gross ways--you absolutely cannot convince a major fraction of educated people of my age that global population growth turned out not to be that big of a problem and that for the most part, population growth fell off without strong government interventions, that the real issue was and remains the distribution of resources, food, etc.

Kelly and Sale is a more complicated thing as you say because the bet was more complicated and because Kelly and Sale are both slightly more complicated thinkers and prognosticators than Simon or Ehrlich.

About Ehrlich, I suppose the problem is not in being apocalyptic to get people's attention, but what do you do with that attention once you have it? Choosing to be more apocalyptic since that worked before is not the best decision. Tech optimism is much the same thing. Look at all the magical tools we have! Surely all we need is more magical tools to fix any problems caused by our magical tools. What could possibly go wrong?