Elon Musk and the Infinite Rebuy

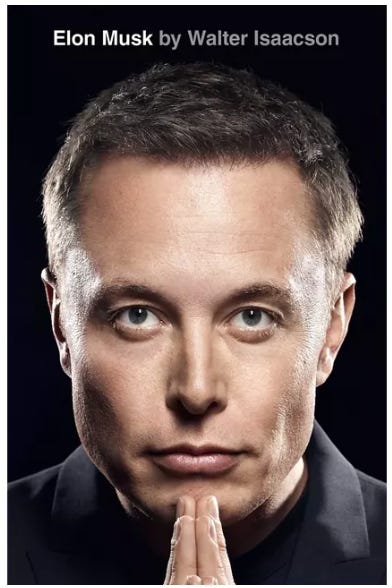

Walter Isaacson tried to write a "Great Man" biography of the rockets-and-cars genius. That's not an effective way to understand Elon Musk.

[adapted from the exceptionally-long Bluesky thread where I livetweeted my way through this shoddy book]

There’s a scene in Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Elon Musk that unintentionally captures the essence of the book:

[Max] Levchin was at a friend’s bachelor pad hanging out with Musk. Some people were playing a high-stakes game of Texas Hold ‘Em. Although Musk was not a card player, he pulled up to the table. “There were all these nerds and sharpsters who were good at memorizing cards and calculating odds,” Levchin says. “Elon just proceeded to go all in on every hand and lose. Then he would buy more chips and double down. Eventually, after losing many hands, he went all in and won. Then he said “Right, fine, I’m done.” It would be a theme in his life: avoid taking chips off the table; keep risking them.

That would turn out to be a good strategy. (page 86)

There are a couple ways you can read this scene. One is that Musk is an aggressive risk-taker who defies convention, blazes his own path, and routinely proves his doubters wrong.

The other is that Elon Musk sucks at poker. But he has access to so much capital that he can keep rebuying until he scores a win.

Isaacson, our narrator, doesn’t grasp the difference. He doesn’t understand poker well enough to recognize Musk as the grandstanding sucker at the table. So he portrays Musk’s complete lack of impulse control as a brilliant, identity-defining strategic ploy. (If you go all-in and lose six times, then go all-in a seventh time and win, then you’re still down five buy-ins.)

Isaacson clearly knew what sort of book he was setting out to write. He is a star biographer, one who specializes in penning classic, “Great Man” stories of history-defining figures. He has chronicled the lives of Ben Franklin, Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, and others.

The motivating premise of these “Great Man” stories is that history is made by unrestrained, risk-taking geniuses. Isaacson strives to give his readers insights into the complex inner lives of these singular, special individuals: what drives them, where they come from, what they have figured out that positioned them to make such a dent in the universe?

The “Great Man” version of history is always limiting (and, as Brian Merchant argues, it should probably be retired at this point), but it is particularly ill-suited to a character like Musk. Isaacson wants his reader to appreciate Musk’s accomplishments and also ponder his personal “demons.” But there is a deeper puzzle that Isaacson constantly avoids “Is Elon Musk really some world-bending genius, or has he just benefitted from the world’s biggest case of survivor bias?”

That’s not a question that Isaacson is comfortable assessing. And so he brazens past all the warning signs, attributes every self-destructive act to a tough childhood or a mean girlfriend, and faithfully reproduces for his readers the view-from-Musk. The result is a bland, trite, uninteresting book, one that is destined to be remembered as the worst of Isaacson’s long career (the negative reviews have been delicious).

There is a worthwhile biography still to-be-written about Elon Musk. But it will require a biographer with a sharper eye, a more discerning ear and a more tenacious voice.

The first sign of trouble shows up on page 1 of the prologue. Isaacson opens with an anecdote from Musk’s troubled childhood, relating a story from when Elon was twelve and he was sent to veldskool, a wilderness survival camp:

“The kids were each given small rations of food and water, and they were allowed—indeed encouraged— to fight over them. (…) Near the end of the first week the boys were divided into two groups and told to attack each other. (…) Every few years, one of the kids would die.” (page 2)

The intent of this anecdote is to relate how, when Musk went back to veldskool at age sixteen, he realized he was too-big-to-bully. Isaacson uses this scene to impress upon his readers that (1) Elon learned at an early age that you have to fight to survive, (2) he carries the scars of that childhood with him today, and (3) it drives him to want to control and dominate every situation.

It’s an unbelievable story. And by that, I mean I don’t entirely believe it. Musk grew up rich and white in apartheid-era South Africa. Are you really telling me that rich white kids in South Africa were repeatedly dying, and the camp stayed open?

If veldskool left a trail of child corpses, it would’ve been covered in the newspapers. That’s something a reporter could easily track down. Instead, Isaacson merely confirms the anecdote with Musk’s brother (and frequent business partner) Kimball. Elon says it happened that way. Kimball says it happened that way. Maybe they’re exaggerating a bit, but it’s still a great anecdote!

This marks a fundamental problem that pops up throughout the book: (1) Musk is a serial liar. (2) Isaacson seems utterly disinterested in investigating whether anything Musk says is particularly true.

This authorial disinterest renders the early chapters unreliable. Isaacson retells the story of Musk’s difficult childhood as Musk himself would like it told. The narrative beats here are pretty well-known: he was bullied as a child. His father was emotionally abusive. His father had an ownership in a emerald mine, but kinda not really. He moved to Canada and started with little money. He got decent grades at Queen’s University in Canada, then transferred to Penn. He double-majored at Penn, got into Stanford’s PhD program, dropped out to join the Silicon Valley gold rush. etc etc etc. Musk himself has told this story to a hundred reporters, always with slight variations and embellishments as suited his mood at the time.

Which parts of this story are actually true? Which parts just feel true to Musk today? And which parts are convenient narrative devices? We have no real way of knowing, because Isaacson views his job as establishing a proper “Great Man” origin story.

One omission that caught my eye concerned Musk’s undergraduate degree. This has been the subject of substantial controversy, and factored into at least two lawsuits. Isaacson says Musk graduated from Penn in 1995. We know for a fact that he left Penn in 1995, but his undergraduate degree is dated May 1997. Musk insists that this was basically a clerical error (He had “agreed with Penn” that he would satisfy his History and English credits at Stanford, but then he dropped out of Stanford and forgot about the whole matter for a couple years). Critics charge that he lied about his academic credentials, hustled his way through mid-90s Silicon Valley on an expired visa, and then asked a well-connected investors to tidy things up and get the credits waived by Penn.

It seems like something a biographer ought to take the time to nail down: Did Musk drop out of college, lie on his resume to get a head start in Silicon Valley, and then pull some strings to get it all cleared up? Or did the University of Pennsylvania administrative bureaucracy tell an at-the-time-unremarkable international transfer student, “sure, that’s fine, just finish your degree requirements at a competing university and we’ll mail you the degree. We don’t really want those extra tuition dollars from you.”

Musk’s first biographer, Ashlee Vance, asked Elon about it. Elon spun an elaborate tale, which Vance found persuasive. Isaacson doesn’t even bother to ask. He doesn’t even acknowledge the discrepancy or mention the controversy. Elon’s youth was whatever Elon and his friends say it was.

I imagine part of the reason Isaacson doesn’t pick at this knot is that young-Elon already isn’t fitting the mold for the standard world-changing-genius origin story. He got A’s and B’s in his classes and did little to distinguish himself. He showed some gifts as a computer programmer, but nothing particularly noteworthy. (he coded his own computer game in the 1980s. I had two friends in my public high school who did the same thing, and I wasn’t even hanging out with the computer club.) There is nothing in his youthful biography, with the exception of the extreme bullying and the awful father, that made him any different from all the other computer geeks of that era. There is little in the narrative that would lead one to think Musk possesses some special spark, vision, or insight that is setting him up for greatness.

But he must be great. Look at all that money and all those companies!

Musk flipped his first company (Zip2) for a profit back in the early internet boom years, when it was easy to flip your company for a profit.

He was ousted as CEO of his second company (PayPal). It succeeded in spite of him. He was still the largest shareholder when it was sold to eBay, which netted him $175 million for a company whose key move was removing him from leadership.

He invested the PayPal windfall into SpaceX, and burned through all of SpaceX’s capital without successfully launching a single rocket. The first three rockets all blew up, at least partially because Musk-the-manager insisted on cutting the wrong corners. He only had the budget to try three times. In 2008 SpaceX was spiraling toward bankruptcy.

The company was rescued by Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund (which was populated bybasically the whole rest of the “PayPal mafia”). These were the same people who had firsthand knowledge of Musk-the-impetuous-and-destructive-CEO. There’s a fascinating scene in the book, where Thiel asks Musk if he can speak with the company’s chief rocket engineer. Elon replies “you’re speaking to him right now.”

That’s, uh, not reassuring to Thiel and his crew. They had worked with Musk. They know he isn’t an ACTUAL rocket scientist. They also know he’s a control freak with at-times-awful instincts. SpaceX employs plenty of rocket scientists with Ph.D.’s. But Elon is always gonna Elon. The “real world Tony Stark” vibe is an illusion, but one that he desperately seeks to maintain, even when his company is on the line and his audience knows better.

Founders Fund invests $20 million anyway, effectively saving the company. The investment wasn’t because they believed human civilization has to become multiplanetary, or even because they were confident the fourth rocket launch would go better than the first three. It was because they felt guilty about firing Elon back in the PayPal days, and they figured there would be a lot of money in it if the longshot bet paid off. They spotted Elon another buy-in. He went all-in again. And this time the rocket launch was a success.

If you want to be hailed as a genius innovator, you don’t actually need next-level brilliance. You just need access to enough money to keep rebuying until you succeed.

Isaacson goes into great detail about Musk’s management philosophy — his “production algorithm”: (1) Question every requirement, (2) Delete any part or process you can, (3) Simplify and optimize, (4) Accelerate cycle time, (5) Automate.

(Also, “All technical managers must have hands-on experience,” “comradery is dangerous,” “It’s OK to be wrong. Just don’t be confident and wrong.” “Never ask your troops to do something you’re not willing to do.” “Whenever there are problems to solve, don’t just meet with your managers.” “When hiring, look for people with the right attitude.” “A maniacal sense of urgency is our operating principle.” “The only rules are the ones dictated by the laws of physics. Everything else is a recommendation.”

Isaacson elevates this philosophy to vaunted status. This is supposed to be the skeleton key that explains, despite all his personal flaws and demons, why Musk is such a transformative figure.

There are bits to admire here. Musk’s focus on efficiency seems to have lowered the cost of space flight. Putting engineers close to the production lines helps them identify hidden bottlenecks. Small teams of inspired, talented people can accomplish a lot if they are given a deadline and a sense of urgency.

But it often seems like what Isaacson finds most appealing about Musk is that he treats rules and regulations as somebody else’s problem. You can accomplish a lot if you just decide that none of the safety regulations apply to you. (What’s the worst that can happen? A rocket blows up? A driverless car kills someone? Some employees are maimed? We’re inventing the future here. Let’s be bold and insist someone else pays for the damages.)

It’s not just that Musk is constantly, at an individual level, a complete asshole to his employees. Injury rates at Tesla factories were 30% higher than at other car companies. We get no sense of the baseline success rate of Musk’s constant “surges,” where he forces teams work 20-hour days to meet an arbitrary deadline. It seems likely that the surges mainly serve to make Musk feel good about himself, while burning out his employees and creating a cascading litany of errors that have to be corrected later, once Musk’s attention has turned elsewhere.

Musk’s “algorithm” sounds a lot like what you would hear from any YCombinator-style startup evangelist: Simplify, iterate, pivot, hustle, pursue constant growth. If Musk’s management philosophy is the key insight separating him from everyone else, why does it sound interchangeable with every techbro podcast?

Isaacson manages to barely mention the labor issues at Tesla. And this is a noteworthy omission, given the attention he pays to Musk’s political, uh, evolution.

He writes about the 2021 White House electric car event, where Biden invites the three major car manufacturers and the UAW, but not Musk. Musk is outraged by the snub. He takes it personally. Isaacson mentions in passing that “the UAW had failed to unionize Tesla’s Fremont plant, partly because of what the NLRB deemed to be illegal anti-union actions by the company.”

It’s reasonable to suspect that part of Musk’s personal evolution is that, as his companies have gotten bigger and his wealth has soared, he has faced institutional pushback from (for instance) unions. And he has reacted by developing intensely plutocratic, authoritarian political views. Illegal anti-union actions are a problem for the Democratic party coalition. For the Republican party coalition, illegal anti-union actions are a feature, not a bug.

Elon’s philosophy is full of unexamined contradictions. He expects employees to work 20-hr days and show obsessive devotion to the job. He lectures them for not having lots of kids. He says the secret to innovation is “challenge authority.” He fires any employee who challenges him.

I’m pretty convinced that Elon believes all of the things he says. The trick to understanding the contradictions is to realize he just isn’t especially bright. …And that’s a problem for Isaacson. If he inquired deeply, the Great Man facade would slip.

This also comes up on page 241, in the origin story of Open AI. Musk is at a party with Larry Page in 2013. He starts droning in about AI replacing us. Page notes that, hypothetically, there’s nothing special about human consciousness. Maybe something comes after us. This is a pretty standard philosophical point. But Elon can’t deal with it, so he just gets mad. “Well yes, I am pro-human. I fucking like humanity, dude.” Musk leaves the conversation with a permanent grudge, convincing himself that a whole new company is necessary to compete with Google.

(Just think… in a world where Elon Musk could either (a) pass an intro-level philosophy class, or (b) didn’t have billions in spare cash to throw behind every grudge, OpenAI might never have gotten its initial seed funding!)

I had assumed that Isaacson’s biography would effectively be two books — the first, an origin story, retelling old stories as Elon and his buddies prefer them told; the second, based on firsthand reporting, spilling tea from his two years being in the room where it happened. That turned out not to be the case. The later chapters studiously maintain the view-from-Musk tone, even as Isaacson becomes increasingly disillusioned with Musk’s flailing Twitter antics.

This is where the correction Isaacson issued to the Ukraine chapter proves especially damning. It effectively invalidates the whole book project. The promise of this book — the bit that makes Isaacson something more than just a dutiful stenographer — is that he spent two years in the room, listening to Musk, watching the most powerful individual in the world as he publicly melted down.

In the Ukraine chapter, Isaacson writes that Musk “personally took charge” and “secretly told his engineers” to turn off Starlink coverage that was necessary for their planned drone strike. That’s, y’know, actual treason. So, once the excerpt is published, Musk pressures him to correct his reporting. Isaacson announces that he was just confused. The coverage was never enabled, it’s just that Ukrainians thought it was.

Isaacson interviewed no Ukrainians. He has no insight into what they thought. He only knows what Elon told him, the text message chains Elon shared with him, and what he saw firsthand.

Either you make sure you nail down your reporting, you publish your book, and you stand by what you saw, or you’re effectively nothing more than a glorified publicist. The years spent shadowing Musk amount to nothing if the details are so flimsy that they can be reconfigured upon command.

The whole narrative begins to unravel in the last 150 or so pages, once the Twitter drama takes center stage. Isaacson tries his best to justify Musk’s obsession, writing:

[on Twitter] the clever kids win followers rather than get pushed down the concrete steps. And if you’re the richest and cleverest of all, you can even decide, unlike back when you were a kid, to become king of the schoolyard.

The gaping flaw in this analogy, of course, is that clever has nothing to do with it. If the most-clever users got to run Twitter, then Dril would be Twitter CEO! Elon recycles Reddit memes. His jokes are stale. He became obsessed with Twitter because he has no impulse control, not because he was a world-class poster.

The entire story of Elon Musk buying Twitter is that he is a centi-billionaire with no impulse control. (The night before he submitted an offer to buy Twitter, he stayed up until 5:30am playing Elden Ring. Who among us hasn’t stayed up all night playing a video game and then impulse-bought a $44 billion dollar company?)

He wanted Twitter, so he bought Twitter on a whim. Because he could. Because being that rich means you can keep pushing all your chips into the middle. You have enough money for infinite rebuys.

(Then Musk tries to back out of the purchase, and learns that the Delaware Chancery Court does not believe merger contracts are “just recommendations.”)

Elon enters Twitter and immediately tries to run it like SpaceX and Tesla. And that doesn’t work at all because why the hell would it? This is a huge problem for Isaacson’s narrative, because if Musk’s “production algorithm” is a trash fire at Twitter, then maybe it isn’t so uniquely special after all. Maybe Musk was an unremarkable-but-hardworking businessman who had two improbable bets turn out in his favor, thus acquiring so much money and influence that he became immune to consequences.

That’s a story of good fortune, not a story of inherent greatness.

It seems clear that Isaacson desperately wishes the Twitter deal hadn’t happened. He set out to write about the car-and-rocket guy… The rich guy who is taking risks and building the future! He doesn’t want to write about the plutocrat with no impulse control and no clue.

The last 100 pages of the book are almost all Twitter stories. And the remarkable thing is that, even though Isaacson was IN THE ROOM, they still read like a bland ChatGPT-summary of Casey Newton’s reporting.

Musk, as I’ve mentioned, is a lousy card player. But Isaacson is clearly the sucker at the table. He writes that, just days before the Twitter acquisition, Parag Agarwal spoke positively about the opportunity to work with Elon: “he was being guarded, but I think he believed it.”

All Isaacson needed to do was read contemporaneous reporting to realize otherwise. EVERYONE knew Agarwal was immediately going to be fired. EVERYONE knew he would walk away with a $50 million severance package. Agarwal was speaking in the bland, lawyered voice of someone waiting for the ink to dry.

This points to a larger issue in the book. Musk is a vindictive asshole. Isaacson says so himself. But Isaacson also repeatedly leans on words of polite support from people in Musk’s orbit to demonstrate what a Great, Visionary Man he is. He has no ear for half-hearted, cover-your-ass praise.

How many of the actual rocket scientists working at SpaceX, when they tell Isaacson, ”oh yeah my vindictive billionaire boss with a business degree and no impulse control absolutely has unique, helpful insights into physics and material science” are dutifully repeating the phrases that keep them employed? “Great Man” histories are more reliable when the subjects are already long deceased and can seek no retribution.

Ultimately, the trouble with Elon Musk (the book) is that Elon Musk (the man) doesn’t easily fit into the “Great Man” template. On paper, he ought to. He is the world’s richest man. He’s the CEO of companies that have restructured two major industries. He is a flawed, colorful character. If, a few years ago, you were scanning the ranks of Silicon Valley billionaires, asking which one had the most interesting stories to tell, it would be hard to settle on anyone other than Musk.

There are even a few stylistic similarities between Musk and Isaacson’s other most famous biographical subject, Steve Jobs. The temper. The ambition. The “reality distortion field.” Musk’s single greatest success is, I suppose, somewhat Jobs-ian. Steve Jobs had a gift for convincing journalists and adoring consumers that his company’s products were the future. Musk, too, has undeniably influenced how journalists and the public talk about electric cars and space flight.

But the similarities fall apart upon extended exposure. Musk’s design sensibilities are atrocious (*cough* Cybertruck *cough*). Jobs, for all his faults, matured as he aged. Musk, just earlier this year, was vindicated in a lawsuit under the legal defense that “[52 year old] Elon Musk is just an impulsive kid with a terrible Twitter habit.”

And then, of course, there’s the Twitter fiasco. Walter Isaacson set out to write a book about the fascinating rockets-and-cars innovator. He tries, throughout the book, to fashion a picture of the troubled and troubling genius who insists on only being bound by the laws of physics (everything else is “just a recommendation”). But, hard as he tries, Isaacson just never manages to make Musk look like anything all that special.

Part of the problem is that Musk never satisfies himself with being hailed as the next Steve Jobs. He insists on being lauded as the next Steve Wozniak as well. And he just, plainly, isn’t. Not even Walter Isaacson can sell that image.

The book concludes by attempting to make a metaphor out of the Starship launch. Musk ignores all regulations, because they stifle his ambitions and he’s too big to be bothered. Starship takes off… and then blows up. There’s success, but also tons of damage. Isaacson, as he does throughout the book, diverts our attention from the damage. He asks us instead to consider it a trade off.

Isaacson’s model of society is that history is written by unrestrained, risk-taking geniuses. That’s the type of biography he set out to write. He doesn’t much like Musk, because Musk won’t fit into the archetype.

But it’s the only story Isaacson is equipped to tell.

My god, but that really is a telling story, that Isaacson tells the poker story as a story of winning and resolve rather than as a story of stupidity protected by an infinite bankroll. In poker terms, that makes Musk a fish. And one thing hardcore poker players love is the fish who gets up from the table and tells a story of himself as triumphant; that makes the fish not the one that got away but the one that will come back eventually. In one story, Isaacson could remake the narrative: Musk is someone who has always had such a deep bankroll that he could walk away from any table saying that he won, and eventually buy enough people who found him a valuable fish that they'd stake him some more just to keep him coming back.

I love how some games show people for who they really are:

Elon pretending he can compete in poker by going all-in on every hand and buying back until he finally wins a pot.

Trump pretending he can compete in golf because he can always find someone willing to sign his scorecard and attest that he didn’t cheat.