Talking "Bretbug" in the Classroom

Lessons from that one time I ended up living my strategic political communication syllabus

I taught the Bretbug case in my strategic political communication class this week. It’s weird teaching a case study where you’re the main protagonist. But it would be weirder not to teach it, I think.

The Bretbug episode hits right at the center of a few themes from my class. It’s a classic example of “conflict expansion.” It illustrates the way that influencing the length of a contentious episode can be as consequential as influencing the content of a contentious episode. And it also highlights just how little is ultimately at stake when battles over public attention aren’t translated into structural change.

Since I imagine the venn diagram of my Substack readers, my Twitter followers, and people-who-were-entertained-by-the-Bretbug-thing is basically a bullseye, I think it’s worth sharing a summary of my lecture notes here. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, or could use a refresher, these two articles do a nice job of covering it.

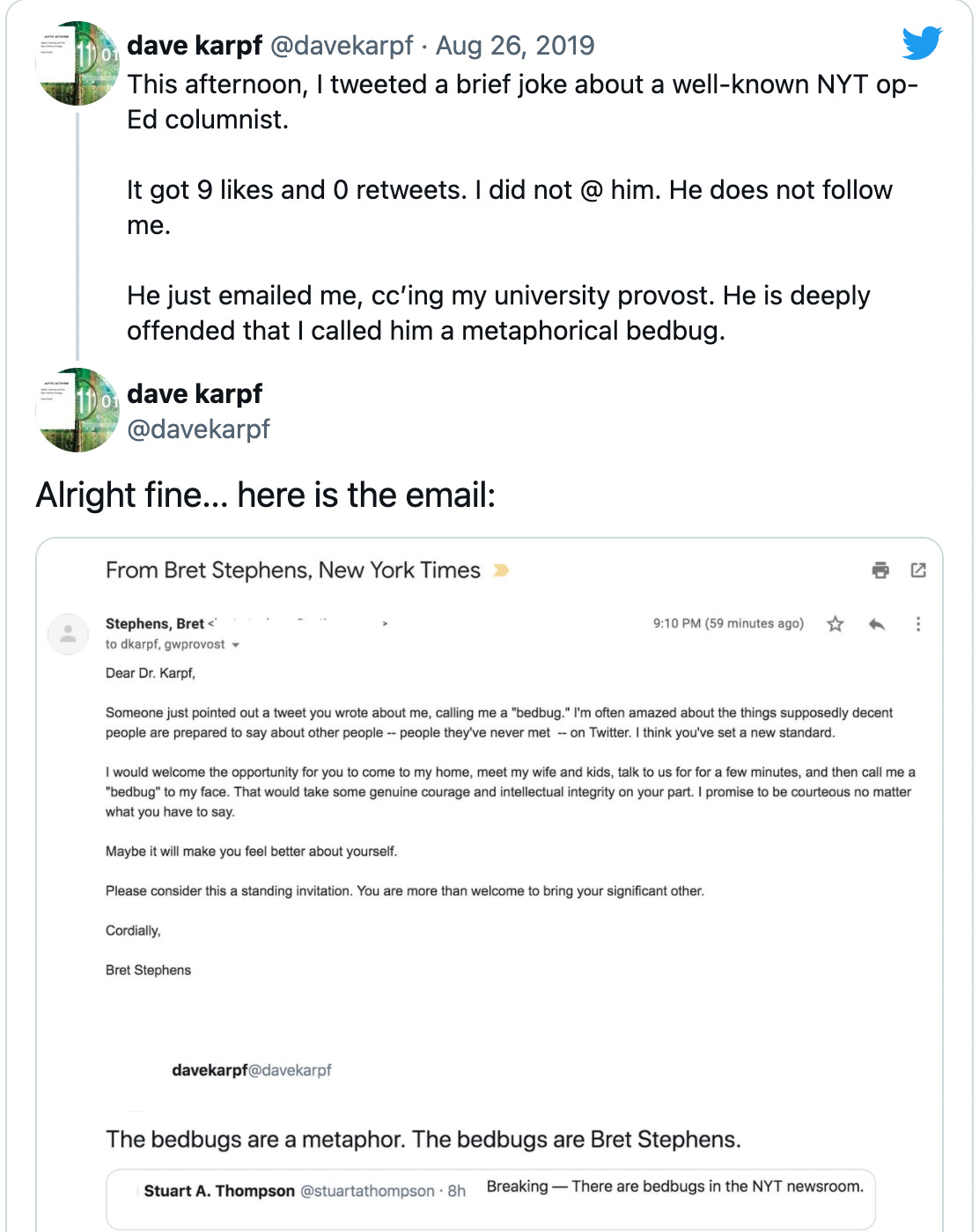

[TL;DR version: I tweeted a milquetoast joke about Stephens. He found it, lost his mind, and emailed me and my employer to say that I had set a new low for civil discourse on the web. I posted the exchange to Twitter. It went extremely viral. He quit Twitter. He then wrote an entire New York Times column about how liberals being mean to centrist pundits on Twitter are today’s equivalent to nazi propagandists. It was quite a week.]

Now, on to the broader lessons. Let’s talk Schattschneider, shall we? :)

(1) Politics is (still) about conflict expansion. Know your Schattschneider.

I teach this case alongside E.E. Schattschneider’s classic book (1960), The Semi-Sovereign People. Schattschneider introduced the study of conflict expansion to the field of political science. Conflict expansion predates framing theory, and I would argue that an awful lot of framing theory is better understood in Schattschneiderian terms.

In the opening pages of the book, he writes:

“the outcome of every conflict is determined by the extent to which the audience becomes involved in it.”

Later, he elaborates further:

“Political conflict is not like an intercollegiate debate in which the opponents agree in advance on the definition of the issues. As a matter of fact, the definition of the alternatives is the supreme instrument of power… He who determines what politics is about runs the country” (66).

Put more plainly, the trick to turn a losing situation into a winning situation is to change who is involved in the fight. The side that wins a contentious episode isn’t the one making the best argument; it’s the one determining who is involved and what they will be fighting about.

When Stephens initially emails me, cc’ing the university Provost (my boss’s boss’s boss, essentially), he is making a strategic decision about the boundaries of the interaction that will follow: I have offended him. He is an important person. My employer ought to know what I’ve been up to. We’re going to have a conversation about my behavior.

If I accept the structure of that interaction (who participates and in what setting), then all I can really hope to achieve is damage control. The best-case scenario is that the Provost will stand up for my academic freedom to make silly internet jokes, while still being annoyed that this has been put on his to-do list for the day. (There is simply no universe where a University Provost thinks to themself, “you know what I definitely have time for? Managing the fallout from a snippy New York Times columnist who one of my professors has offended for no particular reason. I am so glad to make this a priority today.”)

If we handle this by the rules that he has established, the smart choice is for me to offer a bland apology, explaining that the joke was not intended for him and I did not intend offense. Then I can hope the whole thing goes away and doesn’t escalate into a bigger, dumber controversy. It’s a no-win situation; time to limit my losses.

But Schattschneider tells us that political conflict is not an intercollegiate debate where the participants and rules have been settled in advance. And I’ve been studying Schattschneider for almost twenty years.

So, instead of replying to him, I expanded the scope of the conflict. I had a strong hunch his unprompted email to me and the Provost would be a lot more interesting, outrageous, and entertaining than my initial twitter joke (which, let’s face it, had completely bombed). Stephens wanted an audience of one, for a conflict of my tweet. I decided it would be preferable to have an audience of everyone, for a conflict about his overreaching behavior.

Notice how this changes the power dynamics. No longer is this an email exchange between a NYTimes columnist, some professor with questionable taste in social media, and a Provost who, by nature of the job, must not have time for this nonsense. Now it is a story about the NYTimes columnist who spends his days writing columns with titles like “Free Speech and the Necessity of Discomfort,” and his nights scouring the internet for any speech that causes him discomfort so he can demand to speak to the manager. (Discomfort for thee, but not for me.)

Once the conflict has expanded, Stephens has effectively lost. I doubt it occurred to him that I might screencap and share his message. The overwrought tone of his message was an asset in an interaction limited to me and the Provost (“oh wow, this guy is really upset. Did I cross a line?”) and a liability when shared with the rest of the digital world (“He asked you to call him a bedbug in front of his wife and kids?!?”)

The main risk with this tactic is that, if my second tweet had failed to go viral, then I likely find myself in even more trouble. It isn’t particularly classy to share someone’s private email message on social media. If it hadn’t gotten traction, if my attempt at conflict expansion failed, then I look like a real asshole — making mean jokes and then getting even meaner when someone challenges me on it. And I mention the potential risk because conflict expansion is almost never this easy. In most political conflicts, both sides are actively attempting to expand or contract the size of the audience.

…Then again, Bret Stephens is clearly the type of guy that thinks political conflicts are decided by whoever can summon the more poignant Churchill quote. You couldn’t ask for an easier opponent.

I think the Bretbug case is pure Schattschneider, and a nice illustration of how some fundamental concepts from 60+ years ago still resonate today. Stephens set up an interaction where I could, at best, contain the damage. I executed a pivot that expanded the conflict. Once the pivot succeeded, the only way Stephens could stop losing was to stop playing.

Which brings me to the second lesson: clock management.

(2) Influencing the length of a political conflict is often just as important as influencing the substance of a political conflict.

In my analysis, Bret Stephens made three blatant strategic mistakes.

First, he shouldn’t have emailed me to begin with. (Don’t do that, man. Don’t name-search yourself on social media on a random Monday night. Don’t track down the people who wrote mean tweets about you. Don’t email them. Definitely don’t cc their employer. It’s unclassy. It’s also reputationally risky. What, exactly, do you hope to gain from those interactions anyway? What does a “win” look like?)

But everyone has a bad moment. Who hasn’t sent an email that they should have saved to the drafts folder and then forgotten? From a strategic perspective, the other two mistakes are much worse, because they are foreseeable and preventable.

The second mistake was on Tuesday morning, when Stephens went on MSNBC and was asked about the exchange. Stephens, at this point, had suffered through a rotten night of getting roasted on the Internet. His goal should have been to give no new fuel to the controversy.

Here’s what he should have said: “y’know, that wasn’t my finest moment. I probably shouldn’t have emailed that online commenter. I don’t think he should have published my private email. Neither of us were our at our finest. Social media can bring out the worst in people, and I’m glad to have finally deleted my account. Engaging to begin with was a mistake.”

That’s a bland and boring statement, admitting some fault and regrets without getting into the particulars. It’s a wet blanket of a statement. And strategically, a wet blanket is exactly what he needed. It’s a copout, but it also ends the story. People will get bored of dunking on him. They’ll move on to the next thing. Hell, this is all happening during the Trump era. The next collective outrage will arrive before lunch.

Instead, Stephens tries to explain and defend himself. He tells the news anchor that in cc’ing the Provost, “I had no intention whatsoever to get [Karpf] in any kind of professional trouble but it is the case that… managers should be aware of how their [employees] interact with the rest of the world.” The anchor later inquires, “Um… Is that the worst thing that you have ever been called on social media?” He responds, “there is a bad history of being analogized to insects that goes back to a lot of totalitarian regimes.”

Bad move.

OF COURSE after that segment, I spent the whole day fielding calls from reporters. Every reporter wanted to know what I thought of his statement. Did I buy his claim that he wasn’t trying to get me in professional trouble, he just wanted my manager to be aware of the terrible things I was saying? (Response: no. Those two clauses directly contradict each other. Somebody get this man an editor.) What did I think of his suggestion that I was behaving like a totalitarian regime? (Response: that’s ridiculous. Also, it’s a reminder that this is about power asymmetry. He’s a New York Times columnist using his position to punish people who say mean things about him. I’m just some professor, who thankfully has tenure so I don’t have to put up with this nonsense. But if he’s doing this to me, he’s definitely doing it to people whose employment status is more tenuous. A tweet with 9 likes and 0 retweets is in no way similar to totalitarian government propaganda. Duh.) And how do I respond to claims that I had used an anti-semitic slur? (Response: Uh, I’m jewish. That’s really not a thing.)

Imagine if Stephens instead had offered the wet blanket response. I would have gotten fewer calls from reporters. Those who did call would have asked, “Stephens thinks he shouldn’t have emailed you or your employer, but doesn’t like that you published his email. What do you think?” (Response: yeah, that sure turned into a bad night for him. Pretty funny, right? Hopefully he learns not to send emails like that in the future.) The story dies out if you don’t keep fueling it. Stephens treated his MSNBC appearance as an opportunity to score points in an asymmetric debate (he has a tv appearance. I have a Twitter account).

It’s just sloppy. Stephens earned himself an extra day or so of Internet-roasting because he couldn’t admit he had made a mistake.

But that pales in comparison to the Friday night column. By Friday, the controversy was well and truly over. Reporters had stopped calling. The tweets had stopped being retweeted. The Internet had found other things to find collectively outrageous and/or hilarious. It was done. And all he had to do was write his weekly opinion column about something else, anything else.

Instead, he devoted his whole column to a bizarre comparison between Nazi propagandists’ use of radio in the 1930s and liberal intellectuals use of Twitter today to speak pejoratively about “The unpopular political figures of our day… the moderate conservative, the skeptical liberal, the centrist wobbler.” For literally anyone who had spent time online that week, the subtext was plain: the jewish professor who tweeted an insulting joke about me is just like a Joseph Goebbels.

Here was my immediate reaction:

Set aside the substantive problems with Stephens’s column. It’s garbage. It’s unserious and unethical and mean and petty. What a small man Bret Stephens is.

From a strategic perspective, it’s also incredibly counterproductive. I noted at the time that Stephens had managed an internet-first, pulling off a Streisand Effect/Godwin’s Law back-handspring. Of course the entire Internet pummeled him again after this column. Of course every news outlet published a follow-up story. Of course it gave new life to a controversy that otherwise would have ended.

What Stephens couldn’t grasp was that the only way to stop losing was to stop playing. He was still trying to score debate points, and using all of his (considerable) media resources to do so.

But political conflicts are not intercollegiate debates. And, particularly with today’s attention economy, the fight is as much over time-share as it is over substance.

(3) So… what did you win, exactly?

The last point that I want to emphasize is just how small this all ultimately was.

By any reckoning, Bret Stephens lost this fight and I won. But what did he lose? What did I win?

Before #Bretbug, Bret Stephens was one of the New York Times’s house conservative opinion columnists. His columns were pretty lazy, often hitting the same two or three themes (concern-trolling Democrats, complaining about kids-these-days, fretting about cancel culture, etc). He was openly scorned on Twitter. He had a Twitter account, but kept insisting he was going to delete it.

Before #Bretbug, I was a tenured professor at GWU. I had written two books about digital politics and was in the middle of a new project on the history of the digital future. I liked to make snarky jokes on Twitter in my spare time. I had about 8,000 Twitter followers.

After #Bretbug, Stephens still has the same job and the same social position. His Twitter account is deleted. He has written at least a half-dozen columns that were clearly worse than the Twitter-liberals-are-nazi-propagandist column. The nickname stuck — when people make fun of him on social media, they still call him a bedbug sometimes. The episode is memorialized on his Wikipedia page.

After #Bretbug, I also have the same job and the same social position. I have about 40,000 Twitter followers. I’m still working on that digital future book project — I’ve started working out some of the bigger ideas through this Substack. I tried to get Twitter-verified a few months ago. No luck. I don’t even have a wikipedia page. Internet-fame is fun, but it’s fleeting.

The theme here is that winning the attention war is a hollow victory. If you want real wins that last, then you’re going to need to focus on structural power. Shame, ridicule, and attention can be powerful tools. But they don’t amount to anything in the long run unless you enact a plan to change the broader structures.

In this specific case, of course Bret Stephens’s bad week didn’t matter in the grander scheme of things. The whole thing was silly and absurd. Why should it matter?

But it’s a strong reminder of the difference between communication power and structural power. Convincing the public that Bret Stephens is an irritant that, try as they might, the New York Times newsroom just can’t get rid of (kind of like a… a… well, you know) is one thing. But memories fade, while structural advantages stick around.

In a class on strategic political communication, I constantly remind my students that it is never enough to “educate the public about X.” Public awareness is a leaky bucket. It can be a useful start, but you’ll never be finished with it.

If you want to make real change, you need to study the power structure, find a leverage point, make a plan, and push.

Otherwise, even in victory, you’ll look back and notice that the nothing much is different.

Those are my lessons-from-Bretbug notes. Thanks for reading. Next week I’ll be back to writing about how today’s digital future is eerily similar to the digital future we were promised 10, 20, 30 years ago.

Thanks for that article. Somehow I missed that entire "news" event, but learning about Schattschneider and the tactics you used was fascinating. It's really eye opening that, despite Stephens being a conservative, he doesn't understand this strategy for conflict. However, it seems that conservatives in general have been doing this for four decades now while liberals are the ones trying to win an academic debate that a large swath of the voting public doesn't care about. Or at least doesn't care who has the most thoughtful, rational argument.

Unfortunately, while communication power isn't structural power, it can often lead to structural power. As seen in voting shifts due to this communication strategy that lead to things like the power to gerrymander or change the balance of the supreme court. It's somewhat reductive but there's a certain amount of truth in the fact that, if the Democrats started playing the game like the way you just played it, rather than trying to win a debate club contest, they might lose the moral high ground, but they'd also gain more real power.

David, as someone that left activism after several similar events (Bill O'Reilly threatening to lead a mob to my house; Fox News corporate counsel writing my law school Dean to suggest I should be expelled for want of character; stunts that got me on Colbert and The Daily Show; countless talk radio exploits that "crossed-over" into blogs and online magazines), I cannot agree more with your close. (Though I did end up with a wikipedia page, and trust me... it's more trouble than it's worth, lol).

Anyway, I've moved on from political activism to criminal defense. I may not be able to change the world in broad strokes, but man... I can do wonders when it comes to making sure none of my clients are ever in the NYT as one of those being released from prison twenty years after being wrongfully convicted.