The myth of technological inevitability

Lessons from the 1990s human cloning debate

“Whatever can be done, will be done. If not by incumbents, it will be done by emerging players. If not in a regulated industry, it will be done in a new industry born without regulation. Technological change and its effects are inevitable. Stopping them is not an option.” -Andy Grove, 1998

“Cloning is inevitable. If I don’t do it, someone else will. There’s no way you can stop science.” - Richard Seed, 1998.

Of all the imagined futures buried in the pages of the WIRED magazine back catalog, I think one of the most instructive is the argument for the “inevitability” of human cloning.

In 1996, researchers at the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute cloned Dolly the sheep. Human cloning, it appeared, could not be too far behind. President Clinton declared a moratorium on federal funding for human cloning research. Governments across the world took similar steps. It was the rare moment when, instead of adopting a laissez-faire/“let markets decide” approach, elected officials asserted themselves on a major social issue.

In the pages of WIRED, this was sacrilege. You can’t stop scientific and technological progress! If the U.S. government wasn’t going to fund this research, that just meant some (privately funded) “rogue lab” would do it on their own. Or maybe (*gasp*) China would seize the initiative.*

*(In the eyes of libertarian tech-optimists, the United States’s historic dominance in science and technology is entirely due to its willingness to let innovators innovate, keeping regulators out of their way. That the U.S. government provided ample public funding for basic research, and that the Defense Department was frequently the sole customer for their products were inconvenient facts, signifying nothing.)

And so, between 1997 and 2002, WIRED routinely articulated the case for why human cloning was the future, and it would be good, and everyone ought to just get used to it.

In the June 1997 issue of the magazine, Microsoft CTO Nathan Myhrvold contributed an essay titled “in vitro veritas,” where he attempts to brush off the deep ethical debates surrounding human cloning:

"Fear of clones is just another form of racism. We all agree it is wrong to discriminate against people based on a set of genetic characteristics known as "race." Calls for a ban on cloning amount to discrimination against people based on another genetic trait - the fact that somebody already has an identical DNA sequence. The most extreme form of discrimination is genocide - seeking to eliminate that which is different. In this case, the genocide is preemptive - clones are so scary that we must eliminate them before they exist with a ban on their creation.

The most upsetting possibility in human cloning isn't superwarriors or dictators. It's that rich people with big egos will clone themselves. The common practice of giving a boy the same name as his father or choosing a family name for a child of either sex reflects our hunger for vicarious immortality. Clones may resonate with this instinct and cause some people to reproduce this way. So what? Rich and egotistic folks do all sorts of annoying things, and the law is hardly the means with which to try to stop them.

(I’ve bolded that last bit because, given Myhrvold’s longtime friendship with Jeffrey Epstein, I think it speaks volumes.)

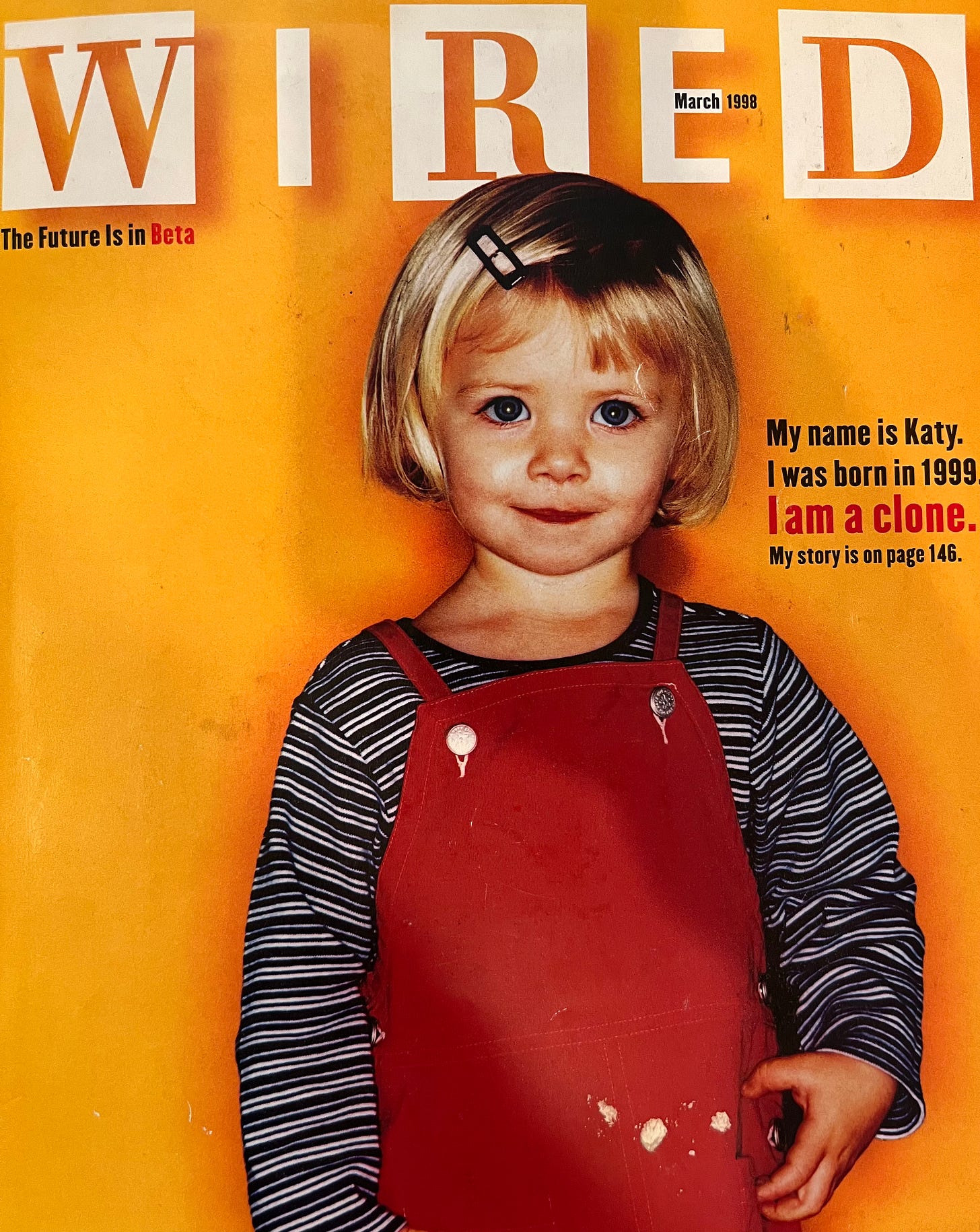

The March 1998 issue was even more jarring. The cover depicted a blue-eyed, blond-haired child. “My name is Katy. I was born in 1999. I am a clone. My story is on page 146.” The article, Richard Kadrey’s “Carbon Copy,” is speculative fiction, but the magazine takes pains to make it seem real.

The story hinges on an imaginary team of University of Pennsylvania biologists who, circa 1998, disregarded Clinton’s funding moratorium and cloned a human child. “If we win the Nobel Prize, I wonder if they’ll let me keep mine in my cell,” one of the pretend-scientists remarks. The biologists keep quiet for years, in the hopes of giving the child a chance at a normal life. Kadrey writes from the near-future, when news of the kid’s existence finally becomes public.

That’s the thrust of the piece: all the ethical handwringing over human cloning is rendered moot, because scientists are just gonna science. Once we find ourselves live amongst clones, everyone will just have to get over their hangups and adapt.

It’s a nice piece of writing. Apparently it was turned into a Lifetime movie. But some of the details ring false. The behavior of his imaginary scientists is, upon closer inspection, wildly unrealistic. For one thing, they wouldn’t just be defying President Clinton’s declared moratorium. They would also be lying to the Institutional Review Board. They’d be falsifying internal documents like annual reviews. This is mundane stuff, but it’s mundane stuff that University lawyers would absolutely have you fired over.

And this wouldn’t just be one rogue scientist — it would be an entire research team. The professional penalties for that kind of behavior are significant. Every member of the team would be fired for cause (tenured or not). The postdocs would be unemployable. It may still all sound tempting in the fictional account where success is guaranteed. But that is not the reality of lab life. It took 277 tries to clone Dolly the sheep. Are we to believe this whole imaginary research team is going to gamble their careers and commit career-ending fraud just for the thrill of the scientific challenge?

In other words, it’s only a compelling science story for non-scientists. (It reminds me of the Netflix show, “The Chair.” Plenty of people enjoyed that show! Zero of them were academics. Academics every agonizing moment of that show muttering “that's not how it works…. That’s not how any of this works!”)

The same issue includes an essay by G. Richard Seed, the physicist/failed biotech entrepreneur who ignited the debate over human cloning by publicly declaring that he would clone a human before any regulatory prohibitions could be passed. Seed’s essay focuses on how cloning is actually going to bring us closer to God, in a way that all proper Christians ought to celebrate. The essay concludes with the pronouncement, “Cloning is inevitable. If I don’t do it, someone else will. There’s no way you can stop science.”

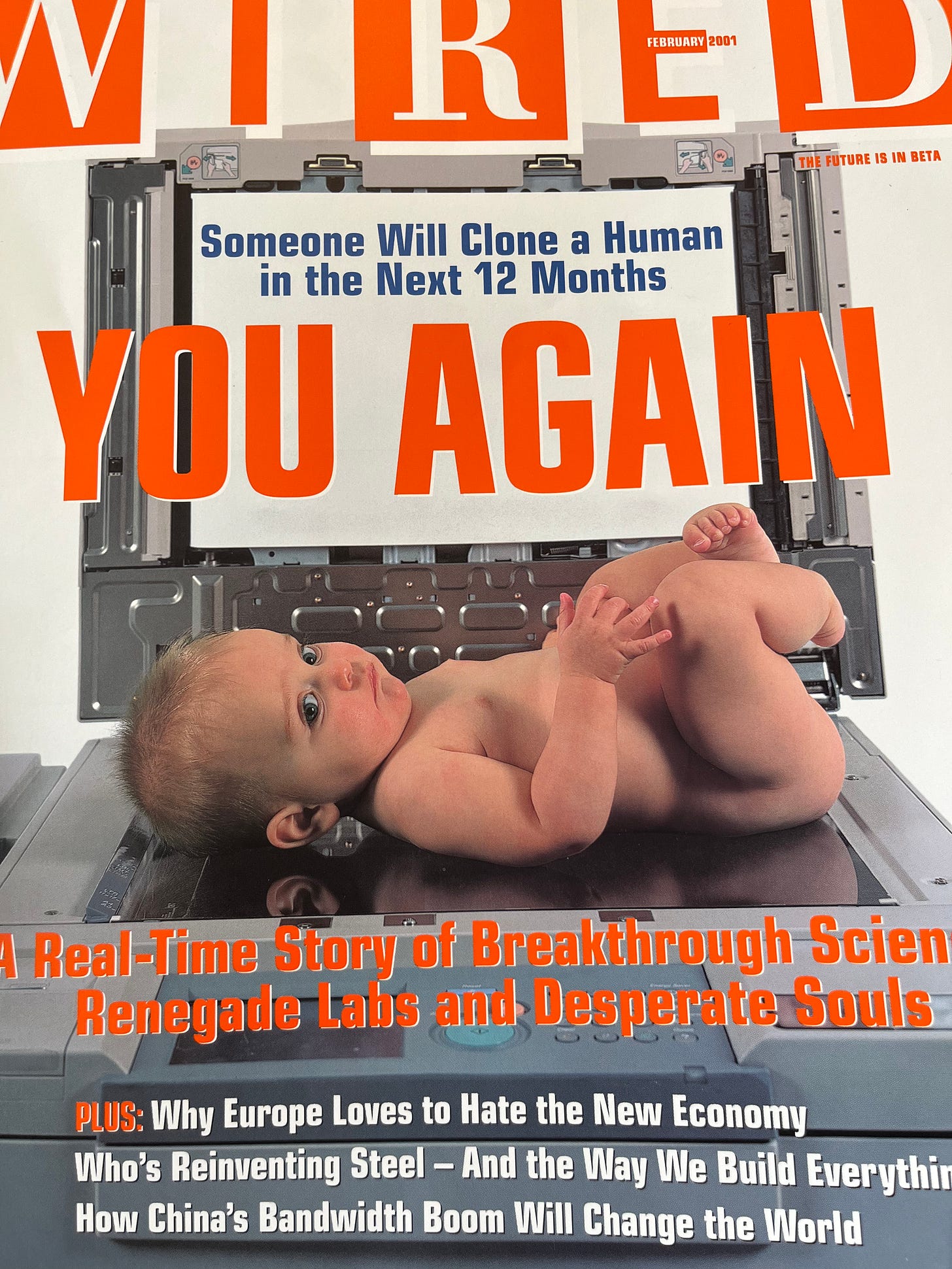

In February 2001, human cloning was back on the cover. “You(2): Someone will clone a human in the next 12 months,” by Brian Alexander follows a motley crew of rogue scientists, all of whom insist that they are just on the verge of cloning a human. (Including, oddly, the Raelian UFO cult?)

The people Alexander follows around insist that the science of human cloning has all-but-arrived. The ingredients of this tale have the feel of a speculative fiction story — a maverick scientist who thinks he has worked out the procedure, a rich, grieving, wealthy father who is willing to ignore all ethical quandaries to get his son back, an underground of discussion-board fanatics surfing the edge of the possible. It’s all shrouded in secrecy now, but Alexander hints that’s an unstable status quo:

“It will be a big bang all around the world when it happens. (…) When we finally hear that bang, it’s liable to come from somebody like the Creator, a self-starter with just enough skill to make human cloning work. The fact that society generally frowns on the idea doesn’t mean it won’t come to pass – it just means it will probably happen secretly, at least the first time.”

What stands out is how facially reasonable this all seems. There is demand for human cloning — particularly from rich iconoclasts. Alexander writes “Where there is a demand, there will probably be a supply. You can already see it: A cloning infrastructure is slowly emerging to satisfy a market that doesn’t quite exist yet.”

The implicit model here is of science as heroic achievement. You can’t stop scientific progress, because rogue geniuses will bend the rules and push us into the future. If society “frowns” on those breakthroughs, then society will just have to adapt.

Elsewhere in the article, Alexander writes:

“All of these activities point to an unmistakable conclusion: Human cloning has become inevitable. ‘It will be done by someone, somewhere,’ Columbia’s Sauer asserts. And when it’s done, say experts, we’ll be in for a major shock. Not because human cloning will be as terrible and disruptive as widely assumed. But because we will realize that most of our ideas about it were all wrong, that the cloning fostered by our imaginations and nightmares doesn’t really exist. We’ll also see that the ethical hand-wringing over the issue is anachronistic compared with other biotech dilemmas waiting just around the bend.”

He also interview Michael Bishop, president of Infigen. Bishop insisted that the first human had likely already been cloned. “It is being done. I have no doubt. It would be stupid and naive to think it’s not. (…) It is too easy. Too bloody easy.”

Bishop’s Infigen had a claim to the patent on the procedure used to activate egg division in animal cloning. It appears that the company’s biggest revenue streams was patent infringement lawsuits. It lost a patent dispute in 2003 and promptly shut down. …Nothing about these scientific advances, turned out to be “bloody easy” after all.

The interesting thing, reading these articles with a couple decades of hindsight is how stale this self-assured tone now seems. None of this came to pass. Human cloning is still the realm of science fiction and conspiracy theories. Alexander’s conclusions were aspirational. There has been no “big bang all around the world.” That rogue scientist didn’t have it all worked out. That rich, grieving father did not get his son back. And the reason, simply put, is that the heroic scientist model is bullshit! Absolute bunk. It is the stuff of speculative science fiction, with no bearing in reality.

Scientific breakthroughs don’t come about because a lone, dashing genius decides to break all the rules. Science is much harder than that! And it is so much more boring than that, too! You need labs. And equipment. You need a research community that stress-tests your assumptions and checks your errors and evaluates alternate rival explanations.

The secret of foundational scientific research that the VCs and the entrepreneurs constantly whistle past is that it is extremely expensive and the private sector barely chips in. This is one of the major points that Mariana Mazzucato makes in her (excellent) book, The Entrepreneurial State. Basic research isn’t just risky; it’s uncertain. VCs have an appetite for risk. They’ll fund 100 companies, expecting three to succeed. But they have no appetite for uncertainty. They aren’t going to sink money into a hadron collider on the off chance that it will produce some scientific breakthroughs that eventually translate into marketable products. Mazzucato includes a fantastic quote from Nobel Prize winner Paul Berg, who was attending a dinner in 1984 with the proud venture capitalists who had started the biotech firm Genentech:

“Where were you guys [venture capitalists] in the ‘50s and ‘60s when all the funding had to be done in the basic science? Most of the discoveries that have fueled [the industry] were created back then.”

If you want big scientific breakthroughs, you’re going to need tons of funding and a lot of time. The private sector isn’t going to get involved until scientific uncertainty has been replaced by financial risk. If the funding isn’t there, and/or there are regulatory roadblocks (for good reasons OR bad reasons), there just aren’t going to be many breakthroughs.

(A positive recent example is the “Green Vortex” in the renewable energy sector. It turns out that once the public sector decided to prioritize renewables, the pace of technological innovation blew away even the rosiest forecasts. …If only we had tried that ten years earlier.)

Here we are, in 2024. The course of biomedical research has moved in the direction of CRISPR and gene therapies. The human cloning future proved to be neither inevitable or immutable. The path of scientific progress veered in different directions.

And, honestly… good! Does anyone regret that we haven’t empowered rich egomaniacs to create clones whose organs they can then harvest? When you tally up the state of the world today, with all its problems and opportunities, do you find yourself thinking “aw damn. It sure would help if we had clones”?

(Nathan Myhrvold might regret it, I suppose. Who knows what he regrets?)

The broader lesson is that inevitability was never more than a framing device. The arguments for developing human cloning on the merits — not stem cell research, but full-replica human beings — were never particularly compelling. Inevitability serves as a rhetorical dodge, an attempt to change the temporal register of the argument from “if” to “when.”

Once we discard the heroic scientist model and the myth of tech inevitability, the course of technological and scientific advancement looks less like a railroad track and more like foliage. It has roots and branches that extend in the direction of the resources that feed it. We cannot precisely dictate or schedule that growth, but we do have substantial capacities to influence it.

I alluded to this point a few months ago, in my critique of Marc Andreessen’s “techno-optimist manifesto”:

Andreessen (…) describes “technology” as if it was an innate force that can either be accelerated or decelerated. It’s as if we have a single knob that can be adjusted up or down.

Andreessen styles himself an “accelerationist.” He labels his opponents as “decelerationists.” Decelerationists are the enemies of progress. He writes “We believe any deceleration of AI will cost lives. Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.”

This is just a comically oversimplified view of technology. It's narrow and it's self-serving. Technology isn't a dial.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can roughly approximate the pace of technological development. (…) But we can also affect the direction of technological development. Technological “progress” does not occur along a single, fixed path. Its course is heavily influenced by people, existing institutions, and incentives.

(Close readers who have been following my writing for a while may be sensing a theme here. And yes indeed, this is all draft material for the book.)

The lesson from the human cloning debate is that there is a substantial role for the public sector in determining the course of scientific progress. And this is the lesson that tech accelerationists appear most eager to avoid. Because if we have functional levers for influencing both the pace and direction of science and technology, then we might choose policies and public funding commitments that do not reward their investment portfolios. We might stop treating the tech barons like conquering heroes.

Consider what this implies for today’s “inevitable” digital future: Generative AI. It has become commonplace for tech evangelists to insist that, good or bad, these technologies have already arrived and we will just have to get used to them. Folks like Sam Altman repeatedly promise that artificial general intelligence (AGI) is a near certainty — that we should root for OpenAI because if his company doesn’t build it, someone else will.

Perhaps we shouldn’t accept their insistence that AGI is inevitable. That is an aspirational claim, meant to shift the temporal register. Maybe we should demand that he explain and account for why this future he is trying to build is desirable.

The inevitability myth is an essential part of the political project of Silicon Valley.

We can see from our own lived history that it is not grounded in reality. We ought to stop pretending otherwise.

So as you know, basic research is often called “Deep Tech” in VC circles. And, yes, it gets a fraction of the investment of software or marketplace or e-bikes. The life of a fund is typically 10 years - so if your potential business can’t get a “liquidity event” in that time, it’s a non-starter.

In Australia, the most prominent Deep Tech VC firm (Main Sequence) was founded by a govt agency (CSIRO) - Mazzucato‘s revenge. A local, well-respected university is starting a pre-seed fund to support their scientist’s inventions because the commercial VCs won’t.

Well argued and laid out. Building on your “markets / demand for cloning point” I’d argue that the demand shook out more on gene modification rather than full on cloning. It seems there is a market for and active work around gender selection and other modification to reduce the chance of genetic disease or attempts to select for characteristics. In certain parts of society there is considerable demand to “design” your children.