OpenAI has an unsubtle communications strategy.

The load-bearing relationships between futurity-vibes and finance

I was reading Casey Newton’s latest newsletter last night and got the feeling he had almost landed on a very big point.

Casey writes:

“Every time I feel like progress in artificial intelligence is beginning to slow, a week like this one hits — and suddenly, it's all I can do to keep up.”

He goes on to discuss OpenAI’s announcement this week that the company is acquiring Jony Ive’s one-year-old startup, IO, for $6.5 billion in stock. Ive is Steve Jobs’s former right-hand-man, and the designer of the iPhone and Apple Watch. He is effectively Silicon Valley royalty. OpenAI has just signaled that it is going to start making hardware, and has recruited the world’s most famous hardware designer to lead the effort. Quite a week for the AI news beat.

But there’s another way to interpret that opening line. OpenAI runs an incredibly effective comms operation. They are engaged in a communications campaign. And the purpose of the campaign is that whenever it starts to feel like progress in AI is slowing down, there needs to be another announcement or product demo that makes it feel like the future is fast-arriving.

Or, put another way, the reason OpenAI just spent $6.5 billion in stock to bring Jony Ive on board was that it was beginning to feel like progress in AI was slowing down, and they had to keep priming the pump.

(It’s actually way less than $6.5 billion. OpenAI already owned 23% of IO. And another chunk of IO is owned by Open AI’s Start-Up Fund, which is controlled by Sam Altman himself. So this is much more like the news last month that Elon Musk’s X.AI was purchasing Elon Musk’s X.com for $33 billion in stock. It’s mostly just a small number of players shifting stock and ownership structures around.)

I mean, take a look at this introductory video they released. It is almost 10 minutes long. It is filled with positive vibes from two major figures in the tech world. And it only has the barest concept-of-a-plan for the actual product they hope to someday design.

They intend to sell 100 million devices someday. It won’t replace your phone or your laptop. It’ll be a third essential thing. Details TBD.

Viewed on the merits, outside of the strategic need to keep the vibes from getting stale, how does this merit a major news cycle? Altman and Ive have been working on a hardware device together for TWO YEARS. OpenAI already had a major stake in the company. They do not have a prototype. When they have a prototype, it will be substantively newsworthy. But that won’t happen for quite awhile.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this type of strategic communication campaign. It can be used for good or for evil or for a secret, third thing.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say the strategic communication campaign is a necessary condition for a company like OpenAI to succeed and eventually become profitable.

OpenAI is a cash furnace. That’s by design. Focusing on growth over profitability is kind of the informal motto of Silicon Valley’s VC class (cf: “blitzscaling”).

For OpenAI to stay in operation and keep building the next generation of its product line, it needs constant infusions of investor cash. It needs the big money. Sovereign wealth fund money. Softbank money.

And that means it has to feel like the future. (As I’ve written previously, Silicon Valley runs on futurity.)

In order for the engineering team to build the thing that lives up to your ambitions for the future, they need (a) money and (b) time.

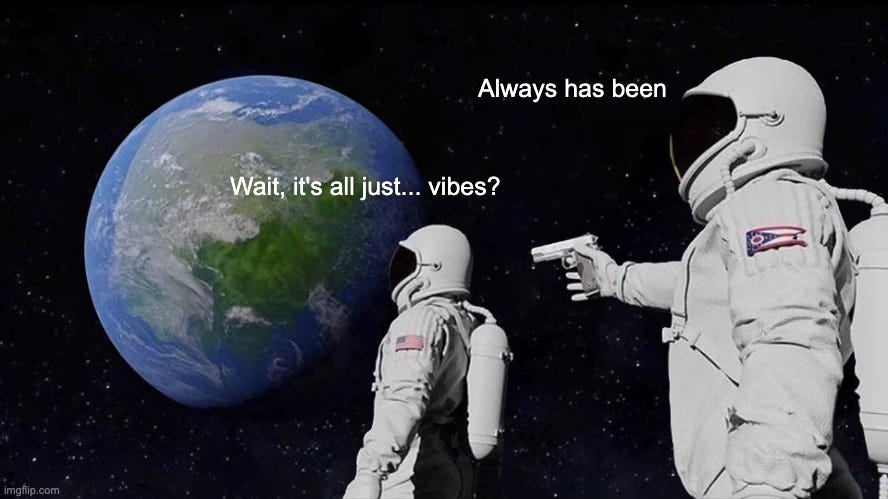

In order to keep the money spigot flowing at full force across time, you’re going to need to maintain that halo of futurity. Investor cash isn’t premised on deep technical knowledge. It’s premised on hopes and hunches about future returns. They are participating in a Keynesian Beauty Contest. It’s vibes all the way down.

And the way you hold on to futurity is by executing a strategic comms plan that maintains a steady drumbeat of exciting/promising stories. The substance of the stories is less important than the cadence. The cadence is the point.

Analytically, that means we ought to take the cadence as a given when interpreting these news events. It is no surprise that OpenAI had a big announcement this week. It is a surprise (and a very bad one for OpenAI) that the only announcement they could muster right now was “uh hey we acquired the rest of Jony Ive’s and Sam Altman’s startup. They aim to have a killer product sometime down the road.”

If OpenAI were living up to its technical ambitions, it wouldn’t need to dip into these vague-intentions-of-a-plan to keep the drumbeat going.

Taking a step back from this particular headline, there is a broader theme I want to mention: there is, today, a profound connection between futurity and finance. That connection is relatively new. And it is substantively awful.

Earlier this year, I finally got around to reading Future Shock, by Alvin and Heidi Toffler. It is a delightfully bizarre book, a runaway 1970 bestseller, so successful that it ended up establishing the contours of professional futurism for decades to come.

(As is my habit, I livetweeted my reactions in a bluesky thread. If you want a few laughs, the thread is here.)

The thing that I enjoy about retrofuturism is that, when revisiting futures’ past, it becomes so remarkably clear that futurism is always really a statement about the present. Alvin Toffler’s method, to the extent he had one at all, was to check out the fringe subcultures and then assume they would eventually get huge and spread everywhere. So in 1970, people were trying communes. That’s the future. They’re renting homes instead of buying. That’s also the future. A few scientists have ambitions to build underwater cities. Great, sounds wild. The future! He never considers the possibility of non-adoption of technology, or technical failure, or social rejection, or intentional counteraction. He’s just trendspotting and declaring “alright now imagine a scenario where everyone does this someday in the future, and it works really well.”

The incredible thing about Toffler-style futurism is that you can use it to say anything. “People will live in temporary underwater cities.” “Society will value psychic fulfillment over material goods.” …It’s like a future-tense version of the “Charlie Brown Had Hoes” tweet. No we won’t. That’s not ever gonna be true.

This is deeply unserious stuff. It’s comforting in its simplicity. The futurist can use Toffler’s technique to say anything, so long as it is vaguely plausible and, more importantly, entertaining to the audience.

And that’s… fine, so long as we don’t take it seriously. There’s nothing particularly offensive about pundit-futurism as a low-stakes hobby. Old futurity - future shock era - was a different beast than what we have today. And that’s because of how everything has become financial speculation.

I mean, really, what was at stake when the Tofflers wrote Future Shock? It’s ridiculous, but it’s also mostly just light entertainment. We should worry about this stuff in direct proportion to its proximity to power. (The Toffler’s eventually did gain proximity to serious power, via Newt Gingrich. And that was, y’know, BAD.)

The successful futurist of the 1970s-1990s, following in Toffler’s footsteps, would write a speculative book, then get PAID on the lecture circuit. In the very-best-case scenario, maybe Orson Welles adopts your work into a documentary of the same name. (Watch it, linked below. It is WILD.) Then you set up a consulting businesses, designing scenarios for corporate clients. (*ahem* Global Business Network)

There was money in futurity back then. But it was, like, fly-first-class money. Not buy-your-own-private-island money.

Things changed around the late 1990s. That’s when the phase transition happened. And it would be oversimplifying things to say “it was all George Gilder’s fault.” But, ell oh ell, it wasn’t exactly NOT George Gilder’s fault either.

In the late 1990s, Gilder-the-futurist became Gilder-the-stock-picker-with-a-newsletter. Gilder’s stock picks moved markets (until they didn’t). Which meant there was real money to be made in telling the type of story that Gilder wanted to hear.

And that’s just a precursor to finance-eating-the-whole-economy. Inside every Silicon Valley company are two businesses. One is a business that attempts to sell products for more than it costs to make them. The other is a speculative stock, trafficking in vibes. So long as the latter doesn’t overshadow the former, that can be just fine. But (again ell oh ell), selling actual products in a competitive marketplace is for suckers and tourists. The real money, for the past couple decades, has been in vibes. If you want to get private-island rich, futurity is the name of the game.

Which brings us back to OpenAI and Jony Ive’s latest non-announcement.

There is a hidden curriculum that OpenAI and the rest of the Silicon Valley ecosystem operates under. Altman, in his past role as President of YCombinator, was one of its coproducers.

Focus solely on growth over profitability.

Tell a story that attracts initial investors, and then remain laser-focused on telling stories that attract the next round of investors.

You will be judged based on your globe-spanning ambitions, not on your actually-existing product quality.

The storytelling that drives futurity is orthogonal to the actual building and deployment of new products or technologies.

So invest heavily in comms. Tell the story that keeps the money flowing.

Then, hopefully, you can use that money and the time it buys you to deliver on your grand ambitions. (And if not… eh, better luck next time. The early investors still made out fine.)

The result is that everything becomes speculative finance. Sam Altman HAS to keep stoking the futurity vibes. That’s a material necessity, whether you’re an OpenAI critic or a booster. He needs the money spigot to keep flowing, which means maintaining investor confidence, which means keeping up the cadence of exciting-sounding news.

Maybe with enough money, time, and talent, OpenAI manages to build the next generation of computing. Or maybe OpenAI is a hype-bubble that eventually collapses like a dying star. Either way, the necessary precondition is that the company maintains the aura of futurity until it either gets there or runs out of public confidence — Fake it till ya make it, but as a trillion-dollar business plan.

It’s a rotten game. We have been playing it for far too long. The stakes have gotten way out of hand.

The least we can do is name it for what it is.

Casey Newton - "Every time I think I see a man behind the curtain a bright flash goes off and makes it really hard to see for a minute."

IOW, where vapourware was once just a method to stifle competitors and maintain the stock price, now it is a key part of the financial Ponzi scheme. When conglomerates were used to buy low PE stock earnings to create the illusion of growth to maintain a high PE, analysts eventually understood that game and acted accordingly. Now, large dollops of vaporware are used to create that exciting future, skip making any real business, and maintain the financial illusion. It is all smoke and mirrors. Do I detect a new version of the "South Sea" bubble?