Bullet Points: Everything is Collapsing Edition

Plus, a few ideas about the role of ideas in Silicon Valley

Three observations to share this week, plus a few links:

(1) I’ve been thinking more about that December online debate I had with Jonathan Turley. We were invited to argue about whether Elon Musk’s management of Twitter has gone well or not.

This struck me at the time as an obviously silly question at time, and a more interesting question today.

Because the empirically correct answer, by any reasonable measure, is lolnah. (Or, to be more academically precise and proper about it, lolnahwtfareyoutalkingabout?)

If we compare X now to Twitter before the takeover, things have clearly gotten worse. If we compare X now to Elon’s stated ambitions for X when he acquired Twitter, things have not gone according to plan. Debating Elon Musk’s management of Twitter is a bit like debating the current status of the Washington Wizards — even the devoted fans have to admit that things simply are not going well.

But what makes it a more interesting question today is that it now seems abundantly clear that there exists a class of people who have decided that Elon’s Twitter takeover went perfectly. These are powerful people. People who ought to know better.

And those same people have concluded that the very best thing for the U.S. government is to let Elon Musk run the same playbook at the entire administrative state.

Imagine an alternate universe where Elon’s management strategy had, in fact, worked as intended. Where he came in, fired 80% of the workforce, scrapped the codebase, disconnected the server banks, and… it all worked out as planned. The bots disappeared. User numbers and revenues soared. Twitter 2.0 became the “everything app,” rivaling WeChat.

In that universe, what Elon is doing through DOGE would still be illegal. But I would at least be capable of fathoming the appeal. (“Hey, everyone said it would be a disaster when he tried this at Twitter. And he proved everyone wrong. Who says he can’t do it again?”)

But that’s all just pretend! Elon’s failures at Twitter have been well-documented. And they’re also just so goddamn obvious to anyone who doesn’t live in a hermetically-sealed, ketamine-soaked information environment!

The best argument that Jonathan Turley could make for Elon’s management of Twitter was (paraphrasing) “well I don’t follow these things too closely, but I sure do like it.” That isn’t a good argument. There isn’t any substance to it. But the existence of the argument itself is noteworthy. It tells us that, for the people who now run our government and the people who rely on them for psychic or monetary rewards, lived experience offers no cautionary lessons.

I would like to laugh at these people, but they have their hands in far too many critical systems right now. As Brian Barrett put it, “The US Government Is Not a Startup.”

(2) My friend Katherine Haenschen posed a question on bluesky earlier this week, asking what the Media Theory of Movement Power suggests about avenues for resistance to Trump II.

This deserves some background, since I suspect most of my newsletter readers probably aren’t well-versed in my decade-old contributions to the social movements and contentious politics literatures.

The Media Theory of Movement Power is one of the main theoretical contributions from my 2016 book, Analytic Activism. You can read the relevant excerpt from the book here. The TL;DR version is that we can think of activist strategy as having three layers of analysis. There’s (1) your own resources, and how you deploy them, (2) your opponents and targets vulnerabilities, and how you exploit them (as Saul Alinsky famously wrote, “The action is in the reaction”), and there’s (3) the affordances of the media system, and how you interact with them to amplify your efforts.

This mind you, all comes out of research from the late-Obama years, published prior to the resistance to Trump I. We live in a drastically different world than the one I set out to study and describe. During the early Trump years, it was a pretty useful framework for thinking through Trump’s particular weaknesses and some unique opportunities provided by then-dominant social media platforms.

So the question can basically be condensed to “hey, uh, how about now? Any clever ideas, Dave?”

Here’s what I came up with:

-Historian Nicole Hemmer offered a crucial insight last weekend, writing “A constitutional crisis requires friction to make it legible.” That’s maybe the most important concept for the moment we are currently in. Democratic Party leaders and other institutional figures need to throw sand in the gears and create the sort of dramatic confrontations that media outlets can cover.

(We’re starting to see a few Democrats step up in this regard. We could use a lot more of it.)

This sort of friction is much more accessible to political elites than to social movement organizations, though.

-And/but mainstream outlets are both less influential than they were eight years ago, and their owners have chosen to obey in advance. So their framing and agenda-setting functions will be unreliable at best. Creating a televised spectacle has less of a payoff than it used to, and the higher-ups are going to tamp down on the coverage to avoid pissing off the administration. (This is bad and depressing.)

Elected Democrats are creating friction by showing up and demanding entry to the Department of Eduction, where some of Elon’s Doge goons are currently illegally operating. I don’t know if that will get as much play on CNN or in the Washington Post as it would have eight years ago, though. David Zaslav and Jeff Bezos have made their choices.

-The same goes for social media platforms. We no longer have the centralized social media platforms of a decade ago. The attention backbone of the internet is like a gearbox full of sand.

But it’s probably for the best, because the legacy platforms (Facebook/Instagram and X/Twitter) have thrown in the Trump administration. The tactics that, circa 2017, were rendered more effective because they played well on Facebook Live, etc simply won’t work as well this time. (This is also bad and depressing. Sorry.)

-So the best potential social movement tactics will likely need to combine some mix of surprisingly large-scale and surprisingly deep commitment. (I’m riffing on Charles Tilly’s WUNC, for those who know the social movement literature.)

Those tactics also need to emphasize clear imagery that works with short-form vertical video.

But it’s all further complicated by the specter of potential violent retaliation from government or vigilante actors. Large-scale and deep-commitment are also highly-targetable by an opposition that may not be constrained by the same civil society norms that have historically been present. (This is bad, depressing, and dangerous as hell.)

-Overall, the problem that surfaces for me when trying to analyze the current moment through the lens I developed a decade ago is that Media Theory of Movement Power is premised on bedrock assumptions about (semi)-functional civil society, (semi)-independent press, and (semi)-responsive government. And I’m not certain any of those premises still hold.

…All of which is really just me saying “shit is fucked up and shit” with a more scholarly mien.

(3) What sort of attention should we pay to Curtis Yarvin?

In his newsletter last week, Max Read asked “Is Curtis Yarvin ‘influential.” This was in the aftermath of Yarvin appearing in the New York Times and saying a bunch of provocative-sounding stupid bullshit.

READ: I have trouble being clever and subtle about it: I’m sick of this fucking guy. It’s not just the tedious little sophistries, the smug affect, the endless self-regard--it’s also that I increasingly suspect that his importance to the right is often overstated. It would be too glib even for me to claim that he has no influence at all--Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, and most prominently our current Vice President have all approvingly cited his work--but it seems to me that at this point the reams of exegesis of his work wildly outstrip his actual mark on right-wing politics or culture. (It’s worth comparing his influence on the Trump campaign to that of, e.g., fellow ‘00s bloggers Steve Sailer or Mickey Kaus.) Trump didn’t really run a “Yarvinite” campaign; nor is his administration prusuing a meaningfully “Yarvinite” program. For all his many powerful fans, Yarvin sometimes feels like a hyped baseball prospect I’ve been reading about for years but who still can’t make the opening-day roster--a man with dozens of magazine profiles but no clear wins. (emphasis added)

I think that critique is essentially right. It is worth paying attention to Yarvin and his odious views. But we ought to treat Yarvin as an indicator, rather than as a change agent.

Incidentally, I taught Robert Dahl’s classic 1957 essay “The Concept of Power” in class a couple weeks ago. Dahl offers a simple formulation: “A has power over B to the extent that [they] can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do.”

Dahl’s is a narrow formulation. It leaves out cultural power, or (to use the more technical term) prefigurative power. Dahl’s version of power involves diverting people from their preexisting preferences; Prefigurative power is the power to shape people’s preferences to begin with.

What I have always found useful about Dahl is that it prompts hard, clarifying questions about what tangible differences someone is making.

In the absence of Yarvin’s rambling incoherencies, do we really suspect JD Vance or Peter Thiel or Marc Andreessen act any differently? I suspect the answer is no. So, in the Dahlian sense/in the sense that Max Read articulates, he is not powerful.

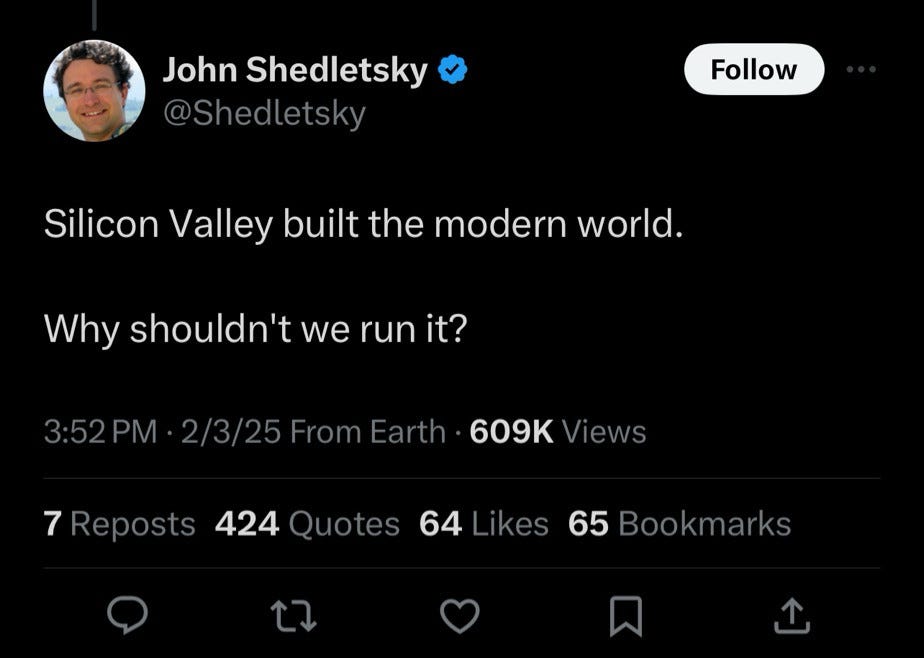

Yarvin has the ear of Vance and Thiel and Andreessen because he says things that flatter their existing preconceptions. (“Tech billionaires are geniuses who ought to rule the world! We need a monarchical CEO to set right all the wrongs caused by foolish bureaucrats who stand in the way of progress and the rightful triumph of your investment portfolio!”)

But Yarvin is an awful thinker and an underwhelming writer. His influence among the Silicon Valley elite comes from telling them what they want to hear, while phrasing it as a bold provocation. He is a court jester, not the power behind the throne. If he said something they didn’t like, they’d just drop the guy.

I think it is worth paying attention to Yarvin as an indicator. His writing is a source of evidence about the utterly odious, ridiculous things that these powerful people manifestly believe. The behavior of the court jester tells us something about the tastes and (moral and intellectual) limits of the royal court.

This is something I’ve wrestled with repeatedly in studying Silicon Valley. The role of ideas in Silicon Valley strikes me as fundamentally transient and contingent. Longtermism and Effective Altruism and Effective Accelerationism and all the rest are little more than fashion trends.

Marc Andreessen and Mark Zuckerberg do not have deeply-held philosophical beliefs that guide their behavior. What they have instead is a set of instincts about how to build companies and products that will bring them money, fame, and the respect of their peers. Philosophy is downstream of power relations. Where they stand depends on where they sit. They genuinely believe today whatever is comfortable for their near-term efforts, and they will genuinely believe something else tomorrow.

The point that I keep returning to is that I wish I didn’t have to care about any of them. If these men were single-digit billionaires, running and investing in well-regulated companies that operate within a robust, competitive marketplace, then I wouldn’t have to care about them.

It is the concentration of wealth and power in so few, manifestly-flawed hands that makes their tastes and failures matter so much to the rest of us.

That concentration is what we most need to unwind. We need to reduce their power, not defeat them in an imagined marketplace of ideas.

A few good reads…

-John Lancaster, “For Every Winner a Loser,” makes plain that the vast majority of financial activity is just pointless gambling, adding nothing of merit to the economy. (h/t Ian Betteridge)

-Becca Lewis in the Guardian, “Headed for technofascism’: the rightwing roots of Silicon Valley.” Becca is one of the very best on this topic. Always read Becca Lewis.

-My copy of John Warner’s new book, More Than Words just arrived yesterday. Cannot wait to read this one.

-WIRED is going so hard these days. There are reporting awards in their future. If you aren’t already subscribed, this is absolutely the time to do so.

This was a really nice read, very sanity inducing (or as much as anything can be at this point in time). I also found your articulation of prefigurative power incredibly useful. Are there any readings that I could explore about it that you would recommend? Understand how it's defined, identified, leveraged?

Is there a worse job than one that requires talking to Jonathan Turley and remembering Mickey Kaus?