From the WIRED archives: The trajectory of any emerging technology bends toward money

A peek at some tech predictions from January 2000

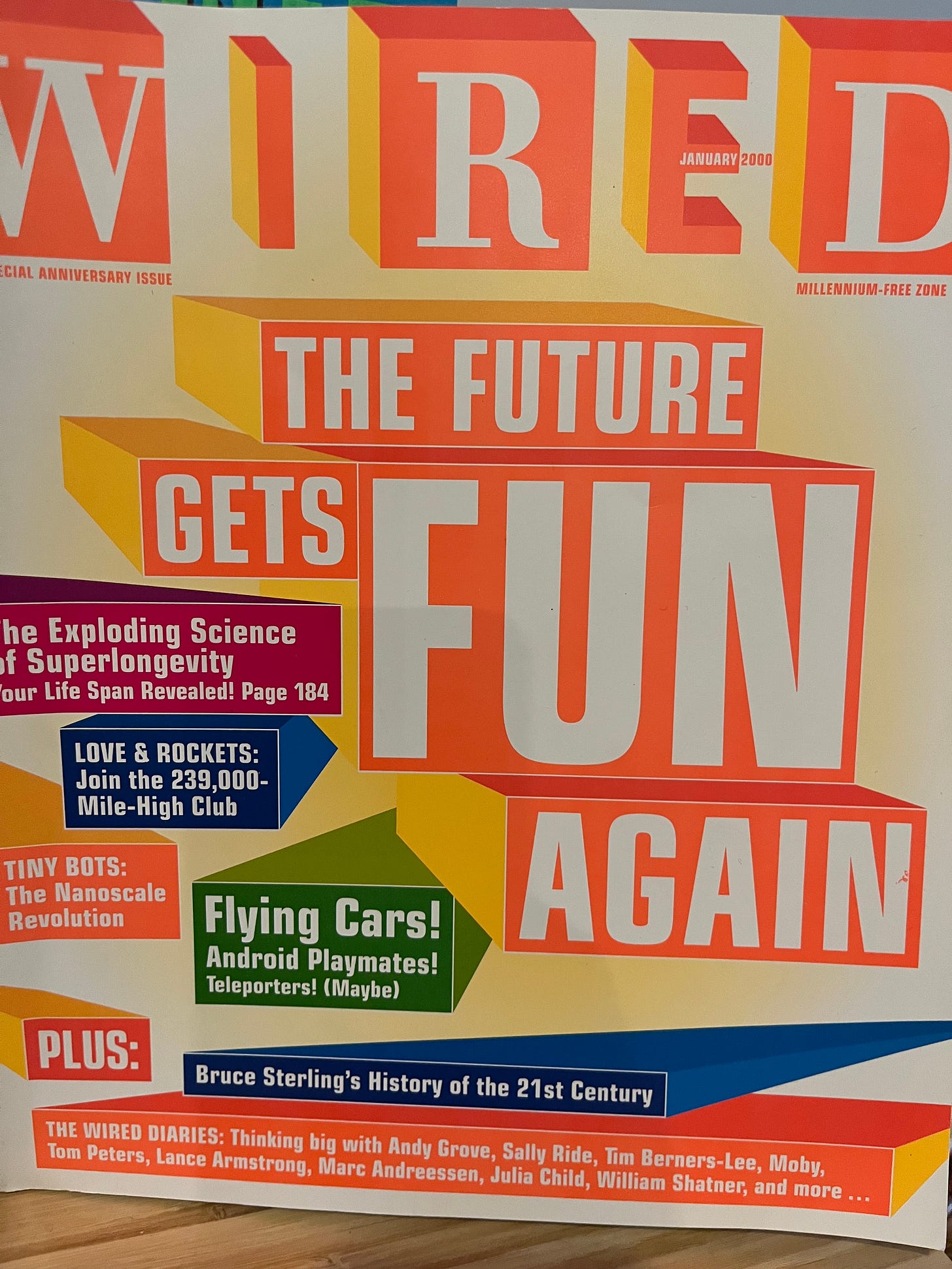

Today I just want to share-and-shout-about a few lines from the January 2000 issue of WIRED magazine.

(Context: I’m reading the entire WIRED back catalog chronologically. It’s part of a book project on the “history of the digital future.” If you’re curious, you can read about the book project here, and/or read the 2018 article I wrote for WIRED about the other time that I read the entire back catalog chronologically.)

.The January 2000 issue is themed around predictions. The magazine did the same thing in January 1999. They ask a ton of experts and celebrities to talk about what the future is going to be like. Some take it seriously, others make jokes. Some are prescient, others notsomuch. It’s a window into what the future looked like back then.

There are some particularly crisp lines in this issue.

-There’s Eric Schmidt (back before he joined Google), saying “In 2040, I think my primary concern will be life extension. Baby boomers as a group are going to be obnoxious old people because we’re used to getting our way.” (Too true, Eric. Too true…)

-Bruce Sterling also delivers a proper cyberpunk warning: “I expect science to be conquered by market forces just like the Internet was, so that science becomes indistinguishable from product development. There will still be a few guys in ivory towers pursuing basic questions, but they’ll be regarded as arty cranks who have outlived their time. This should mean that quarks and neutrinos are forgotten, while we get consumer toothbrushes as complex as cyclotrons.” (Read Mariana Mazzucato’s 2015 book, The Entrepreneurial State, to see how right Sterling ends up being…)

-Professional Skateboarder Tony Hawk makes a cursed monkey paw-wish: “There should be an archive of every show that’s ever been on. And then anything else that you desire to watch, including security cameras from any part of the world.” (Good news/bad news, Tony: The future is going to include both Netflix and Ring. But capitalism is going to reveal some, uh, downsides to each.)

…And then there’s this perfect Nathan Myrvhold quote “There won’t be TV per se in three decades. There will be video service over the Internet, but it will be as different from TV today as, say, MTV from the Milton Berle show of the 1950s or from radio plays of the 1940s.”

This is art. I want to frame Myrvhold’s quote and put it in a museum of lopsided tech futurist predictions.

The part that he gets right is the technological development curve. There he is, at the turn of the millennium, five years before the inception of YouTube, telling us that the future of television is going to be video service over the Internet. Yes, absolutely right!

But the part he gets wrong is the industrial, social, and economic impacts of this technological development. We’re seeing this right now, in 2023, as the various streaming services add advertising and strike content-sharing partnership deals with each other. We have these revolutionary new technological developments, and, for about a decade, they were supported by a stock market bonanza. But now that the stocks are no longer ridiculously overvalued, the companies driving these technological developments have settled on a vision of replacing old cable tv with new cable tv. (I wrote about this in July 2022, btw, back when this Substack had a much smaller readership. I think the piece holds up well.)

Technologically, it didn’t have to be this way. But, given all the existing incentive structures established by 21st century capitalism, it was all-but-certain that we would end up here.

I see this time and time again when reading predictions of social transformation from 90s- and 00s-era technologists [*cough* NicholasNegropontewasconstantlywrong *cough*]. And I see the same thing today, every time an artificial general intelligence true believer starts opining on the glorious future of education/entertainment/science/manufacturing/art.

I wrote about this phenomenon last year in The Atlantic, where I argued that we won’t be able to tell what the future of AI looks like until we have a sense of where the revenue streams come from. The trajectory of any emerging technology bends towards money.

I imagine the VC class and the dotcom futurists must know this, on some level. They are in the business of making money, after all. And yet, when they talk about the future, the gravitational pull of potential revenue streams is always edited out.

Technologically, we could by now have an archive of every single show that has ever aired. Except no, of course we couldn’t. There isn’t nearly enough money in that.

And look, yes, all of this fits comfortably within Cory Doctorow’s “enshittification” framework. Enshittification is inevitable under the currently-dominant version of capitalism. The capitalists (surprise, surprise) edit that out of their grandiose predictions about the technological future. I won’t claim I’ve found something fantastically new.

But oh, the receipts. Would you look at these receipts!

I’m writing a whole book about the lopsided ways in which tech futurists always get their predictions wrong. And one major reason why is that they focus on what the technology could do, given time and mass adoption, rather than considering what capitalism will surely do to those technologies, unless we alter the incentives through regulations.

The trajectory of every emerging technology bends toward revenue streams. If you want to build a better future, you cannot ignore the shaping force of money.

"The trajectory of any emerging technology bends towards money" — I wish I had had that insight so clearly much earlier.

"[*cough* NicholasNegropontewasconstantlywrong *cough*]" — LOL. So true. I liked Steven P. Schnaars' book "MEGAMISTAKES: Forecasting and the Myth of Rapid Technological Change" where he gives the telling example that in the 50's and 60' the new technologies on everybody's mind were 'the jet engine' and 'TV'. And of course, the solutions/predictions heavily featured these. For instance, people proposed to improve education by putting TV transmitters in jet engines so that every child could be taught by the best teachers. That solution wasn't proposed because it worked (it wouldn't have) but because these dominant new technologies were part of the Zeitgeist and coloured everything. So, when the internet was on the rise in the 1990s, we got the internet proposed as (simple) solution for everything, from democracy to education. And we got people arguing that 'the internet' had become intelligent/sentient. Etc. And now AI. Sutskever: "AI will solve all the problems we have today. It will solve employment. It will solve disease. It will solve poverty".

Humans and their intelligence/convictions, are a far more fascinating subject than the content of those convictions.

A couple of years ago, during the height of the streaming bonanza, I kept saying that the economics made no sense except as a stock market bubble, and that the minute that receded, the status quo would return to the mean of ad-supported broadcasting. It has been something to watch everyone who once argued with me over this slowly come to grips with it (when Netflix announced ads last year - something which appears to have more or less saved their business singlehanded - every thinkpiece treated it like a novel plague instead of just how commercial television invariably works)

One aphorism I would also add: you can't solve social or cultural problems with technical fixes. Something like Netflix was perfectly happy to let creative and consumer alike believe that they had a genuine interest in improving our media infrastructure for the better and more adventurous, right up until the buck stopped. Commercial mediums don't change their stripes no matter how novel the distribution strategy is - instead of trusting a for-profit corporation to invariably do the right thing, you would've been better off dramatically overhauling public broadcasting so that it's finally something more than the perpetually starved, pledge-dependent appendage it's been since Nixon.