Bullet Points: A Few Good Reads

"Every Day, Computers Are Making People Easier to Use"

I’m in book-editing mode for the next couple of weeks. A few links-with-comments to share in the meantime:

(1) I have a new piece in The Atlantic, discussing the TikTok deal and MAGA media consolidation. (“The MAGA media takeover”)

[TL;DR version is that we have a lot more to worry about from a Trumpist oligarch-owned TikTok than we did from a ByteDance-owned TikTok. There is every reason to expect Larry Ellison and his buddies to give TikTok’s algorithm the same treatment that Elon gave Twitter. And in a moment when the government is conjuring up phantom “antifa” threats and directing the justice department to investigate Trump’s critics, the threat posed by surveillance is at an all-time high.]

(2) It seems like we should all have a mental file titled “Larry Ellison,” to go alongside the files on Elon Musk and Marc Andreessen and the rest of the tech oligarchs. Ellison is now competing for the title of world’s-richest-man. His son just bought Paramount (which owns CBS), and is preparing a bid for Warner Bros/Discovery (which owns CNN and HBO). It seems like the Ellison family watched Succession and thought the moral of the story was “be more like the Roys.”

WIRED’s Jake Lahut has the details on Ellison — who he is, what motivates him, and just how central he has become to the second Trump administration. (“Larry Ellison is a ‘Shadow President’ in Donald Trump’s America.”)

(Also, holy hell does WIRED’s latest issue look fantastic. The Kate Drummond era of WIRED continues to blow me away.)

(3) Isaac Chotiner interviewed Cass Sunstein in the New Yorker, and it is a vintage Chotining.

Most of the online commentary has focused on the end of the interview, where Chotiner asks about Sunstein’s friendship with Henry Kissinger. But the bit that I found most revealing was earlier in the interview, where Sunstein explains how his commitment to optimism has created huge blind spots in his analysis.

Sunstein’s new book, On Liberalism seeks to refashion the idea of liberalism into a tarp so wide that all nine of our current Supreme Court Justices can take shelter underneath it. Donald Trump barely receives a mention.

CHOTINER: You have chosen to write a book about liberalism at a time when liberalism is under threat without really talking about what those threats are. It’s more of a positive case for liberalism. Why did you decide to write this particular book?

SUNSTEIN: Partly it’s temperamental. Probably that’s the fundamental answer. To say that there are these people and they have names and they are doing and saying awful things would be, for me, unpleasant.

CHOTINER:Even if it’s the President?

SUNSTEIN: Even in the event that it’s the President, that’s right. I feel a little bit that it would date the book and cheapen the analysis if it was calling out the President or calling out some contemporary prominent person. But I think the more fundamental and more truthful answer is that talking about the President makes me grumpy and talking about John Stuart Mill or John Rawls makes me the opposite of grumpy.

Later in the interview, Sunstein calls this a “character failure” on his part — he tends to “accentuate the positive.” And if that means ignoring Donald Trump, or the actions of the Trumpist wing of the Republican Party, or the unsavory parts of Friedrich von Hayek’s or Murray Rothbard’s or Ronald Reagan’s work, then so be it.

It’s particularly revealing when Chotiner brings up the current Supreme Court. Sunstein just can’t bring himself to admit there is a problem. “Alito is an extremely careful lawyer and a very precise judge,” Sunstein insists. “In terms of the liberal tradition, [Sunstein is] not giving up on Justice Thomas.”

The trouble with having a bedrock intellectual commitment to optimism is what it forces you to look away from. That’s not to say everyone should be doom-and-gloom all the time. (That’s my lane. It has its own drawbacks. It is not the only one.) But I think public intellectuals like Sunstein would be well-served by a simple Bayesian exercise: what events and behaviors of the past 5-10 years have come as a surprise to you? (Or as Dan Davies put it, “If you don’t make predictions, you’ll never know what to be surprised by.”)

Cass Sunstein has been in public life for a very long time. I am certain that he is surprised by the current Supreme Court’s abuse of the shadow docket, among other things. Focusing-on-the-positive might be a formula for fast book-writing (he has written something like 60 books. Brandon Sanderson is probably jealous of that pace!), but it is also a formula for ignoring the things you’d rather not see. Do that for long enough, on a large enough stage, and you’ll eventually find yourself on the wrong side of a Chotining.

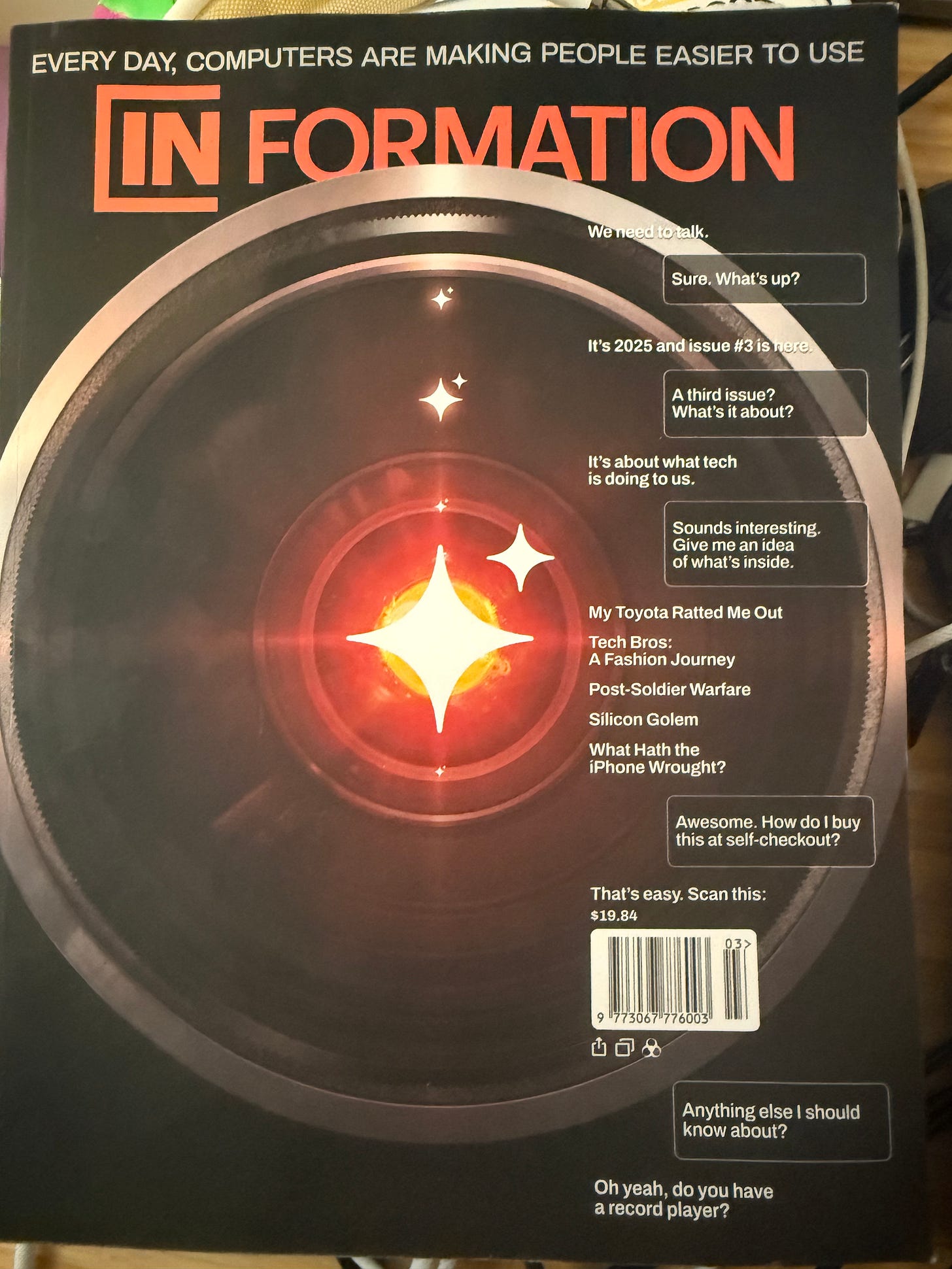

(4) The latest issue of In Formation magazine is glorious, my favorite thing I have read in awhile. It has been 25 years since In Formation was last published. Tech culture has kind of caught up with them in the interim.

The first issue of In Formation was published in the summer of 1998. The New York Times hailed it as “the anti-WIRED.” The magazine’s tagline, “Every day, computers are making people easier to use,” came across as “acutely paranoid” at the height of the midst of the first dotcom boom. The second issue, a “special apocalypse issue” was released two years later. The apocalypse in question being Y2K. Then the dotcom crash happened, and In Formation’s writers became occupied with other things. They recently decided to get the old band back together. I’m so glad they did. (Read John Sundman for more of the backstory. It’s a real treat.)

The magazine feels like an alternate-universe version of vintage WIRED, written by people who are enamored of the technologies being produced by Silicon Valley, even as they remain skeptical of the companies, individuals, and market forces that are shaping the industry. It’s 162 slightly-oversized pages, with a dash of the old day-glo color schemes. The layout and format will all remind you of the tech magazines you read during the golden age of print magazine publishing. It isn’t a magazine for haters — the contributors have all worked in and around Silicon Valley for decades. They love the tech industry and wish it would be better. It’s more a magazine for wistful skeptics.

I honestly can’t decide whether to categorize In Formation as a tech magazine or an art installation. It’s a little of both. The articles contain a mix of critical opinion and straightforward reporting. The piece by Eugene S. Robinson about the unmaking of Carlos Watson and Ozy.com is just flat-out great first-person reporting. But my favorite part of the magazine is probably the parody advertisements. The spoofs on sponsored content ads are remarkably clever. (Ads for the Northwestern Kellogg “School of Micromanagement,” a Brown University Graduate Program in “Critical Techbro Studies,” etc.) There’s also an 18-page graphic novel and a photo essay series by Eric Pickersgill, “The Missing Mirror,” that I keep thinking back to.

The magazine is available on newstands and online. If it sells well, it sounds like the editorial team will make it a regular offering. If the first two issues of In Formation were ahead of their time, then this third one is right-on-time.

I hope you’ll check it out.

"It's cool to get on the computer, but don't let the computer get on you"

In addition to my essay Silicon Valley über alles, which Dave links to in the text, you can also read my contribution to In Formation # 3, 'The varieties of Silicon Valley religious experience' here.

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnsundman/p/the-varieties-of-silicon-valley-religious?r=38b5x&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Although none of us contributors to In Formation received monetary compensation, I was given a couple of boxes of the magazine, and still have a dozen or so copies for sale. There's a link to my 'Buy me a coffee' page at the end of my substack essays.