I was in San Francisco on Tuesday for WIRED magazine’s 30th anniversary event.

I spent most of the time scribbling notes to myself about future writing ideas. (This, tbh, is my idea of a good time. You know I’m having fun at a party if you see me in the corner, furiously tapping away at my phone’s notes app).

I left with three observations that I think are worth sharing. The main theme among all of them concerns the shifting centers of gravity in Silicon Valley, futurism, and WIRED itself:

(1) The first panel I attended featured Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, along with his colleague John Bruce at Inrupt. Inrupt is a pretty cool effort to build interoperability into the technical layers of the Internet. Berners-Lee is trying to restore the ethos of the open web by creating a system that gives users more control over their own data, thus taking power away from Facebook and Google.

I’ve heard bits and pieces about the project for years now. It seems like a fundamentally good, well-intentioned, well-designed effort. But the most striking thing about it is the sheer David-vs-Goliath nature of the task. I mean, I wish them well! But it seems pretty unlikely that we’re going to shift power away from the platforms just by building a better/fairer system and hoping it will beat the entrenched incumbent players.

And that’s what I found myself dwelling on during the panel: this is Sir Tim Berners-Lee we’re talking about here! This isn’t some young coder or upstart entrepreneur. Berners-Lee was knighted for a very good reason! There are no figures held in higher regard at the protocol layer of the web.

It’s a testament, I think, to how power online has shifted in the past couple decades. The Internet of the 1970s-90s was pretty significantly shaped by collaboration among computer scientists. They believed in “rough consensus and running code.” Groups like the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and the Internet Engineering Task Force made critical decisions that were resolved at long technical meetings. (Laura Denardis has written several excellent books about these groups. It’s fascinating stuff.)

Those were voluntary associations, and they were the center of gravity throughout the late 20th century. They were where the real, substantive decisions were made. If you think the current system had a major problem, then you could build something better and convince your peers to adopt that same standard. Tim Berners-Lee is no radical outsider or has-been in those circles. He has earned the respect of his peers. His words carried weight.

Those institutions still exist today, but they are no longer the center of gravity. I’m not precisely sure when the shift happened, but I think it was around 2008-09.

2008-09 was roughly when Web 2.0 peaked. The VC class had gotten over the post-dotcom crash doldrums, and was starting to make serious money again. And also, importantly, the 2008 economic crash led a bunch of finance-types to conclude that the way to make big money was to head to Silicon Valley instead of Wall Street. (This was the second great migration of finance-types into tech. The first was post-1995 Netscape IPO.)

Incidentally, 2008-09 was also when the W3C started working out the details of their shared vision of “Web 3.0." Web 3.0 was going to be a Semantic Web. I remember attending a big conference in Athens that year, where all the technical people were discussing their efforts to add a layer of metadata to everything that would make the entire web machine-readable.

The semantic web was a very big deal among the engineers and computer scientists who developed the protocols that created the Internet. But it didn’t move the needle for the Venture Capitalists, or the platforms, or the finance-types. And so it just sort of quietly faded away.

Then, a decade or so later, the VCs and finance-types declared their own version of Web3. Their Web3 was a blockchain moneygrab. Hell, even the true believers thought that what would make Web3 good was that the platforms were scooping up all the money, and Web3 would let the rest of us (particularly early adopters who HODL) scoop that money up instead. And their version Web3 worked very well as branding. Journalists and the mass public accepted that it was a thing. It didn’t work so well as product because it was three ponzi schemes in a trenchcoat. But, still, it provides a reminder of who calls the shots these days.

It was a bit disconcerting, watching the literal inventor of the World Wide Web on stage and recognizing that, somewhere along the way, he became sort of an outsider. He’s a celebrated, legendary figure. And his legacy hasn’t been tainted by scandal or anything like that. In any other field, a figure like Tim Berners-Lee would be the consummate insider. (Think, for instance, of how Larry Summers is treated within the halls of power. But multiply his initial influence by 50. Tim Berners-Lee ought to be fifty times the insider that Larry Summers is.)

But the center of gravity shifted as Big Tech got so big. The technical people no longer hold the power they once did. And that’s just a real shame. They were far from perfect, but they had (I think) better values and institutional practices than the VC class that sidelined and replaced them.

(2) I attended a couple of panels that offered dueling takes on futurism as an intellectual project.

First was “The Next 30: A Brief History of Our Future Unveiled.” This was a panel about the forthcoming PBS documentary series, A Brief History of the Future. The core premise of this series is going to be “challenging dystopian narratives and offering pragmatic solutions to the challenges we may face in the next 30 years.”

I am definitely going to watch this series, but I am probably going to be cranky about it. Because, on the one hand, I would love to watch a series about pragmatic solutions to the problems we face as a society. But I’m catching a strong whiff of old-school techno-optimism from the framing, and I suspect it’s gonna be another retread of the tired ‘90s school of thought.

Ari Wallach is the host of the show, and he explained on stage how he thinks the problem we face today is that we don’t tell enough optimistic stories about where technology is heading. Ari talked about growing up in the Bay area and attending Global Business Network events (they’re the folks who wrote The Long Boom). He thinks that kind of optimism was vital, that it has gone out of style, and that we need to embrace it again.

Not to turn this into another Dave-rants-about-tech-optimism post but… Did it ever really go out of style? It seems to me that the market for techno-optimistic storytelling is self-renewing. If anything, the market for that kind of storytelling has increased as the audience of potential tech billionaire-patrons has expanded. (You wanna make serious money writing about the tech future? Don’t join us Luddites. Tell rich people that everything is going great.)

Two hours later, the “SciFi IRL” panel took place on the same stage. And this panel was great! I’m hoping there will eventually be a livestream recording I can share. Annalee Newitz, Charlie Jane Anders, and Yudhanjaya Wijeratne had quite a different take on futurism. All three said they engage in futurism in some of their nonfiction writing (Anders called it a “side hustle”). And they each had serious, nuanced thoughts to offer about how you write about a future that isn’t going to be great, but still offers readers a measure of realistic hope.

I’ve been tinkering for a few weeks on a longer futurism essay, so I’ll save some of the deep-dive points for that. But I find it remarkably striking how well these sci-fi authors have developed an approach to the future that rejects doomerism without being saccharine or insisting that readers just assume that everything will turn out alright.

(Also, since ‘tis the season: you should absolutely buy these authors’ books for someone you love.)

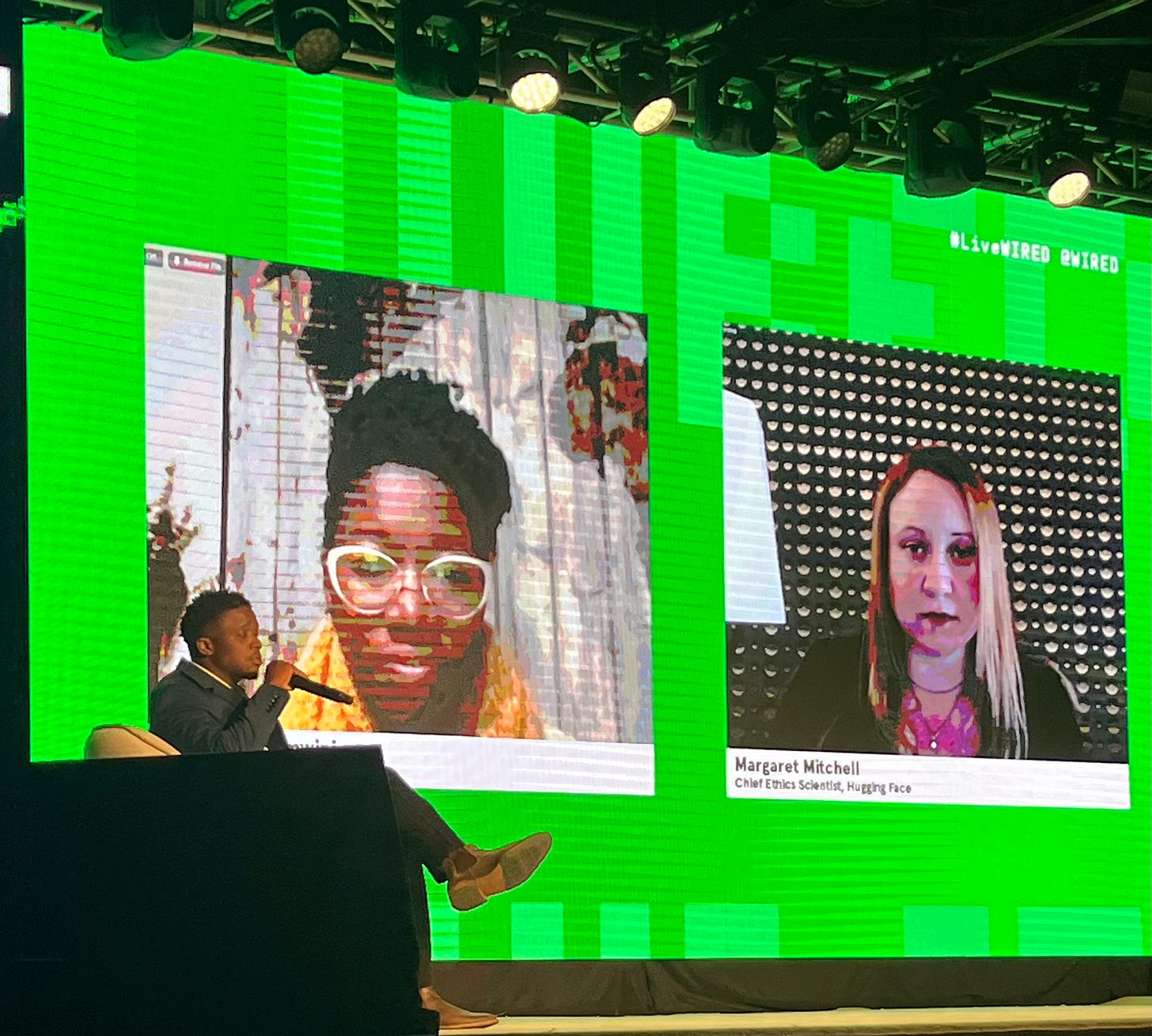

(3) There were a few panels that covered generative AI — a lunchtime “AI Optimist’s Club” panel, featuring Reid Hoffman and Fei-Fei Li, an AI Ethics panel with Margaret Mitchell and Dr. Joy Buolamwini, and an IP vs AI panel with Mike Masnick, Matthew Butterick, and Mary Rasenberger. Jaron Lanier also spoke about AI a fair amount during the closing keynote.

What stood out to me was what this collection of panels was signaling about the boundary lines that WIRED is trying to draw around the AI debate — Think of it as WIRED editorial leadership establishing parameters for their Overton window preferences.

The most-enthusiastic people on stage were Hoffman and Li. And, honestly, they talked a lot of sense. I’d characterize Reid Hoffman’s position as “this is shaping up to be a general purpose technology with a ton of useful applications. It could make a ton of money while solving a bunch of problems. It’s also going to require new regulations as it develops.” His main response to the existential risk arguments was (paraphrasing here) “I think you’re right that people are bad at imagining how systems will change when we’re on an exponential growth curve. But then you tell me how confident you are about the changes that are about to happen, and I want to refer you back to your earlier point.”

Notably absent were any AI existential-risk/longtermists, or any effective accelerationists or transhumanists. Kevin Kelly wrote a rose-colored-glasses cover story about AI for WIRED last year, “Picture limitless creativity at your fingertips,” that was dismissive about the downsides of the technology for professional artists. Kelly didn’t attend the conference, and no one else was brought in to represent the techno-optimist perspective in his stead. Instead we had a couple of lawyers representing authors and artists, arguing with Masnick over whether LLM scraping is going to be covered by the Fair Use Doctrine.

I have two takeaways from this boundary-drawing:

These are approximately where I would set the boundaries of reasonable debate. Yeah, sure, there are a bunch of market opportunities and potential use cases. I think a well-regulated marketplace could lead a bunch of companies to develop a bunch of products that could work quite well. But we need to pay serious attention to the flaws and limitations in these large language models. This stuff is error-ridden and set to amplify a metric ton of social harms if we leave the companies to set their own rules while chasing profits in regulatory grayzones.

These are absolutely not the boundaries that Old-WIRED would have drawn. I mean, take a look at this picture of the AI Ethics panel. Khari Johnson, interviewing Dr. Joy Buolamwini and Margaret Mitchell. These are (on, uh several levels), not voices or perspectives that appeared in the magazine over its first ten years. And that’s a good thing. It’s part of what makes me like current-WIRED more than old-WIRED. It takes the serious critics seriously, and gives them a place on the stage instead of trying to wish them out of existence.

One final, related point is that the event didn’t have the feel of an anniversary-milestone party. The ideal-type for anniversary events is to gather the community associated with an institution, pay homage to your accomplishments, and then look toward the future. This felt more like an in-person event that happened to have “the next 30 years” as a uniting theme. There wasn’t a lot of stage-time devoted to the magazine’s history (there were a couple of very cool art exhibits though), or highlighting past contributors.

The reason, I think, is twofold.

First, there isn’t a “WIRED community.” Not really, at least. WIRED is a magazine. Its most important contributors over the decades were journalists, doing their dayjobs. When they left, they took different dayjobs — sometimes at rival publications, sometimes in different fields entirely.

The people in attendance weren’t, for the most part, past WIRED contributors or diehard readers of the magazine. The attendees were mostly San Francisco tech-adjacent folks with flexible enough schedules that they could spend the day at an interesting conference.

In WIRED’s early years, I think there absolutely was a WIRED community. It was an offshoot of the WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link). Nearly all of WIRED’s earliest writers came out of the WELL. And WIRED in the 90s was a self-styled pirate ship, with strong ideological commitments and a sense that it was taking on the old guard and winning.

Present-day WIRED is no longer committed to the ideology that suffused the original magazine. And that’s the second reason — it isn’t clear what elements of the magazine’s 30-year history most deserve to be celebrated today. The techno-optimist ideology that old WIRED represented managed to become dominant in tech. They amassed fortunes. And things didn’t turn out nearly as well as they insisted it would.

Today’s magazine is focused on reporting and assessing how things are going today, and that includes reporting on the shadows cast by the success of the old WIRED ideology. There’s an irresolvable tension there, I think.

So that all added up to an anniversary event that felt kind of like a birthday party for someone who doesn’t like birthdays. (“Okay, sure, we can gather a bunch of friends. But no candles, no cake, no singing, and let’s please find something more interesting to talk about!”)

I’m glad I had the chance to go; I wonder what #WIRED35 will be like.

I think my topline summary of all of this is that "follow the money" remains the only reliable directive toward understanding how things got to where they are and where they're probably going. Berners-Lee is sort of sidelined because what he's doing doesn't stand to make any dude (or any small group of dudes) a metric ton of money. Dystopian narratives about the future dominate because they center the path of least resistance with respect to how things will go if/when making a small group of dudes a metric ton of money is the core driver. And the conversation around generative AI is sort of frustrating/scary/disorienting because while AI will likely make some things more convenient and maybe even, in some cases, more creative, we can be confident that all of that will be around the margins of use cases and a regulatory/policy environment that enables... a few dudes to make a metric ton of money.

This was a very interesting read! I think there's even an interesting parallel to be made with the rise of VCs/sidelining of technical people, and the reduced ideology and influence of communities like those around WIRED like you pointed out at the end.

When you say the old WIRED community, from the WELL-era, is gone, that reads as part of the same phenomenon -- the sidelining and reduction of technical people (around a media outlet) who were doing a lot of public agenda-setting and were far from perfect, but at least less sinister than the VC community that came after (paraphrasing your point a bit).

I wonder if there might be a modern analogue to such communities or media outlets? Or maybe with the fragmentation of online culture and dwindling trust, media outlets are just too irrelevant now and having an ideology/community around them is just not possible?