[NOTE: this post is sort of an “…and another thing!” riff on my original review of the Walter Isaacson book. I wanted to write something light this week.]

“I am just wired for war, basically.” -Elon Musk, taking a mobile strategy game waaaaay too seriously.

Elon Musk really likes the game Polytopia. He has skipped birthday parties and international business meetings to play the game. He has effused that it is “the best game ever.” He has posited that it is more complicated than chess.

Walter Isaacson treats Polytopia as a window into Musk’s unique, brilliant mind. He devotes nearly as many pages to the game as he does to the Boring Company. (Which is, y’know, one of his actual companies. It has a multi-billion dollar valuation.) He even prints eight “life lessons” that Musk and his hangers-on think you can distill from the game.

It’s… a bit much.

I left Polytopia out of my original review of the book. It seemed like a bit of a strange personality tick. The parallel to SBF’s mobile gaming habit was a little interesting. But I had never heard of the game. I’d never played it. And I already had more than enough material to work with.

A few months later, while visiting some family on the west coast, I noticed my brother-in-law playing Polytopia on his phone. “Y’know, Elon Musk says that’s the greatest game of all time,” I said to him. My brother-in-law gave me a quizzical look. He’s a pretty well-adjusted fellow, neither addicted to Musk nor Polytopia. He just thought the game was reasonably fun.

So I tried it out.

Here’s what I can tell you about the game: It’s… fine. It’s a nice little time-killer. Calling it the “best game ever” is a bit like calling Ant-Man and the Wasp the greatest film in the history of cinema. It tells us far more about the psyche of the person making the claim than it does about the game itself.

Polytopia is developed by Midjiwan, an indie game company. It is a cheap game. You can play the whole thing for free, or you can unlock additional tribes to play for $1-2 apiece. The most you can spend on the game is $30.

(This, by the way, strikes me as capitalism at its best. Midjiwan built a fun game. People play and enjoy it. Those who really enjoy it decide to spend a perfectly reasonable amount of money to enjoy it some more. Good for them. They seem like good folks. I wish them the best.)

The game isn’t trying to be Fortnite or Roblox. It isn’t attempting to redefine gaming. There is nothing particularly unique or innovative about it. If you enjoy turn-based strategy games, you’ll probably like it. But you’ll also figure the whole thing out pretty quickly. I was able to beat the game on its hardest settings with every character class after a couple dozen playthroughs.

I cannot fathom how anyone would think it is more complex than chess.

The strategy in Polytopia is straightforward. The game generates a new map every time, which keeps you paying attention, but generally you’re trying to (1) expand your territory, (2) generate more stars (the resource that you spend each turn), (3) unlock stronger units, and (4) find and demolish your opponents.

So you will always spend your first few turns exploring your surroundings and upgrading your first town. Then you encounter some map-based challenges, and build toward overcoming them.

The “tech tree” is straightforward and, after a few playthroughs, it becomes pretty obvious which slots to unlock in which order. (You’ll need archers to defeat early-game opponents. You’ll need bombers to overwhelm late-game opponents. If you have a lot of bombers, you are unbeatable.)

The game constantly engages your executive functions. You gauge conditions and make resource allocation decisions, proceeding across the map in a straightforward manner. It only takes about 45 minutes to play a full game. It’s a nice way to occupy yourself during a short plane flight.

But it is not a particularly addictive game. Starcraft is a harder and more addictive strategy game than this. Slay the Spire is a harder and more addictive mobile strategy game. Tears of the Kingdom is not a strategy game, but my god you will lose a month of your life to Tears of the Kingdom.

I’d say the game is about as addictive as sudoku.

Looking back on Isaacson’s book, this casts the Musk anecdotes in a different light. Isaacson tells a story in the book about Musk flying to Mexico for his sister-in-law’s birthday party. Grimes is DJing. His family and close friends are all there. But Musk doesn’t leave his room. He plays Polytopia all night instead.

Isaacson treats this as evidence of Musk as a deft, dynamic strategic thinker who has trouble taking pleasure in normal-people things. Isaacson never clocks that this means he must have played a half-dozen games of Polytopia. And he also never realizes that the game just isn’t that hard.

If someone flew to Mexico for a fancy party and then skipped the whole thing to play sudoku in their hotel room, you probably wouldn’t think “such an ineffable genius.” A more reasonable reaction would be “oh shit that guy desperately needs to talk to a therapist.”

There’s an old saying about poker: “it takes five minutes to learn and a lifetime to master.” Polytopia takes five minutes to learn and maybe twenty hours to master.

And look, I don’t mean that as a critique of the game. I can see why my brother-in-law likes it. I like it as well. I am entirely in favor of indie game studios producing fun little mobile games that I can enjoy on a plane flight.

But it raises a question that Walter Isaacson never asks. Because Isaacson, as far as I can tell, found Musk’s little gaming addiction to be a delightful detail without ever trying out the game himself: why this game? What does it say about Elon Musk that he finds this particular game so appealing?

I think the answer is simple: Elon Musk only plays games that he can dominate without working too hard at learning the rules.

Polytopia is not complicated. There aren’t a ton of divergent strategies. The game rewards aggression and domination. You build up resources, unlock the tech tree, and kill your opponents. The fog of war and randomly generated maps make for a new challenge every time, but it’s also the same challenge every time. And you either recognize early that the random map put you in an unwinnable position or you get the satisfaction of an inevitable march to victory.

There are no surprises or hidden reversals late in the game. Once you control half the map and have a resource advantage, taking over the other half of the map is a light downhill jog.

By comparison, chess is a game where one can spend much of the game believing they are in the lead, only to find that they had been trapped all along. Chess is a game of extraordinary sophistication, requiring years of study. There is a reason why “beat a chess grandmaster” was, for so long, an artificial intelligence benchmark.

Poker, meanwhile, is a game of incomplete information. One of the most frustrating parts of the game is that you can outplay your opponent and still lose. In fact, most of your biggest losses will happen when you were in a position of strength — You get the money in with the stronger hand, but catch a bad river card. You flop middle set against your opponent’s top set. One of the major skills for high-level poker play is emotional regulation. You have to learn to manage the emotional rush of outplaying your opponent and losing anyway.

(Musk, as I noted previously, is a terrible poker player.)

The appeal of Polytopia is that it isn’t hard to tell whether you are winning or losing. And you will be right. You get the satisfaction of beating the computer, or of beating your friends in a multiplayer online game. You won’t win every time, but you also will never be surprised.

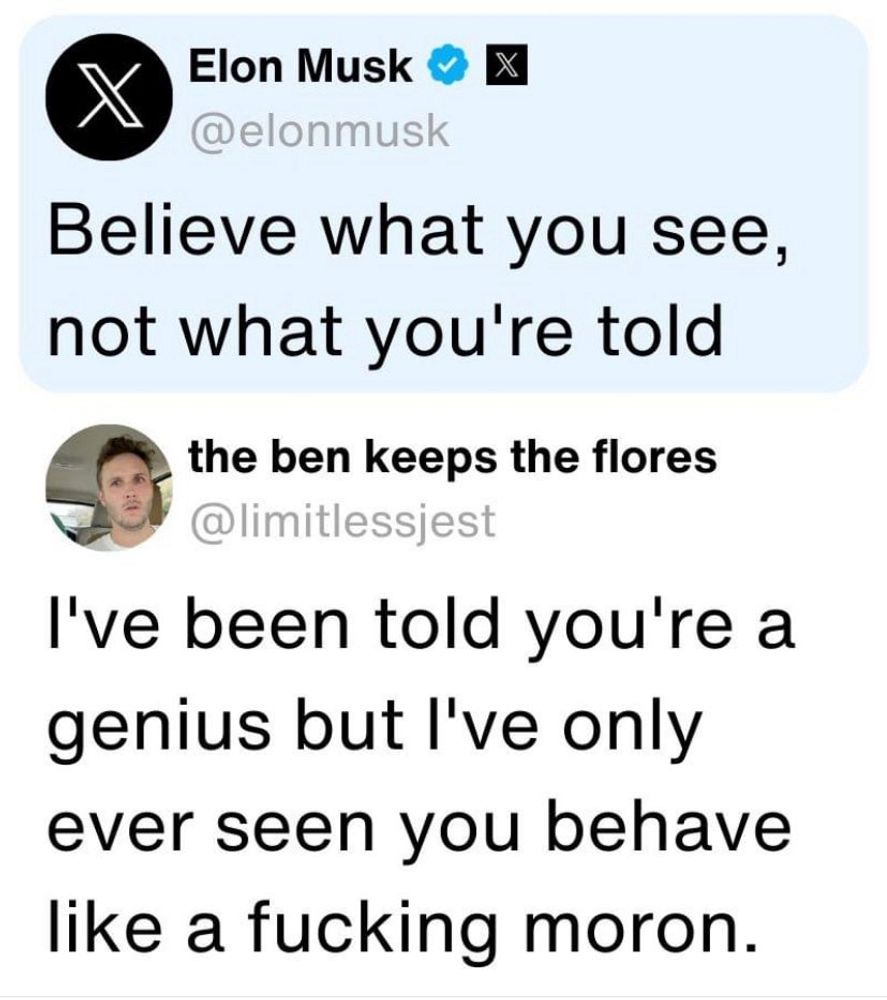

The central contradiction of present-day Elon Musk (now that the real-world-Iron-Man myth machine has broken down) is that he has attained such phenomenal wealth while behaving like such an utter fool. We are constantly encouraged to suspend disbelief—surely there must be wheels within wheels, layers upon layers that would cast his impulsive actions in a different light. The man just fired the entire team behind Tesla’s Supercharger network, which was supposed to be the company’s firewall against its competitors. Is this exactly what it looks like, or is there some brilliant gamesmanship that we normal folks cannot see?

Isaacson assumes the latter. That’s the premise of the whole endeavor. And so he latches on to Musk’s Polytopia habit as evidence of something deep, special, and unique.

But Isaacson didn’t take the time to actually play Polytopia. Hell, he seemingly didn’t even read any reviews of the game. And, having played Polytopia, a different story emerges:

There are no hidden layers to Elon Musk’s thinking. He likes the gratification of impulsively pushing a button and seeing the numbers go up. He likes games that are straightforward and easy to beat. He’d rather reset every 45 minutes than execute meticulous plans that extend far into an uncertain future. He does not think ten moves ahead. He just responds with maximal aggression to the latest change of conditions. (The stock is down again. Announce robotaxis!) When this works, he gets the satisfaction of dominance. When it doesn’t, he can always just reset and try again.

Elon Musk’s suit of armor is that he is extremely rich. He made a couple of high-risk, high-reward bets that paid off. He doesn’t have some grand, overarching insight into the nature of business, science and technology, or humanity. He is exactly who he appears to be.

He’s the guy who thinks Polytopia is more sophisticated than chess. The guy who loses a ton of money going all-in on a dozen poker hands, just for the satisfaction of finally winning one. He runs each of his companies the same way. He gets away with a lot, simply because he has amassed so much money and marketshare that the normal rules don’t apply to him.

That’s the real lesson from Musk’s obsession with Polytopia. The man doesn’t have hidden depth. He’s actually pretty… basic.

I'd say Musk is a man with "hidden shallows", but they're not exactly hidden anymore, are they?

I quite enjoy polytopia as a simpler, less addictive Civilization. It’s just fun and you don’t need to think too hard. So, I agree with almost everything you said.

Multiplayer polytopia is a different beast. It brings the complexity and strategy up to the level of Backgammon. If you enjoy single player and find it too easy, try multiplayer.

To be absolutely clear, it’s still a simple, but fun game.