90's tech culture was a jumbled mess

A tour through WIRED's old "Fetish" product review section

I had writer’s block last week. So I decided to comb through the first five years of WIRED magazine’s product reviews. You know, like ya do.

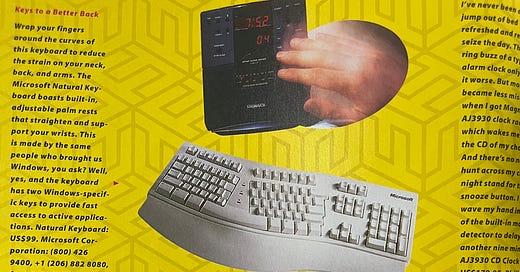

WIRED’s original product review section was titled “Fetish: technolust.” It’s a really interesting historical artifact, because the whole thing is just so… bonkers. I mean, take a look at this review page, from November 1994:

That’s four product reviews. Each gets a short paragraph. In the upper-left corner, they review an ergonomic keyboard. $99. Sure. In the upper-right corner, there’s a review of the latest clock radio. $179.95. Uh-huh. Lower-right, a high-end boombox. $999.95. Note from the future: That tapedeck is going to age poorly.

And then in the lower-left corner, they blurb the 43-foot Scarab Superboat, “the world’s fastest offshore V-hulled vessel.” $500,000.

Those first three products are going to be available at, like, Best Buy and Circuit City. The fourth is distinctly not available at any retail electronics outlet. What, um, what are we doing here, old-WIRED?

Reading through all the reviews, I made three notes.

(1) What early WIRED was engaged in here was aspirational marketing. The editorial team had an idea of the ideal “netizen,” an image they wanted to project. The product reviews were a winking attempt to will that consumer base into being.

Second, this is the result of the strange mashup of 70s counterculture and 80s yuppie culture that Fred Turner highlights in his classic book, From Counterculture to Cyberculture. These reviews have a lineage that dates back to the Whole Earth Catalog, but aimed at Gordon Gekko-types.

Third, many of the product reviews left me thinking about just how strongly people must have felt the effects of Moore’s Law at the mass consumer level, back then.

Let’s dig in.

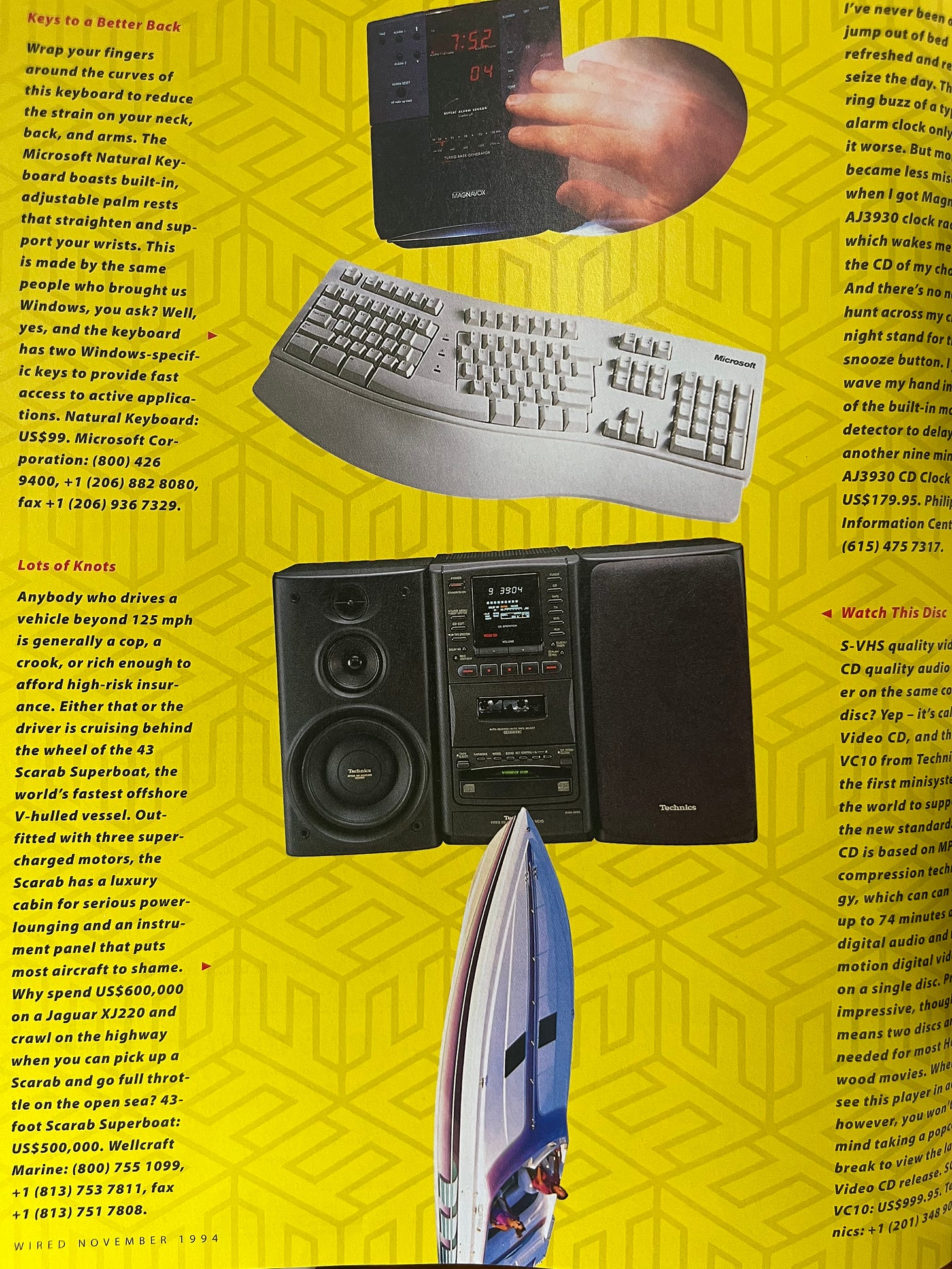

I made a little spreadsheet of all the product reviews from 1993-1997, along with their prices. You can see it below. I am terrible at data visualization. I’m so sorry.

I grouped the product reviews by year and by price cohort. ($1-9, $10-99, $100-999, $1K-5K, $5K-10K, $10K-50K, $50K-100K, $100K+). There were only 6 issues of the magazine in 1993, so it had half the product reviews of the later four years.

The first bit that stands out to me from this summary data is the story it tells about 1994. That was before the Netscape IPO and the dotcom boom. WIRED’s first feature story about the World Wide Web wasn’t even until October 1994. Tech culture that year was still mostly aspirational, still forecasting how usenet groups, interactive television, and CD-ROMs were about to change everything. And their product review section was filled with $3,500 chairs and $1,500 nightscopes. Later years retained the gaudy edge, but you can see a steady increase in the $10-99 price category and a slow decrease in the $5K-10K category.

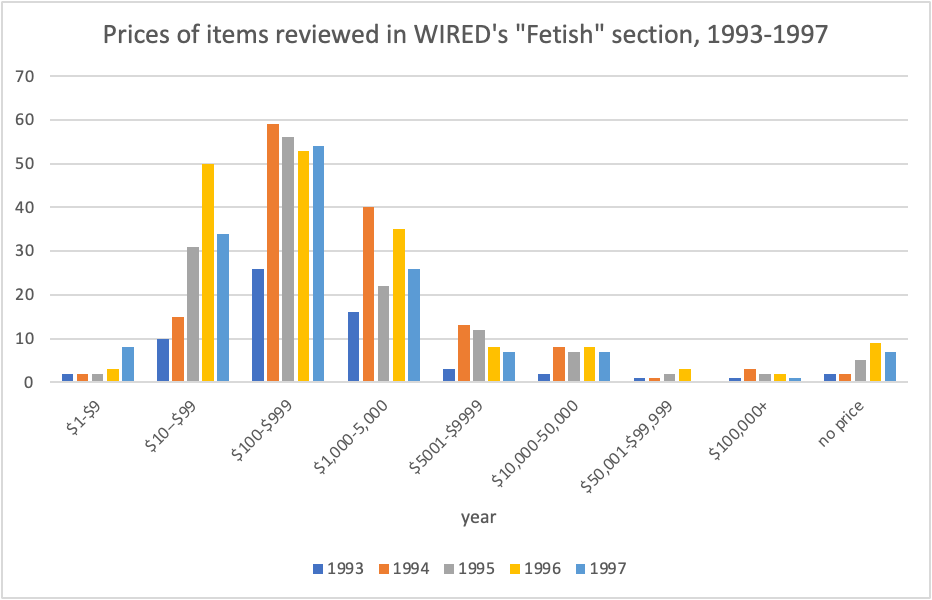

Fetish went through four editors during its first five years — Frederick E. Davis, David C. Jacobs, Tim Barkow, and Bob Parks. Each brought their own sense of style and flair to the section. Jacobs took over in May 1994, and was the zaniest of the bunch. He, um, was just really into watercraft? Take a look.

…Yeah, that’s a personal submersible. “One of the few places on earth where you can escape the tourist hordes is the ocean floor. (…) If you want to extend your voyage to the bottom of the sea, try the C-Questor, a fully submersible vehicle that looks more like a sci-fi space pod than a personal submarine.” Price: $85,000. Who, I ask, is this supposed to be for?

These gaudy, over-the-top product reviews weren’t quite frequent enough to be a running joke. In one issue, they would review a helicopter or speedboat. In the next issue, the most expensive item would be a nice projector for powerpoint presentations.

What strikes me about many of these reviews is the aspirational audience that they are trying to will into being. WIRED is painting a picture of the emerging “netizen” as a market segment that loves cutting edge technology (fetishizes it, even) and is flush with cash. Setting aside the gaudy outlier items, the typical $1k-5k reviews were for high-end projection equipment and aeron chairs. The $5k-10k reviews were for desktop and laptop computers, or deluxe photocopiers.

The review section is clearly influenced by Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalog. Kevin Kelly, WIRED’s Executive Editor, had worked closely with Brand on the Whole Earth Review. Nearly all of WIRED’s original writers listed email addresses from the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link. But where Whole Earth was the bible of the 1970s back-to-the-land movement, these WIRED reviews are unmistakably suffused with 1980s yuppie culture. They are intended for corporate managers and comfortable 1%ers who are in the market for the best speaker system money can buy.

I don’t have a sense yet of when WIRED’s review section turned into an actual product review section. That comes much later — either in the ‘00s or ‘10s — once tech culture has become less aspirational and melds with mass culture.

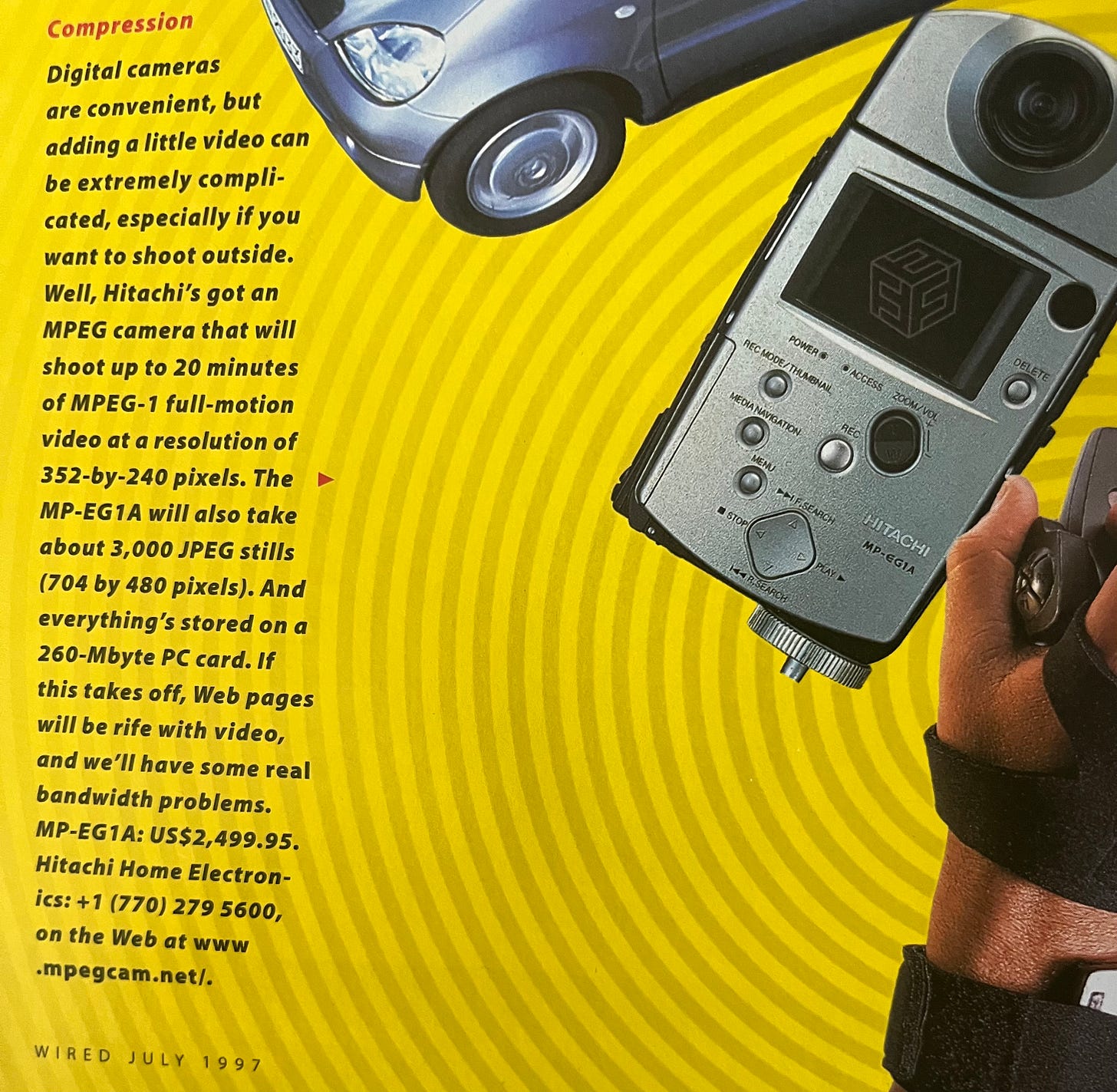

Setting aside the brash, comically expensive items, I was also struck by the implicit story the other product reviews tell. Take a look at the July 1997 review above: a digital video camera, capable of shooting up to 20 minutes of full motion video. “If this takes off, Web pages will be rife with video, and we’ll have some real bandwidth problems.” Price: $2,499.95.

It did take off. We dealt with the bandwidth problems. Eight years later, we got YouTube.

But the digital video cameras supplying a steady stream of YouTube content didn’t cost $2,500 apiece. They cost a few hundred bucks. And they worked much better than this early, pricey model. That’s Moore’s Law, in a nutshell — The constant doubling of processing power and halving of price.

Gordon Moore’s original prediction was about transistors and silicon wafers, back in the era of mainframe computing. Moore’s Law was not a prediction about consumer electronics product lines. But in the 1990s, and lasting through the 2000s, consumer tech was changing so fast that it felt like Moore’s Law was happening everywhere.

You could be an early adopter and buy a video camera in 1997 for $2,500. Or you could wait five years and buy a superior model for 1/4 the price. The laptops and desktops advertised in 90s WIRED cost $3,000-$7,000. (To adjust for inflation, you can basically double those numbers.) A few years later, those top-of-the-line machines could barely run the latest MS Office package.

I’ve written previously about how Moore’s Law has come to function less as an empirical claim than as an ideological commitment, and about the slowdown of Internet Time. Its going to be one of the big themes in the book.

Reading the old product reviews, what really hit home was how real Moore’s Law felt back when consumer technology was changing so rapidly. You could buy an $8,000 flat screen TV in 1996, or you could read about it in FETISH and just wait a few years for the better/cheaper model. Last year’s unattainable conspicuous consumption is the next year’s Christmas gift.

That consumer-level experience ended in the early ‘10s, I think. I haven’t quite nailed the date down yet. Today’s new iPhone costs basically the same as your last iPhone. It has a faster processor and better screen resolution, but not so much that you would notice. A good laptop can last a decade, and most of us won’t much notice the difference when we replace it with the latest model.

I lived through those years. It’s been long enough that, on some level, I had forgotten about them. It’s a nice reminder of why, in the web 2.0 era, I was pretty well convinced that the pace of Internet Time was changing everything and would never slow down. It wasn’t a fundamental social transformation. It was just a decade or so in the history of fancy gadgetry.

But that’s too serious of an insight to end on. Let’s end instead with the biggest pricetag in the dataset: a $75,000,000 yacht-submarine hybrid.

“What to do when the novelty of one’s yacht wears off? Take the plunge beneath the waves, of course. U.S. Submarines Inc. produces a range of luxury submarines for the absurdly rich. Relative paupers will have to make do with the Discovery 1000, a four-passenger minisub, while the truly well-to-do can opt for the the Phoenix 1000, a submersible megayacht of palatial proportions.”

REMINDER: all megayachts are submersible if you try hard enough.

"Wait, it's all (consumerism)???" "Always has been"

What these WIRED product "reviews" remind me of are the reviews and ads in Playboy magazine in the late 60's/early 70's, the era of my maximum interest in the content (great interviews). They were an attempt to get the reader to imagine the kind of swinger he could be with the right clothes, car, stereo, alcohol. Even if you couldn't afford it on your allowance, you knew about it so you could speak authoratively to your friends about the Testarossa or McIntosh power anp for your stereo.