There is a sparseness to Alex Garland’s new movie, Civil War. The film feels like a blunt object. It is brutal, harrowing. It bludgeons the viewer with a single, message: it could happen here.

It is a very good movie.

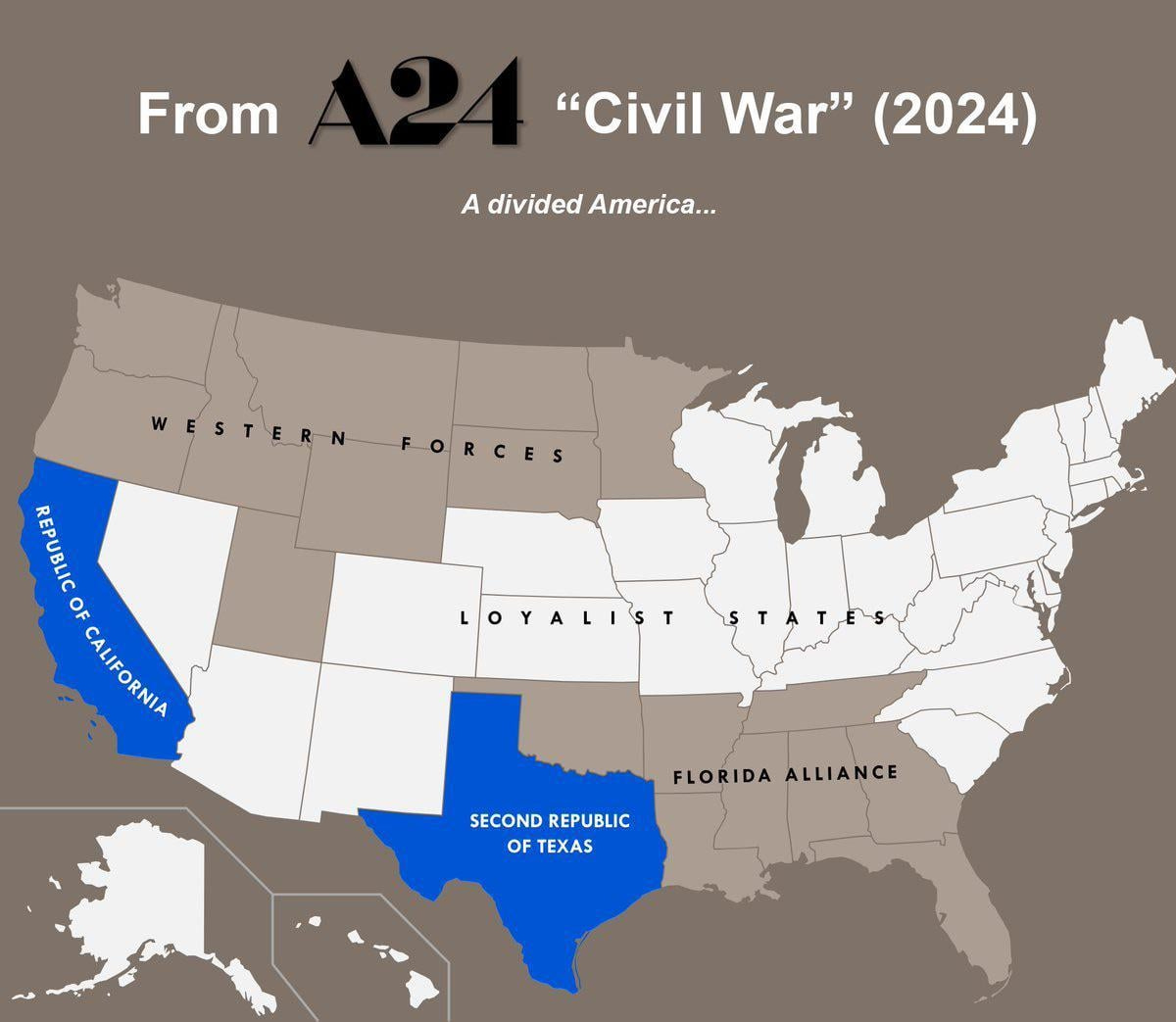

The film has attracted a fair amount of criticism for what it doesn’t do. There is a complete lack of political worldbuilding in the movie. It is set in the near future, in a United States that is not quite ours. There are no MAGA hats, but there is a reference to the “antifa massacre.” There is no Trump, but there is a third-term President who speaks in a Trump-y cadence. We are never told what events precipitated the civil war, nor what the generals believe they are fighting over. A24 released a map of the “divided America” and it lacks any rhyme or reason.

But that’s fine. It just isn’t that sort of film.

The film’s protagonists are photojournalists. We follow them on a road trip from New York City to Washington, D.C., detouring through Pittsburgh and West Virginia. The plot isn’t much more than a series of vignettes — the horrors and senselessness of war, against a backdrop that feels distinctly like here instead of over there.

These aren’t investigative reporters, trying to unravel some grand conspiracy or solve a mystery about the war’s origins. The main characters are protagonists, not heroes. They are weary, worn out, threadbare. Their motivation is to document the violent conflict. (For whom? Through what residual media apparatus? To what end?) The aren’t there to forestall a tragedy. When they encounter people being tortured or waiting to be executed, they respond by snapping a photo. They are driven to tell this story because it’s the only story left to tell.

We get very little worldbuilding, because the film isn’t a cautionary tale about how-we-got-here. It’s a cautionary tale about just how bad here actually is. I think Max Read summarized it perfectly: “what if 2007 Iraq happened in Pennsylvania?”

The result is a film that rattles you. They blow up the Lincoln Memorial, and the viewer is not given an ethical compass of good-guys and bad-guys from which to make sense of it. We know, intellectually, that civil wars are like this. But there is a visceral quality to seeing it in a setting that is so recognizably here, without the comfort of being able to focus on some other plot development or stakes or intrigue.

It is a film about the horrors of war, but here. And that is all the film is about. It refuses to add any other elements that would draw our attention away from that singular focus. Alex Garland is a skillful director, and the acting is goddamn excellent.

It leaves a mark. The bludgeoning is the point, and it is a point well-made.

What I appreciated about the film is that it articulates something that I often find myself reaching for.

I teach Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals every semester. The midterm in one of my classes is a campaign planning exercise. I try to help my students think about power structures, and how you apply pressure to them.

About once a year, I’ll have a proper firebrand-leftist in the class. Someone who sees the rot at the core of the political system, and is ready to burn it all down. I like the campus radicals, even though I never was one of them. I particularly like it when they take my class. They make the class discussion so much better.

But one point that I always try to impress upon them is that the revolution, if it were to come, won’t be anything like they imagine. I am pretty confident that I, for one, would perish if civil society collapsed. I have no combat skills. I can write a mean blog post and deliver a hell of a lecture once I have a good head of steam. But that amounts to much in a conflict zone. Best I can tell, it would put a target on my back.

There’s a passage in Rules for Radicals where Alinsky talks about Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience. He dismisses the high-minded principles, instead treating it as a strategic imperative: When your opponents have the guns, you really ought to develop tactics that turn your lack-of-guns into an asset.

The United States is awash in deadly weapons. And those weapons are not evenly distributed across ideological lines. The people who buy guns tend to wear MAGA hats. The people who join police forces also tend to wear MAGA hats on their days off, by the way. It is a pretty awful status quo.

I understand the revolutionary impulse. American Democracy is built upon a rotten foundation of white supremacy. Reform efforts are hard, and slow, and always incomplete. The idea that we ought to defend and hold up a fundamentally unjust system — that we should support a social hierarchy that violently oppresses vulnerable populations — is barely-defensible in the abstract.

And yet, if we were to tear the existing social order down to the studs, that would also mean grappling with well-armed white supremacists, who have their own plans for who and how the law ought to protect and bind.

I remain anchored in reformist politics, convinced that we need somehow to manage to improve an unjust political system while also strengthening the institutions of civil society. And the reason is because of my conviction that a breakdown of the social order would be much worse, and its impacts would be delivered most forcefully to the people who are already routinely scapegoated and attacked.

But I’m not sure how well this message ever comes through. There is something abstract in my rendering of it.

Garland’s Civil War delivers that warning with a bluntness and heft that my Alinsky class discussions never can. This is what it would be like. Sit with it. Experience the anxiety and the tension. Let it rattle you. Recognize that the protagonists in such a tale have no agency to affect the outcome. They are witnesses, not heroes. All they can do is document the atrocities, hoping that someday, someone will get the message.

It is a film without answers. It doesn’t tell you how we avoid a Civil War, or who is at fault. Its task is simpler than that. More sparse.

This is what a civil war would be like. Not over there. Here.

That’s a powerful, tight message, well-suited to a film.

The message would have been diluted, I think, had Garland tried to say or do much more than that.

"And yet, if we were to tear the existing social order down to the studs, that would also mean grappling with well-armed white supremacists, who have their own plans for who and how the law ought to protect and bind. "

Excellently put, well said

"I have no combat skills."

I don't think this observation is quite to the point, because it plays to the trope that "only the strong survive" etc. The underlying fact is your later observation that as an individual, you have (almost) no agency. "In this world, a man - by himself - is nothing." No matter how much of a mean motherfucker you are, no matter how well trained or how well armed, no matter your Navy SEAL experience, whether you survive a civil war is mostly a matter of chance. Pajama Boy may well outlive you. And to the degree it is not a matter of chance, it is this: the best people die first. Those who are willing to take a risk to help others actually do suffer from that risk.

I agree with everything else though.