Bullet Points: OpenAI looks for its FarmVille, 90s tech nostalgia, and more on the Substack drama

Hi everyone,

I’ve got three items to share, none of which merits a stand-alone post. So it’s time for another edition of Bullet Points, where Dave just talks about a bunch of stuff!

Today: OpenAI is looking for its FarmVille, 90s tech nostalgia, and more Substack drama!

(1) I have a new piece at TheAtlantic, discussing this week’s launch of OpenAI’s GPT Store. It seems like this launch has flown under-the-radar a bit. Sam Altman made a big deal about it back in November. Then, two days later, all the drama happened. The launch of the store was pushed back a couple times. OpenAI says that, in the interim, users developed over 3 million custom GPTs. Now it’s marketing those GPTs, trying to turn itself into a platform.

The thrust of the piece is that this all has a pretty strong Facebook-in-2007 vibe to me. Facebook’s main strategy in the late aughts was to invite third-party developers to create apps that would run within Facebook’s walled garden. The biggest success was FarmVille, but the whole endeavor was crucial to expanding Facebook’s footprint during those transition years when social network sites were becoming social media.

Altman, like Mark Zuckerberg before him, has imperial ambitions. Zuckerberg aimed to colonize the internet, remaking it in Facebook’s image. He largely succeeded. Altman’s ambitions are even larger. And so, like Facebook, his company has reached the point where it is hoping someone else can develop the next wave of use cases. He’s attempting to turn it into a platform.

The article is titled “ChatGPT’s FarmVille moment.” I think it’s a good one. Please check it out.

(2) I want to briefly respond to Om Malik’s essay from earlier this month, “Is Optimism Wired or Tired?” Malik has been a tech writer since the glory days of the 1990s. And the basic argument of the article is that the vintage Wired optimism of 1995 is something that tech publications are desperately lacking today. He writes:

“When I think about optimism, I wonder what is the role of media, particularly the technology media. Wired is a perfect example. It was a magazine that often gave us context for the future and all the technologies that were coming our way. It presented a scenario that inspired and gave us hope. Today, when you look through the magazine, it feels like just another run-of-the-mill magazine, that is focused on highlighting the dark side of technology and all the havoc it’s going to wreak on the world.”

I hear this argument a lot from folks who have fond firsthand memories of the 90s tech boom. And, as longtime readers of this blog can surely surmise, I find the nostalgia sociologically interesting but substantively unpersuasive.

First of all, go back and read the first few years of WIRED and compare it to the past few years of WIRED. Yes, there were some bright spots in those glory days. The magazine had cachet. It was a trailblazer. And that has dissipated as the rest of the tech press caught up. But it was also so uneven. The writing today — the acts of journalism the magazine is committing — is better than it was back then, full-stop.

The thing I keep wondering with articles like this is: are the writers nostalgic for the tech journalism of 1995, or for 1995 itself?

1995 was still, in so very many ways, the before-times. Silicon Valley was small but growing. Engineers were becoming millionaires. (Millionaires!) Rent in San Francisco was cheap. The Cold War was over. Capitalist democracy had defeated Soviet communism. It seemed there were no more enemies left to fight, no nuclear missiles pointed our way. We were going to have a global culture, networked together through the magic of Moore’s Law. It all seemed like everything was going to work out. And, also, the authors themselves were young. I am nostalgic for the 00s in much the same way Malik is nostalgic for the 90s. That’s not because I miss the Bush years. It’s because I miss (select parts of) being in my 20s.

The lack of optimism from the tech press (which, btw, is a debatable proposition. Take a look at how mainstream tech reporting covered the Metaverse and Web3 in 2022 and tell me with a straight face that lack-of-optimism was the problem) isn’t because they have grown jaded or fearful. It’s because, as Marc Andreessen(‘s ghost writer?) so memorably put it, “software ate the world.” The companies and Venture Capital networks that make up Silicon Valley became the center of the global financial system. The techno-optimists (like Andreessen) won. And their victory didn’t turn out anything like the 90s tech coverage envisioned.

Malik seems to recognize elements of this. He realizes that things are bad right now, and the tech companies he cherishes are often at the center of things. But he still insists that the same optimism that inspired him in 1995 is what is necessary today.

I don’t buy it. I think beginning from a position of optimism, rather than pragmatism, is a mistake. I am convinced that we were not well-served by the optimism of the 1990s, because that optimism was a political project. It was aimed at warding off regulation and taxation to the benefit of Silicon Valley elites, and it succeeded. Things would have gone better, I suspect, if we had not been so confident that the best way to build the future was to keep everyone-but-Silicon-Valley quiet and cheerful while the engineers and entrepreneurs worked things out for the rest of us. I think we would be ill-served by a return to that long-dominant status quo today.

But I also can’t shake the feeling that, when these writers argue for a return to the golden days of the 90s, what they’re really saying is we should return to their golden days. I missed out on the early dotcom tech scene. I’m sure it was great for those who lived through it. But it isn’t something we can actually return to.

Instead of grousing about tech magazines these days, I wish these guys would just hold a reunion with some old friends. There’s nothing wrong with cherishing the way-things-were. It just doesn’t make for a compelling critique to the way-things-are-now.

(3) Some additional Substack thoughts.

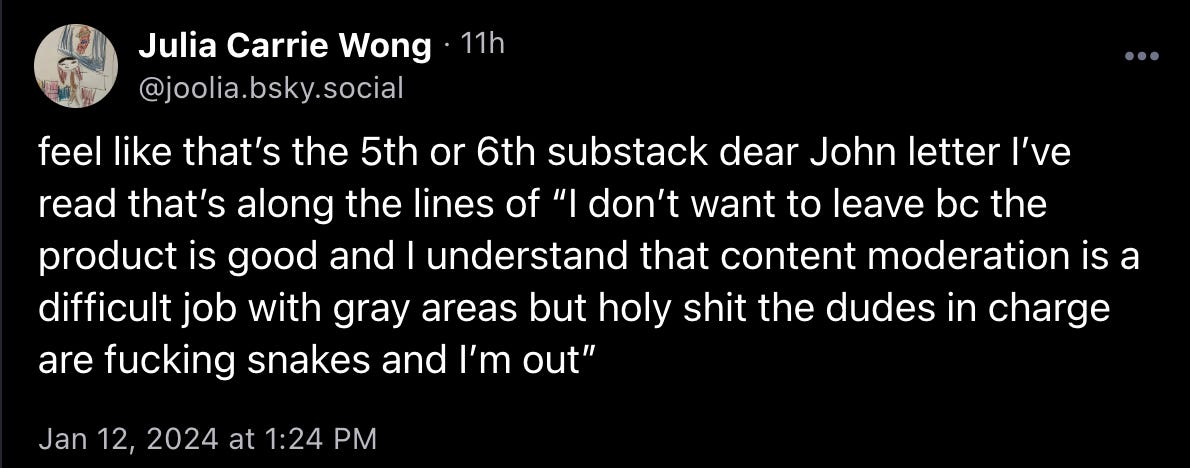

Well, this week certainly hasn’t gone well for ye olde newsletter provider. Casey Newton’s Platformer is quitting Substack. So is Ryan Broderick’s Garbage Day. Same with Popehat, and Jonathan M Katz’s The Racket, and Paris Marx’s Disconnect, and Molly White’s Citation Needed, and and and… well, you get the idea.

It seemed on Monday night like Substack had finally taken the small, positive crisis comms step it needed to take in order to quiet this down. They had tried ignoring the problem. They tried doubling down on an untenable position. They had tried framing the problem with strategic leaks to Michael Shellenberger. (Strategic communication pro-tip: if one of your main tactics is “rely on Michael Shellenberger,” go ahead and set that strategic plan on fire and start with a fresh sheet of paper. You have made multiple errors of judgment and the plan is not salvageable.) They finally tried some basic crisis comms by saying “ah yes, we see now that these are NAZI blogs. Those are indeed in violation of our existing policies. We’ll be removing them. Thank you very much for bringing this to our attention. We messed up here. Content moderation is tough. We will be more responsive and proactive in the future.”

The immediate problem they ran into was that, well, they didn’t exactly say “yes this violates our policy, we see that now, whoopsourbadwonthappenagain.” They said something more along the lines of “okay fine we’ll take down five of the very worst ones. But you see how this was a non-issue all along, right? Anyway, we’re not going to change anything, but you’re welcome to send us notes flagging other *literal nazi newsletters* that you find in the future.”

But the larger dynamic, and this is the point I actually want to dwell on for a bit, is that all of this nonsense runs counter to Substack’s central value proposition.

There are basically two versions of Substack. There’s the free version, which is just a blog with an email distribution list stapled to it. And there’s the paid version, which promises a toolset for writers to build their own audience and make a living from their craft, without having to depend on the wreckage that is the existing institutional media landscape in the 2020s.

The free version is nice. It’s simple. The blogging software does all the stuff you need it to do. The email list is a marvelous replacement for Google Reader (R.I.P.). The basic analytics provide a dopamine hit (“hey, people actually read what I wrote. I’m not just shouting into the void. That’s cool!”). But the free version is also, y’know, free. You can’t build a business off of free. (with apologies to Chris Anderson… that prediction didn’t age so well!)

The paid version was what, for a little while, let Substack adopt the aura of the Future of Media. Because the future of institutional journalism and so many other forms of established media seems bleak. And here was an upstart that would let you become your own media company. It was Kevin Kelly’s “Thousand True Fans” theory made real, for all kinds of writers.

The promise of that paid model (the one that Substack could turn into a viable business) was: we’re going to make this easier for you. The tools are simple. We’ll build out additional features. There will be recommendations and network effects. Fundamentally, you will get to bet on you. We’ll be in the background, helping everything to run smoothly.

And the problem over the past month has been that the Substack founders keep fucking up in ways that impact those writers’ livelihoods.

This is the underlying point of agreement between Casey Newton’s and Ryan Broderick’s announcements that they’re leaving and John Ganz and Paul Musgrave’s (earlier) announcements that they’re staying. All of them share a frustration that boils down to “fuuuuuuck… I’ve worked really hard to build this thing, and now I have people who have supported my work deciding they will no longer support it because Chris and Hamish can’t shut their fucking mouths or just say “sorry, we’ll try harder in the future” like any other platform!

This was the dynamic I was dancing around in my December 14 post, “On Substack Nazis, laissez-faire tech regulation, and mouse-poop-in-cereal-boxes.”

The correct amount of white nationalist newsletters on this platform is not exactly zero. That’s practically unworkable. But it’s approximately zero. There should never be more than trace amounts of internet Nazis on a big publishing platform with ambitions for becoming bigger. Once you have enough internet Nazis that readers and writers can notice, it’s time to put resources into cleaning the place up some more.

Left unsaid there was “if you have enough internet Nazis that it becomes a story, then your platform is getting in the way of your writers’ ability to make a living. That will ultimately be bad for your business. Fix it, dummies.”

The problem with the laissez-faire approach to content moderation isn’t just that you end up becoming the proverbial Nazi Bar, and then your writers have to decide if they want their own newsletters on the platform. It’s that your value proposition was “bet on yourself. Build an audience. We won’t get in the way.” And once you start defending the literal Nazis on the platform, you have gotten in the way.

This is also why the sheer incompetence of their communication strategy grates so hard in this case. Because it sure can’t inspire confidence among the writers who are trying to make an actual living through their writing on this platform. Like “oh cool, you screwed up the literal internet nazi moderation problem so much that it became an international news story. I wonder how many subscribers I’ll lose the next time you face a very simple communications challenge.”

It’s one thing to have a platform that rolls out underwhelming social features, or takes a relatively hands-off approach to content moderation. (There are, uh, a lot of companies with those issues.) But it’s another thing to directly cost your writers the audience they worked to build. Because not-doing-that was the core value proposition all along.

(It’s a bit like having committed to eat all your meals at a restaurant that keeps failing health inspections. Maybe they serve your favorite meal, and you’re friendly with the owners from way-back-when. But that’s still a bad commitment! It won’t go well for your long-term health! Why would you keep doing that? There are plenty of other restaurants!)

The part that I find especially interesting here is how the two models (paid and free) influence the calculus on when and whether to leave for another newsletter service. Paid Substacks have much more on the line, and much more to lose. But they also are getting much stronger signals from their readers. (And, frankly, it sounds like the other newsletter services charge less than Substack’s 10% cut for those with a large readership.)

Free Substacks, by contrast, have less to lose by switching, but also (a) are choosing between paying Substack nothing versus paying another service something (ugh. That’s a drag.), and (b) are receiving weaker signals through their analytics. I’ve lost some readers since this whole episode started, but I don’t have a clear signal whether that’s because they refuse to subscribe to Substacks anymore, or they’ve gotten tired of my writing in general, or they specifically disagree with how I’ve approached the topic. It isn’t a huge dropoff in readership, so it’s likely some mix of the three. …And, more importantly, this is just a blog stapled to an email distribution list. The time I spend checking the analytics dashboard is time that I should probably be working on the book manuscript instead.

I suppose that’s also all a longwinded way of saying that I still have nothing to announce yet regarding imminent departures. I figure I’ll stay put on this platform until the book is drafted. I’m a little worried that their finances will collapse and the whole thing will go up in flames, so I might get antsy and move sooner. But I would like to focus on writing the book, continuing to maintain this free blog on the side, and hold off any decisions about next steps for my writing until I have a draft. If those next steps include adding a subscription tier, then I’ll likely move to beehiiv or buttondown or ghost.

I am optimistic that this will be the last post I write about Substack management for a good long while. I find I have a lot to say on this topic, since it sits at the intersection of tech platforms and strategic communication… basically all of the classes I teach. But also, yeesh, aren’t we all getting tired of this?

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll be back soon with some proper deep dives into the lessons we ought to learn from discarded digital futures’ past.

Best,

DK

There are actually three versions of Substacks. The two you mention, free and paid, and a third: a free or paid newsletter with Notes.

If Substack was just a platform that hosted your newsletter/blog/site, like WordPress or Blogger or Squarespace or Wix or Weebly or Buttondown, writers on the platform wouldn't even notice who else was on the platform (besides the people they read). But no, you can't just be a writer on Substack you have to be a SUBSTACK WRITER (TM), marinating in Notes (which has become more like Twitter than people will admit) and liking this and that and recommending and getting badges and stars and hearing from the CEOs all the time and being part of the "writer's community." Sigh.

More here:

https://sassone.wordpress.com/2023/09/28/we-need-to-talk-about-substack/

Thanks for this. In keeping with the Bullet Points approach, two things. Your FarmVille point reminds me of how undependable the big platforms have been for ISVs over the decades. VCs learned the hard way not to invest in software companies that were single-threaded on any one platform (Microsoft, for example, back in its server days) as those platforms could and did change their API and partner policies (we like you! we'll buy you! we'll crush you!) on the fly. On your substack point -- see the above. Platform volatility is as great today as it's ever been. But we have a much more broadly distributed creator economy than before ... so platform earthquakes affect a whole lot more folks , quickly. I wish there more coverage of the 'long-tail' of substack users who eke out an audience and maybe a little dosh and really can't afford the time, tech capability, or money involved in switching platforms. Platform volatility has been around since .. platforms .. just hurts a lot more a lot harder, now.