What Should We Have Learned from the Collapse of the New Economy (1998-2000)?

History doesn’t repeat itself, but oh boy does this one rhyme.

[NOTE: this one is long enough that you’ll have to read it in a browser to see the whole thing. For readers who are curious about the book project, it should be worthwhile. This is a big chunk of an early draft of what will be chapter 3.]

Here’s how the future looked to WIRED’s Kevin Kelly, circa September 1999. I’m sharing this up front to get your blood boiling:

“Fast-forward to 2020. After two decades of ultraprosperity, the average American household's income is $150,000, but milk still costs only about $2.50 a gallon. (…) Hard-hat workers are paid as much as Web designers, and plumbers charge more for house calls than doctors. (…) Indeed, labor is in such short supply that corporations "hire" high school grads, and then pay for their four-year college educations before they begin work.

What the rich have in the year 2000, the rest have in 2020: personal chefs, stay-at-home moms, six-month sabbaticals. (…) Although tax rates have lowered, the amount of money flowing into state and federal budgets is awesome. Social Security has ample funds, and hundreds of thousands of schools, hospitals, and libraries have newly opened. Ambitious, large-scale public works are all the rage; there's a scandal over whose corporate logos appear on the space suits of the first manned mission to Mars.”

(Ah, well, nevertheless.)

This was from an article called “The Roaring Zeros.” The article was another of WIRED’s trademark optimistic scenarios. Much like 1997’s “The Long Boom,” this scenario was presented as a prediction-with-built-in-plausible-deniability. (It’s a prediction clad in fake mustache and jaunty hat.) Kelly wasn’t saying that we definitely would all have personal chefs and six-month sabbaticals in 2020. He was saying this would happen if the current conditions of “ultraprosperity” continued for decades. …And also that this was a realistic possibility. Downright likely, in fact. Particularly if we all focused our attention on optimistic possibilities instead of getting mired in worrywart concerns like “what if the whole dotcom bubble pops and people lose their life savings gambling on worthless tech stocks?”

Kelly was in good company with his optimism. By mid-1999, tech journalism had merged with business journalism. The umbrella term for this era of financial swagger was the “New Economy.” WIRED magazine touted the “WIRED Index” (WIRX), a list of 40 companies that embodied the New Economy. Every month, the magazine featured a column bragging about how much better the WIRX was doing than the Dow or the NASDAQ. The digital future was a future of economic abundance. Everyone was going to be rich. And the future was arriving now.

The closer you looked at the Roaring Zeros, or the WIRX, or WIRED’s three-part series, “The Encyclopedia of the New Economy” (sponsored by Anderson Consulting, archived link here), the less sense any of it made. The New Economy was about “decentralization” and “adhocracy.” Some of the biggest companies in the WIRX were Disney, Marriott, and Monsanto. (Ah yes, that famously decentralized and adhocratically-run Walt Disney corporation…) But you weren’t meant to look closely. The whole point of New Economy-style futurism was to keep people excited and engaged, united in the belief that this time is different, and we will all be rich.

There is a striking parallel between reading WIRED during the late boom years (1998-2000) and reading tech publications during the last crypto hype cycle (2020-2022). It seems this is a pattern we are doomed to repeat, until and unless we actually learn from it.

So I think it’s worth spending some time looking back at the New Economy-tinged futurism of the late dotcom boom years. The excessive spending, overheated rhetoric, and bad financial advice of that year had consequences that still reverberate today. The people who got rich off the dotcom crash would go on to become the financial titans of Silicon Valley — a new Venture Capital elite, convinced of their own self-righteousness. We keep reliving the mistakes of the past because we keep rewarding the people who profited from them.

The dotcom boom spanned five years, beginning in 1995 with the Netscape IPO and unraveling in March 2000. (Six months after Kelly asked his readers to believe in a future of ultraprosperity.) But the late boom years had a distinct texture that separated them from the early boom years. The early boom was full of revolutionary fervor — hailing the World Wide Web as the most transformative invention since the printing press. The call-and-response of the late boom was more coarse: its adherents insisted that We Are All Going to Be Rich! Tech stocks were soaring in value, and retail investors were (supposedly) reaping the rewards. The business cycle had been vanquished. The good times would never end. It was the dawn of the “New Economy.”

This change in tone was primarily attributable to the mere passage of time. When you have been rich-on-paper for three weeks, it’s easy to believe it’ll all vanish in a heartbeat. When you have been rich-on-paper for three years, people tend to acclimate, to accept it as the new status quo and to develop elaborate explanations for why this all, in fact, makes sense.

John Cassidy captured it well in his 2002 book, Dot.con: The Greatest Story Ever Sold

“Journalists weren’t immune to the logic of the bubble. In the early stages of a speculative boom it is easy for a financial columnist to be a skeptic, but after a year or two of rising prices most readers get tired of pieces predicting a crash. The news is that investors are getting rich. Other people want to know how to mimic them; editors want to satisfy this demand.”

The salient facts of the late boom were (1) people kept getting online and (2) stock prices kept going up. The former meant that Internet businesses conceivably didn’t need to be profitable today — they could tell a story to investors that they would be profitable later, once they dominated this new, emerging industry. The latter leant credence to the possibility that this time would be different. After all, people were calling it a bubble for years, and it kept not-deflating.

[NOTE: I wrote about this phenomenon way back in August 2022, in an article titled “The Money Has to Come from Somewhere.” I promise all of this pieces will fit together smoothly in the book manuscript.]

Again, if this all sounds reminiscent of the 2020-22 crypto boom… well, yes, it is. History doesn’t repeat itself, but oh boy does this one rhyme.

The best I can describe it is that WIRED during the early boom has the feel of the Washington Wizards with an early lead at home against an actually-competent basketball team. The scoreboard may reflect that things are going great, but no one in the arena expects it to last. The score is tangible, but transitory. Real fans know better than to get caught up in it.

The late boom years feel more like a Celtics game. The whole arena is brimming with confidence. The team is going to win. The team is destined to win. Any call from a referee that doesn’t go their way is an offense against God, man, and nature. There is a general sense that we are winning because we deserve this. And yet, also, they somehow manage to see themselves as underdogs.

(The late boom years, in other words, are so much more obnoxious than the early boom years.)

WIRED during the late boom had the feel and the (literal) heft of a business magazine. The magazine physically swelled in those years. It was cluttered with advertisements, laden with profiles of all the good and great corporations that were ushering in the digital revolution by setting up websites or fixing their internal logistics.

This was all part of the New Economy, the reader was confidently assured. The New Economy was going to make everyone rich.

And WIRED’s readers would be first in line.

The WIRED Index

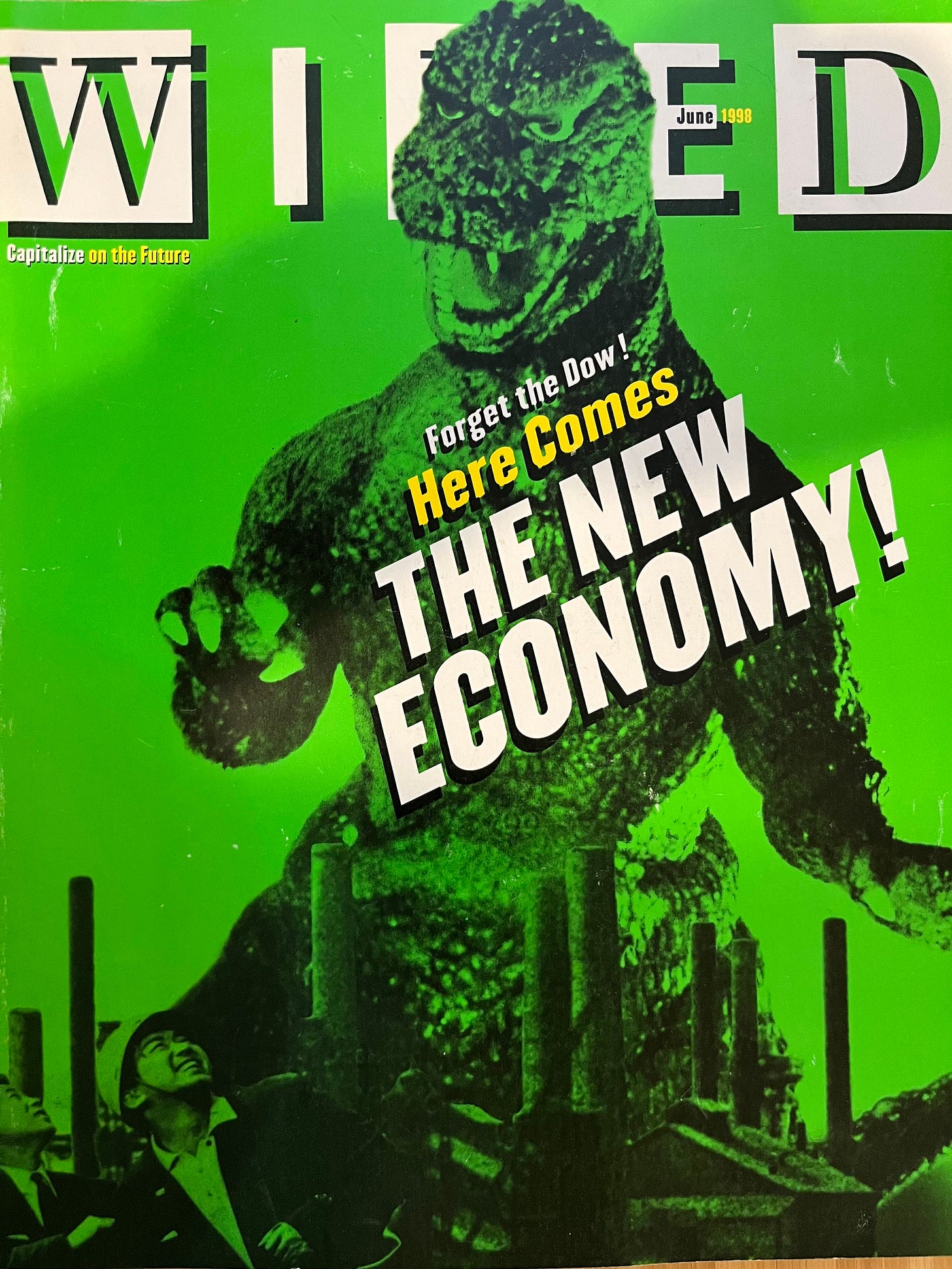

The WIRED index premiered in June 1998 in a cover story declaring “Forget the Dow! Here Comes the New Economy!” From 1998 through mid-2000, the Index was a constant feature in the magazine, trumpeting how much better of an investment vehicle WIRX was versus the Dow Jones or the NASDAQ.

The Index was an clunky melange of old and new. It included the Big Tech firms of the day (Dell, Nokia, Intel, Microsoft) and financial service companies (Charles Schwab, State Street Corporation), but it also included the likes of Daimler-Benz, Marriott International, Monsanto, Wal-Mart, and Walt Disney. It doesn’t appear to me as though there was much rigor behind the investment thesis. (But, to be fair, I’m not sure there ever really is.)

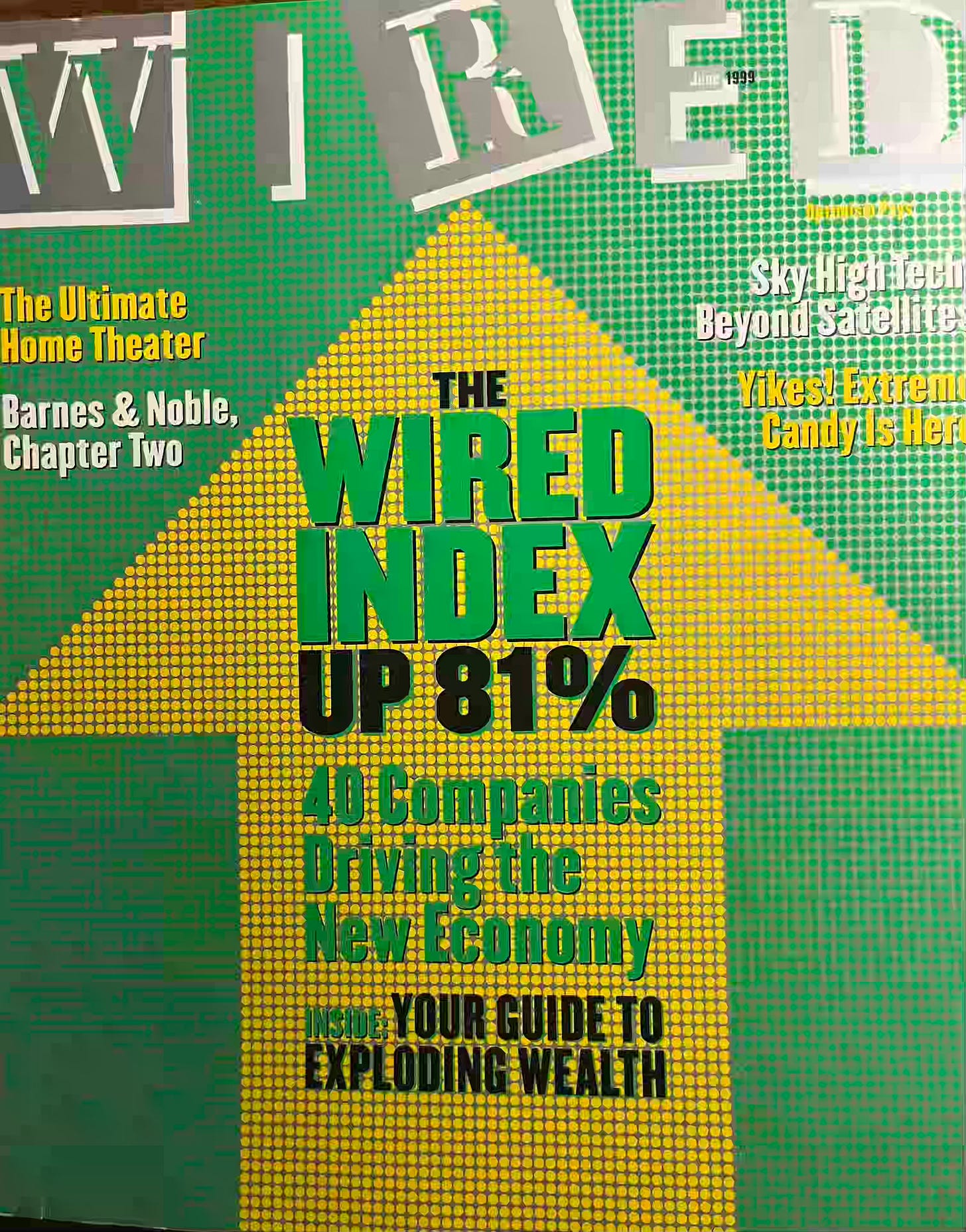

A year later, the cover story boasted “The WIRED Index Up 81%.” The lead story declared “The future is undervalued” and bragged “In the 12 months since [launch], the WIRX has rocketed 81 percent, far outperforming every other broad-based index. Like us, Wall Street seems to smell the future in the Index companies. And they like it.”

The June 2000 issue went to press in April, just a month into the dotcom crash. The magazine adopted a keep calm and carry on posture, trumpeting “Keep Cool, the new economy is hotter than ever.” This was the start of what I would call the magazine’s phantom limb period, when the dotcom bubble had burst and tech enthusiasts were acting as though it was just a minor scratch.

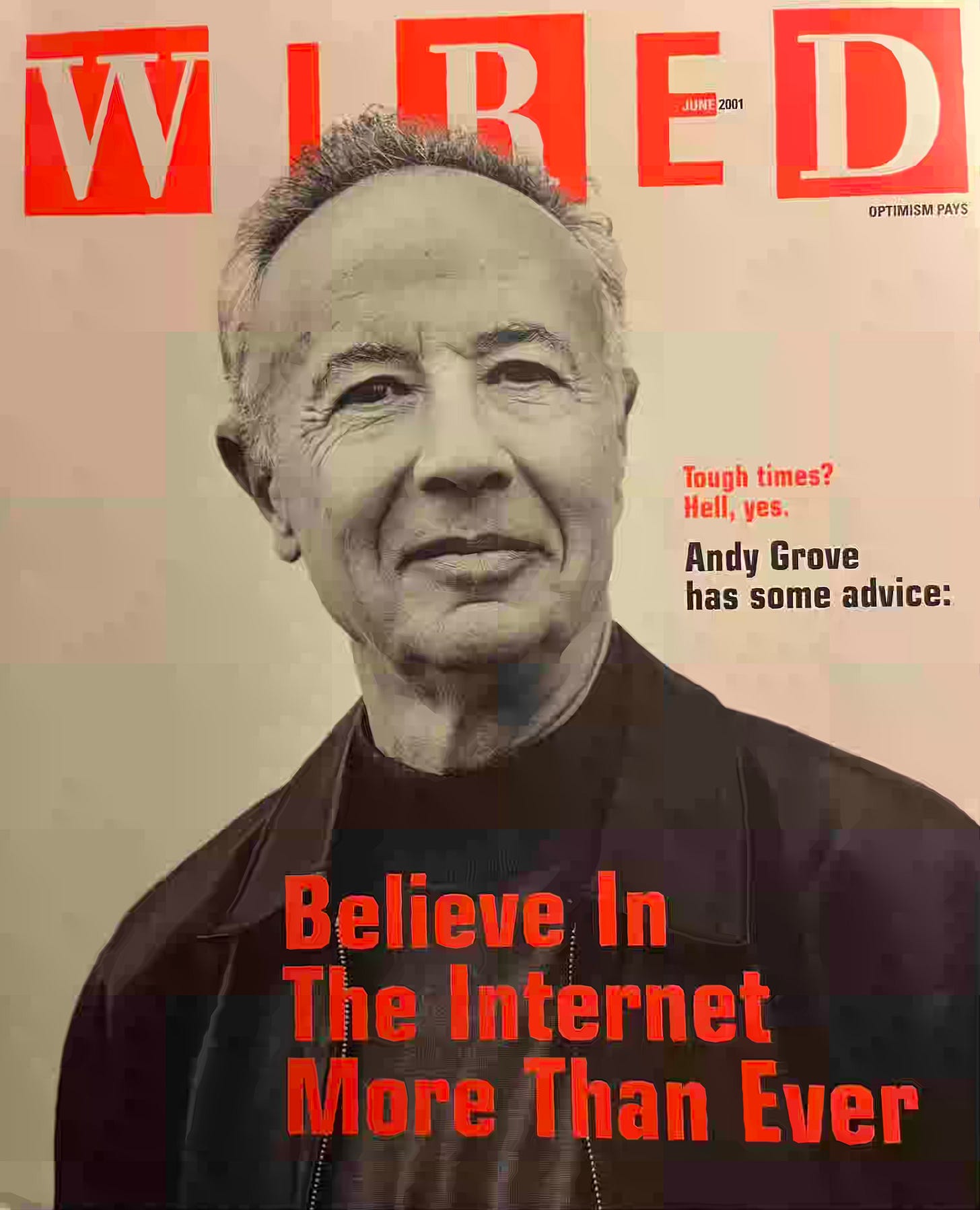

By June 2001, reality had set in. The WIRED index was replaced as the cover story by a(n admittedly fantastic) interview with Intel’s Andy Grove. The message on the cover: “Tough times? Hell yes. Andy Grove has some advice: Believe in the Internet More Than Ever.”

The following year, in July 2002, the magazine revisited the index. James Surowiecki wrote the lead article, titled “The New Economy Was a Myth, Right?” Surowiecki admitted that the rhetoric of New Economy boosters had gotten out of hand, but attempted to reframe recent history. According to Surowiecki, weren’t the boosters kinda-sorta correct?

“No doubt, some advocates of the new economy went overboard touting its revolutionary impact. The business cycle is still with us. (…)

The climate of exaggeration and hype made it easy for sober-minded observers to dismiss the new economy. Yet for all their excesses, the prophets of the new order understood what was happening better than the grumbling bears did. (…)

The stock market at the tail end of the 1990s was, of course, a bubble, based on unsustainable expectations and driven by the theory of the greater fool. (…)

In fact, the real winners were not greedy investors or Wall Street hucksters. The victors were consumers and workers, who reaped the benefits of inflation-free prices, low unemployment, rising wages, and a booming GDP.”

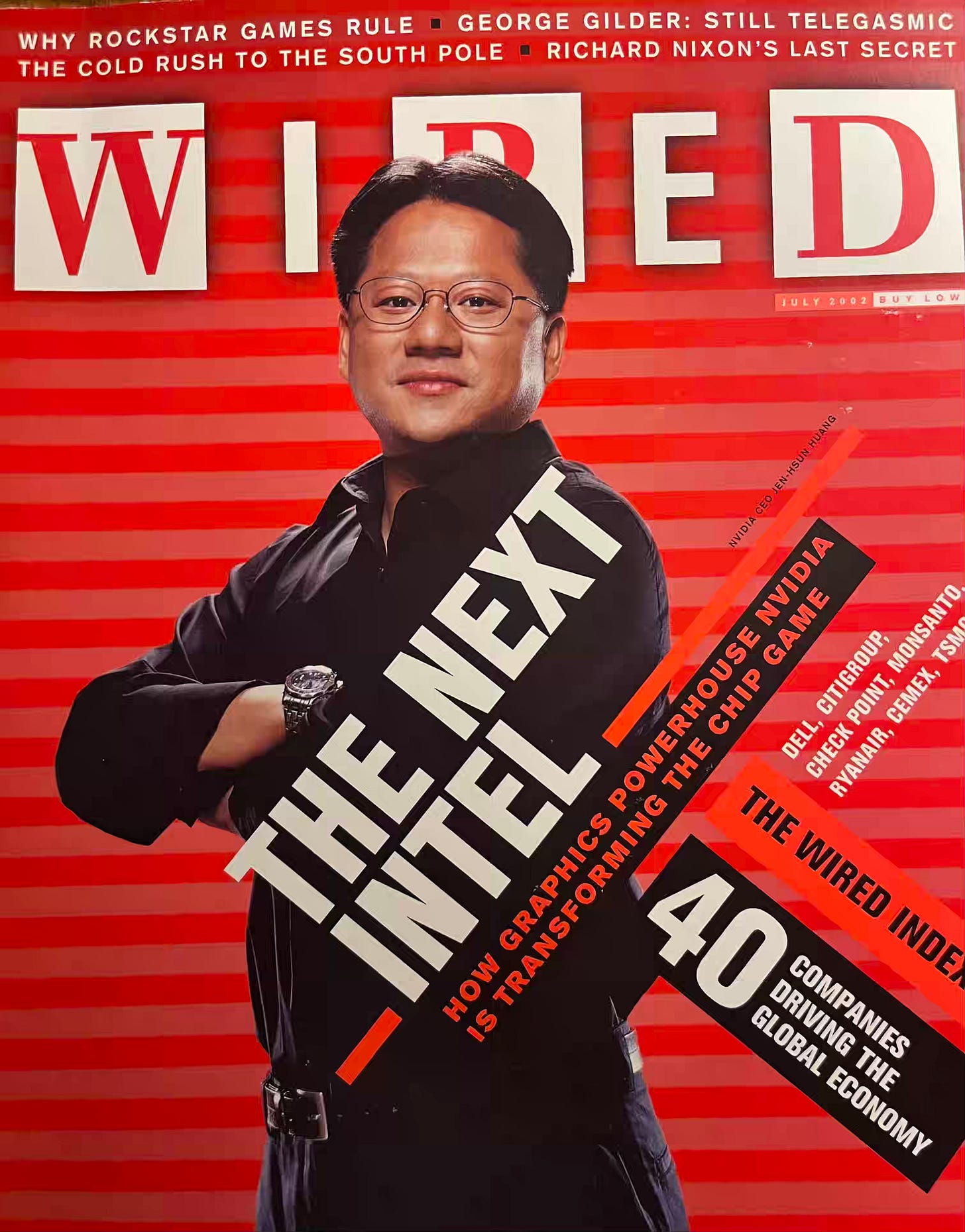

By 2003, the Wired Index had been renamed and downgraded to the “Wired 40.” The magazine was no longer trying to compete with the Dow or the NASDAQ. It was just profiling interesting companies like NVIDIA and Google. Only 10 of the original 40 WIRX companies were still included. Some had gone bankrupt. Some had turned out to be famous frauds (Enron, Worldcom). Others just hadn’t lived up to the magazine’s heady expectations.

The minimal explanation here is, as Surowiecki put it, “the business cycle [was] still with us.” The economy goes through booms and busts, and the rhetoric of the boom times always seems farcical with hindsight.

But I think there’s more to it here. Both the stakes and the aftershocks of the New Economy deserve closer attention.

The New Economy, Defined

There is an amorphous quality to the New Economy. It was never laid out as a set of predictions or claimed that could be tested or disproven. Economists like Paul Krugman though it was vapor. It had the consistency of a collective PowerPoint presentation, with broad generalizations that sound exciting and insightful, so long as no one dwells on them.

In 1998, WIRED published a three-article series called “Encyclopedia of the New Economy.” It was sponsored by Anderson Consulting. I can’t link to it, because it isn’t available online. (That’s okay. It’s nonsense.) [thanks to an eagle-eyed reader, I now have a link!]

Here’s how they defined the New Economy:

“When we talk about the new economy, we’re talking about a world in which people work with their brains instead of their hands. A world in which communications technology creates global competition — not just for running shoes and laptop computers, but also for bank loans and other services that can’t be packed into a crate and shipped. A world in which innovation is more important than mass production. A world in which investment buys new concepts or the means to create them, rather than new machines. A world in which rapid change is a constant. A world at least as different from what came before it as the industrial age was from its agricultural predecessor. A world so different its emergence can only be described as a revolution.” -John Browning and Spencer Reiss, “Encyclopedia of the New Economy, Part 1” [emphasis added]

I think it’s worth keeping that bolded passage in mind, because folks like Surowiecki will argue in 2003 that, even if it was a bubble, the promoters of the new economy were correct about the underlying phenomena.

The economy was changing in the late 1990s. But the economy is always changing. And, with hindsight, it seems as though the story of the 1990s was less about revolutionary technological abundance and more about union decay, an expanding service economy, and the financialization of everything. This was also a period of adding new “retail” daytrading investors (aka “Dumb Money”) into the financial sector, which was a direct contributor to the stock market frenzy which all the New Economy-talk was meant to justify.

The overheated rhetoric of the New Economy boosters had a load-bearing quality. It wasn’t just idle chatter that got out of hand. It shaped markets and investment strategies. It advanced some causes and concerns, while limiting others. It had winners and losers. And (contra-Surowiecki), the long-term winners were definitely not “consumers and workers.”

We do not, today, live in a world where innovation is more important than mass production. Apple and Amazon aren’t trillion dollar companies because of how innovative they are, or how good they are at creating “new concepts” (what the hell does that even mean?!?) They captured market share and gained control of multiple segments of their supply chains.

But the apostles of the New Economy appear, in retrospect, to have been engaged in a political project. They were defending the interests of a particular constellation of companies and economic interests, insisting both that this is good and this is inevitable. And this was a political project that undermined unions, deregulated the financial industry (and every other industry), and called for reducing tax burdens on investment vehicles. The bold idea was to free up the market to do exciting, innovative things that only markets could do. (Y’know, like the credit default swaps that will blow up the financial system eight years later.)

Looking back on these pronouncements today, what’s most striking is how many of them were not just wrong, but also incoherent. The closer you looked, the less sense any of it made.

The term “New Economy” is clearly tied to the dotcom boom. I searched the term using the Google Books Ngram Viewer, and it displays a steep increase in usage throughout the dotcom boom, followed by a 2003 peak and a gradual decline. Generally speaking, the New Economy was just a blanket explanation for “line goes up, and will keep going up forever.”

Kevin Kelly introduced the New Economy to WIRED’s readers with a September 1997 article, titled “New Rules for the New Economy.” In 1998, he turned the article into a book. The article introduces twelve “laws,” all of which purport to explain how the revolutionary New Economy differs from the old economy.

The laws are little more than food-for-thought. There’s the “Law of Connection” (Embrace Dumb Power), and the “Law of Exponential Value” (Success is nonlinear), the “Law of Inverse Pricing” (Anticipate the cheap), and the “Law of Devolution” (Let go at the top). Not all of these laws operate simultaneously, and a few seem to openly contradict one another. But the overarching point is that, thanks to the internet, business is different now, or at least it will be soon.

Fair enough, I suppose. But this ends up being indistinguishable from pundit-futurism. For instance, Kelly begins the article by proclaiming, “wealth in this new regime flows directly from innovation, not optimization; that is, wealth is not gained by perfecting the known, but by imperfectly seizing the unknown.” Tell that to Apple, Google, Facebook, and Amazon, all of which only became profit-generating behemoths by focusing on optimization, not innovation.

What Kelly is picking up on in 1997 is that the Internet is experiencing hockey-stick growth. People are getting online, sending emails, interacting, searching for information. Certainly that will amount to something! The revenue models are still nonexistent in 1997, and valuations are farcical. But it’s still so early. Eventually, there are sure to be significant business applications. And presumably whoever identifies those applications first will have an advantage over the competition. (Disrupt or be disrupted, right?)

Thus we got a demand for economic sense-making. And what the people with money and power most want to be told is that the good times will continue, so long as they keep doing what they already wanted to do. New Rules for a New Economy is the type of business book that gets you invited on the speakers circuit. And that’s where the real money in thought-leadership is.

New Economy-style futurism keeps growing in popularity so long as the stock market continues to reward anything that can pose as a tech company. It’s just a hype cycle. Tech is being judged based on its potential, not its results. A lot of paper wealth is being created. Every month, reasonable people who say “this makes no sense/it’s a bubble” are proven wrong by the wisdom of the market. New Economy futurism doesn’t have to do much heavy lifting. It just has to offer a comforting narrative for why this time is different. The stock market provides all the necessary supporting evidence. (WIRED must understand the late-90s economy better than Wall Street — just look at how well the WIRED Exchange is doing!)

Some New Economy thinkers focused on globalization instead of technology. Walter Wriston was fond of discussing how the “velocity of money” had increased. The end of the Cold War meant new markets were opening up, and countries were being pressured to sign treaties and enact policies that were advantageous to global corporations. Wriston, the former chair of Citibank, saw all of this as good for banking. He figured, by extension, that it would be good for the world.

Others were naive technological determinists. George Gilder insisted that Moore’s Law was extending beyond computer chips, and could be spread to virtually every sector [NOTE: I’ll be writing a separate piece on the rise and fall of Gildernomics]. He managed to lose basically everything in the dotcom crash, but still never figured out that Moore’s Law is just of an industrial target, not an inherent law of the universe.

And then, of course, there were the scammers.

The September 2000 issue of WIRED featured a story called “Money for Nothing,” by Dan Brekke. The article marked a turning point in the magazine’s coverage of the New Economy — the moment when it started to pay attention to the cons and the scams, instead of turning a blind eye to them while focusing on the positive.

It’s a fascinating, bizarre article, about a ponzi scheme called Stock Generation. As Brekke explains it, “StockGeneration sucked millions of dollars out of thousands of people at the speed of the Internet economy. Now the market's promoters have vanished, the Feds are sniffing, and the investors - they just want to keep playing the game.”

The scheme was embarrassing in its simplicity. StockGeneration created its own “virtual” stock market, and invited people to spend real money to buy shares in its pretend companies.

The game was touted as a combination virtual stock exchange and "Internet casino" that peddled shares in 11 nonexistent companies, with SG earning its keep by taking a 1.5 percent cut from each transaction. The site claimed that the shares had never declined in value, and that the return for one of the 11 stocks - a blue-chipper known as Company 9, or Golden Nuggets - would "always keep rising," netting investors a fat, locked-down profit.

"Having bought the shares today," SG's promoters wrote, "... you can firmly expect a 10 percent monthly profit ... without any worry whatsoever."

This is about as blatant of a ponzi scheme as you can imagine. Buy and sell stocks in pretend companies. We pinkie-swear that the prices will always go up. Everyone can get rich.

(I’m reminded of that passage from Anuff and Wolf’s Dumb Money, though: "Can everybody make money simultaneously?” "Yes. Every day there is a new IPO." Maybe the gap between StockGeneration and Day trading was a difference in degree, not a difference in kind.)

What makes this noteworthy is how the proprietors anchored it in the logic of the New Economy to make it seem more legitimate. Here’s Brekke again:

“The game might look like a scam to the untrained eye [its proprietors acknowledged] “but they explained that away by borrowing a catchphrase from the new economy: the Net changes everything. Because the world's online population - the source of SG's player base and revenues - was growing almost exponentially, there would always be plenty of new players and cash coming in to the game. (...)

See it for yourself: no ending in sight!" the SG site crowed. "We simply can't manage to keep up with the Internet." [emphasis added]

(10% returns on pretend stocks! Infinite wealth for everyone, because the potential player pool is expanding at the rate of the Internet and the whole economy is transforming from scarcity to abundance! Why, you’d be a fool not to play…)

StockGeneration was shut down by the SEC after a couple years of operation. Many desperate members of the player base complained, insisting that it was their money and they ought to have the freedom to lose it on a literally-pretend stock market if they wanted.

To me, the striking thing about this example is how thin the differences are between the language of this blindingly obvious ponzi in 2000 and the rhetoric of so many crypto startups in 2020. It was obvious that StockGeneration was a doomed ponzi scheme, because, again, these are pretend stocks in pretend companies. If you are buying stock in a pretend company, expecting it to sell it for a 10% monthly profit, where is that profit possibly going to come from other than a Greater Fool? And the explanation was that the new economy is just different. Growth would be endless. A new era of abundance was arriving, if only we could all see. You’ll get rich if you just stick around long enough.

We heard much the same thing from Alex Mashinsky and Celsius during the crypto boom. Mashinsky liked to insist that Celsius could guarantee 18% yields because the crypto economy was replacing the old economy, rendering the banks and all other middleman institutions obsolete. Growth would be endless, and a new era of abundance was arriving. “Either the banks are lying or Celsius is lying,” Mashinsky was fond of saying. (Spoiler: Mashinsky was lying.)

The crypto scams weren’t even original. They were like Bel Air or the Frasier Reboot, just rehashing an old, successful franchise.

I keep circling back to a line from WIRED’s 2001 Andy Grove interview. Grove, to his credit, never bought into the New Economy hype. He thought the Internet was overvalued in the late ‘90s, and thinks it is being undervalued in the aftermath of the dotcom crash. He talks an awful lot of sense in this interview:

“I have this vague feeling that, just as every generation thinks it invented sex, every generation thinks it created a new economy.”

Also (in a line echoed by this great, recent Cory Doctorow essay):

“What this incredible valuation craze did was draw untold sums of billions of dollars into building the Internet infrastructure. The hundreds of billions of dollars that got invested in telecommunications, for example. You know, when the information highway was the craze, the question I would ask [then-Bell Atlantic CEO] Ray Smith and [then-TCI chair] John Malone was, Who the hell is going to spend the billions of dollars it will take to build this thing out? You guys? The federal government? It’s not going to happen. And no one could give me an answer as to who was going to pay. Well, it turns out that the answer was the investing public, who rabidly ran and shoved the money into the hands of the infrastructure builders.”

But the line that really hits home is where he discusses how the excesses of the new economy affected venture capitalists:

“Previous booms didn’t make venture capitalists think they were God’s viceroys to the universe. (…) Where is Tom Wolfe when we need him? His Masters of the Universe were pathetic children compared with these people.”

Grove can’t see it in 2001, but it strikes me that this is the most important legacy of the New Economy. Because the people who escaped the crash with their millions intact — people like Marc Andreessen and Peter Thiel — would go on to became the next generation of venture capitalists. And, having been introduced to Silicon Valley during the excesses of the dotcom boom, these figures decided that the-way-things were-in-the-boom is just-the-way-the-world-is-supposed-to-works The people who made their fortune during the first boom-crash cycle became convinced of their own Darwinian superiority. The lesser figures had all been vanquished, and the new VC generation was sure that they had earned every penny and had earned their stature as Viceroys to the universe.

(This would’ve been less of a problem if we had taxed their extraordinary windfalls. But that was, uhhhh, really not the policy of the George W. Bush administration.)

We still amidst the the shadows of the spoiled New Economy today.

On the plus side, the irrational exuberance of those days was an unintentional public subsidy of internet infrastructure. Millions of people got connected to the Internet in those years, subsidized by companies with no business strategy beyond IPO pixie dust and faith that George Gilder knew what he was talking about. The Internet gets baked into our economy and our culture at a much faster rate than it would have otherwise.

But the New Economy was still primarily an exercise in separating Greater Fools from their money. And it advanced a political project of centering all of the power (and none of the responsibility) in the hands of a narrow class of investors and entrepreneurs. The people who got rich off the New Economy weren’t Machiavellian geniuses, manufacturing lies for the masses while keeping the gains for themselves. They were just the lucky few whose numbers hit in the roulette-wheel gambling economy, and they then comforted themselves by insisting that this was due to skill and foresight.

We keep reliving these mistakes, with bigger chunks of the global economy on the table, because we keep forgetting just how self-evidently silly the rhetoric was all along.

The New Economy was nonsense! It was an identical type of nonsense to the Number Go Up crypto nonsense! Instead of celebrating the new billionaires who emerged from the wreckage, and trusting them to do better next time, we should focus on the human tragedies, and develop safeguards so they can’t keep pulling the same ridiculous, profitable-only-for-them stunts!

That, ultimately, is what I think we should have learned from the collapse of the New Economy. Anytime the tech barons and financial analysts start insisting we’re entering a new economic age of limitless abundance, look very carefully at their slide decks and notice that its pure vapor. Stop treating billionaires like viceroys to the universe. Concentrating power in their hands and hoping they’ll do good with it never turns out well.

And stop letting them rewrite history to excuse the failures they profited from. That, too, is part of the political project they are enacting upon society.

Move fast! Break [other people's] things!

Holy false dichotomy. Optimization *is* innovation.