The Hollow Core of Kevin Kelly's "Thousand True Fans" Theory

The creator economy is not good, and it's getting worse.

To be a successful creator you don’t need millions. You don’t need millions of dollars or millions of customers, millions of clients or millions of fans. To make a living as a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor you need only thousands of true fans.

This is the opening passage from Kevin Kelly’s 2008 essay, “Thousand True Fans.” Kelly is one of the defining techno-optimist voices in the history of the internet. Among other roles, he was WIRED magazine’s founding Executive Editor (meaning I have read a whole lot of Kevin Kelly at this point). Thousand True Fans might be his most iconic, beloved piece of writing.

Thousand True Fans is a rallying cry for our current podcast/youtube/Substack economy. Kelly declares that the digital revolution has made it more possible than ever to find your audience, build a relationship with them, and make a good living doing something you love. As media organizations go through round-after-round of layoffs, Thousand True Fans tells us that a better world is possible if we just believe in ourselves, trust each other, and embrace the wonderful opportunities the internet provides.

I certainly don’t begrudge the digital creators who take inspiration from Kelly’s essay (it’s tough out there, take solace where you find it). But it troubles me how popular this essay still is, almost fifteen years after it was first published. I think Thousand True Fans is ultimately hollow. It’s a band-aid, masquerading as a miracle cure.

I think we ought to take Thousand True Fans seriously because of the people who are still loudly promoting it today. Chris Dixon, the a16z venture capitalist who is both Web3’s biggest promoter and largest funder, turns to Thousand True Fans to scaffold his claims that that NFT sales will be the future of music. He’s convinced himself that the best way to support writers, musicians, and artists is to turn the entire internet into a financialized gambling instrument (where he and his fellow VCs just happen to be the casino).

So I want to take a closer look at how the story Kelly tells holds up today, almost 15 years after he first wrote it. And I think we should pay particular attention to the normative work his essay does — both the characters that it centers and the perspectives and possibilities that it ignores.

The Cliff’s Notes version of Thousand True Fans goes something like this:

Thanks to the Internet, there has never been a better time to be a creator/writer/musician/artist.

All you need to do is find and cultivate a thousand true fans. A “true fan” is someone who will spend $100/year supporting your work (That’s like $8.25/month). With a thousand of them, you would be making $100K per year doing what you love!

This is premised on developing a “direct relationship” with your fans. They pay you directly, with no music labels, publishers, studios, retailers, etc taking a cut. The web means we don’t need these old intermediaries anymore.

And these fans can find you without those old institutional intermediaries, thanks to the “Long Tail” effect (as defined by another major WIRED figure, Chris Anderson).

So you don’t have to aim for a million fans in order to succeed. It isn’t stardom-or-bust. That’s too high of a bar to aim for. A thousand true fans won’t make you rich and famous, but it’s a realistic way to make a living doing what you love.

You can likely see why Kelly’s essay became so popular. He’s basically sketching the territory that would later be filled by Kickstarter, Patreon, Substack, etc. He’s also approximately predicting the rise of digital influencer-hustle culture. And he writes in a way that encourages people to take that career-leap that they’ve been thinking about taking. What could be wrong with that?!?

On closer examination, it turns out there are many things wrong with it. Thousand True Fans is a hollow philosophy. It is Chicken Soup for the Digital Creator's Soul, ultimately devoid of any real nutritional value.

Problem 1: The Long Tail was only half-right.

Thousand True Fans is Kevin Kelly’s riff on Chris Anderson’s Long Tail thesis. And the Long Tail idea turned out to be only half-correct.

Anderson observed that digital distribution removed the artificial limits imposed by scarce physical space. Tower Records can only house the CDs that fit within a given store’s square footage. Borders Bookstore has scarce shelf space. But the iTunes store has limitless storage, offering listeners access to basically every song ever written for $0.99 apiece (at the time, with a few key exceptions). Amazon can give you access to absolutely everything, even if it’s self-published.

He was right about that initial observation. The move from atoms to bits has radically changed how consumers find and access all forms of media.

But Anderson then inferred that companies were finding there were more fans, and more potential revenues, in the “Long Tail” of small subcultural niches than in the “Short Head” of mega-hits. If you tally up all the songs on iTunes that only get 10, 100, or 1,000 downloads, you end up with more than all the chart-toppers combined. So Anderson argued that the future of the internet would be niche media.

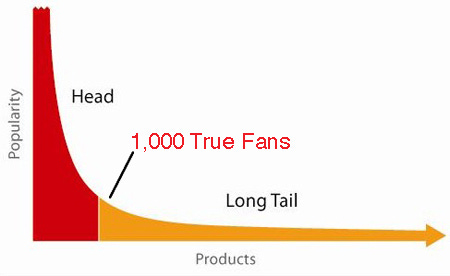

Thousand True Fans draws heavily on this inference. Kelly illustrates his essay with the graph below:

In Thousand True Fans, Kelly writes, “A fundamental virtue of a peer-to-peer network (like the web) is that the most obscure node is only one click away from the most popular node. In other words the most obscure under-selling book, song, or idea, is only one click away from the best selling book, song or idea.” This is only true when the peer-to-peer networks are small, though. As the network gets bigger, the platforms develop algorithms to help people discover what they are looking for/what they want but might not be looking for yet. It results in a power law/rich-get-richer phenomenon, driving attention and audiences toward the biggest successes and away from the niches.

What we’ve mostly experienced with the Internet of the past fifteen years is that the platforms algorithmically funnel everyone’s attention to the same thing. The blockbuster hits have gotten bigger than ever. The niche players, for the most part, still struggle.

(We’re also less disintermediated than Kevin Kelly thought. Thousand True Fans is premised on the assumption that you can develop a direct relationship with your “true fans.” That rarely turns out to be the case, though — iTunes and other digital distributors take a 30% cut of everything sold on their platforms. Spotify replaced iTunes as the go-to music platform, and they pay in fractions of a penny per stream.)

The reality is that there’s a lot less money and attention in the niches than we thought back in the heady days of Web 2.0. It’s harder to attract the attention necessary to get a thousand paying supporters than the Long Tail led us to believe. The culture industry still bends toward the big hit-makers.

Problem 2: Who gets to be a “True Fan,” anyway?

There’s a class and status bias lurking underneath the Thousand True Fans idea. Not everyone has a hundred bucks per year to spend on each of their hobbies.

The ideal “True Fan” is someone with enough money that they can effortlessly become a collector of anything that appeals to them. As wealth inequality gets more extreme, the gap between the collectors and the plebes just keeps growing.

We can see this with Web3 and NFTs. Last month, Gary Vaynerchuk made a prediction that “in a decade, [our airline tickets] will become micro collectibles because they will have an artist attached to it. And somebody may offer you $280 for a flight that you took from Bucharest to Mykonos because they follow that artist.”

That’s a real True Fan: someone willing to shell out $280 for the digital receipt from someone else’s airline flight because it is connected to an artist they like.

That’s also, let’s face it, definitely someone who works in tech and/or finance.

As a practical matter, Thousand True Fans is going to work out best if your music/art/writing caters to the tastes and preferences of the wealthy.

So if you are an aspiring tech optimist thought-leader, and if you hustle real hard, attracting the type of super-fans Kevin Kelly is talking about, then you really only need a thousand or so. Offer insights that appeal to entrepreneurs and VCs, and you open up opportunities for speaker’s fees and consulting gigs. Play to the crowds that are used to seven-figure entertainment budgets, and you really don’t have to work too hard to earn $100 apiece.

But if your art or your journalism heads in a different direction, it’s going to get a whole lot harder. Speaking honest, uncomfortable truths to power has never really been a profitable business model.

An alternate path is to specialize heavily in internet drama. Charlie Warzel reflected on this point when he moved his newsletter from Substack to The Atlantic. He was reasonably successful on Substack, but could never compete with the top-tier Substackers because, among other things, he “never did enough grievance blogging” and he failed to get into the kind of arguments that go viral on Twitter.

If you think about the podcasters, YouTube personalities, and Substackers who have really succeeded, most of them engage in a ton of messy internet drama. There are some rare exceptions (Heather Cox Richardson). But the attention dynamics all bend toward internet drama.

If I wanted to turn this Substack into a successful subscription product, I know exactly what I would have to do to get my Thousand True Fans. Every week, immediately after Bret Stephens publishes a new Op-Ed, I would write a scathing take-down of his latest work. It would be a Bretbug dunk-a-thon, complete with Bretbug merch and subscribers-only MST3K-style videos where I heckle Bret anytime he makes a tv appearance. It would be soulless, and it would be a little-too-mean. But it would capitalize on my one moment of internet-fame, and (judging by how much more popular my Bret Stephens tweets and posts are than anything else I write), there is probably a niche audience that would pay for that stuff.

When Thousand True Fans was written in 2008, influencer culture wasn’t a thing yet. Kevin Kelly can be forgiven for not realizing that we would all become monsters in service of the like and subscribe buttons. But, with the benefit of hindsight, this is one of the most glaring absences in the essay. You may not have to sell your soul to the record label or publishing house. But there are still tradeoffs and sacrifices as you chase the people who will actually pay.

Problem 3: Wealth inequality is making everything worse. Thousand True Fans is not a solution.

I get a strong #okayboomer vibe every time I read Thousand True Fans.

Let’s grant the premise for a moment that, if you really hustle and pursue your artistic passions, you might eventually develop a fanbase where a thousand people pay $100 per year to support you. You’re making six figures doing what you love. Congratulations.

But now let’s layer in some costs. You’re self-employed, so you have to pay an additional 15% on top of the normal income tax rate to cover Social Security and Medicare payments. You’re also going to have to buy your own health insurance. If you live in a major metropolitan area, the rental payments have reached nosebleed levels. Even if you make it, you’re probably living with roommates for a long, long time. You’ll never save up enough to afford a down payment on a house. (And let’s not talk about those student debt payments.)

In 2022, a Thousand True Fans probably just isn’t enough. And, unless we rein in housing costs and student debt payments and wealth inequality, it’s just going to keep getting worse. It’s a recipe for running the Red Queen’s Race, moving faster and faster just to stay where you are.

This isn’t to say that $100K doing something you love isn’t a much better situation than the vast majority of jobs out there. Of course it is. But this isn’t a salaried job offer we’re talking about here. This is the dream. It’s the ambition. (…The dream scenario should probably result in you being able to eventually buy your own place, right?)

The Baby Boomer generation had access to cheap higher education and cheap home ownership. It was a sweet deal; one that they seem to have generationally taken for granted. And I can’t help but read those generational assumptions into the things-left-unsaid by Kevin Kelly’s essay. If you have the stable footing of generational wealth, then Thousand True Fans is a great deal. But without that stable footing, it’s a recipe for precarity. Thousand True Fans is an essay that celebrates a type of freedom that only the already-well-off can really enjoy.

(Kevin Munger’s book on how the internet exacerbates generational divisions between Baby Boomers and Millennials is great, btw.)

Problem 4: The Bigger Picture

What bothers me most about the Thousand True Fans concept today is how I see it being deployed by the Web3 crowd. Chris Dixon and his peers are convinced that the only reason Web 2.0 platforms failed to usher in a golden era for internet creators was that the “take rate” from Apple and the other platforms was just too high. Their solution is to build a new, even-more-financialized internet (as Ian Bogost writes, “The Internet Is Just Investment Banking Now”). And that just so happens to be an internet where wealth inequality gets a lot worse.

There are two audiences for Kevin Kelly’s essay today. For the aspiring writer/podcaster/YouTuber/artist, the essay is meant as a supportive nudge towards attainable dreams. I can’t get mad at that, even if I find its always-look-on-the-bright-side-of-life schtick pretty exhausting.

But the second audience includes a lot of people asking bigger questions about how we are going to support and fund journalism and art in the digital era. This was also true in 2008, when the essay was originally published. Journalism was in crisis back then. The blogosphere and digital writing didn’t create the journalism crisis. But it wasn't the solution to the journalism crisis either.

For writers especially, Thousand True Fans is a way of coping with the terrible state of journalism and professional writing today. All the journalism institutions are being hollowed out. Maybe the internet can help you make it on your own.

The same appears to be true for musicians and other artists. The old institutions weren’t good. But they’ve been collapsing for decades now, and what’s replacing them isn’t any better. We’re increasingly living in a winner-take-all society. Silicon Valley is one of the main drivers of this trend, and one of the major bulwarks against fixing it. Thousand True Fans encourages us to embrace the individual opportunities and whistles past the broader social trends.

There’s a lesson from the Inflation Reduction Act that I’ve been thinking about for the past week. I think it resonates here as well.

A critical difference from the 2009 climate bill was the willingness to just throw a ton of public funds at the problem. It seems so simple, now that it’s done. If you want public goods, you can do a bunch of elaborate tricks or you can just invest public funds. (And how do you pay for it? You raise taxes on the wealthy.)

For an individual artist, that insight doesn’t mean much. Individual writers and musicians don’t have agency on their own to refund the National Endowment for the Arts. What I want the individual artist to keep in mind when reading Thousand True Fans that it’s still hard out there, and getting harder. You ought to keep in mind that passages like “the most obscure node is just one click away from the most popular node” have aged like stale milk. That was never actually true, and it has become dramatically less the case over time. You’re going to end up slinging t-shirts through Topataco, begging people to support you on Patreon, hoping for some viral hit.

But for the rest of us collectively, we ought to avoid telling ourselves that disintermediation will save artists, or that NFTs will save artists, or that there’s a bright future of journalism in “becoming your own brand.”

If we want good public journalism, it’s going to need public funds. If we want public art to flourish, it’s going to need public funds. The simple solution is the better one.

We can have a tiny rich patron-class whose tastes and whims are the only thing that reliably gets catered to, or we can tax that rich patron-class and use the funds to actually fund the arts again. The tiny rich patron-class loves to quote Thousand True Fans and insist that the technological future is bright if we just embrace innovation (and, y’know, don’t tax or regulate them). We ought to be more skeptical of the story it tells.

Thousand True Fans can be an uplifting philosophy. But it is terrible social policy.

We ought to avoid mythologizing it, so it doesn’t become an excuse for inaction.

I looked at this argument from the fan/stan perspective, l think the one thing missing here is that true fans are presently also evangelists. They don't have to spend much as long as they do the work of worship, which includes proselytizing.

Your Cliff Notes of A Thousand Fans is the current business model for a full-time touring band or solo artist in the trenches. You touch on the results of eliminating all those parasitic middle men, but one more detail is how all-encompassing and exhausting it is. "Connecting" with your fans is a full-time job: constant content generation on Instagram, Twitter, You Tube, and a bunch of other sites, and engaging with comments. All while on the road. Your life is a self-curated open book. And managing the fan club, generating custom content for them is a big part of the engagement process. They do it because you have to work every lever you can grab to keep your head above water. The Thousand Fans fantasy is that you sit at home and self-publish and your fans will "find" you. Yeah, and buy a lottery ticket while you're at it, the odds are about the same.

And don't get me started on the Long Tail. 2 problems (among many)

Who's going to pay for hosting that ever-growing petabytes of content that doesn't generate enough revenue to cover that expense?

How do you find that golden never-been-promoted content that makes you one of those Thousand Fans?

if that niche content is "one click away", the Long Tail requires gatekeepers to host, manage, curate, promote all that content. Meet the new boss... It makes perfect sense that the Web 3.0 scam is built on older scams.