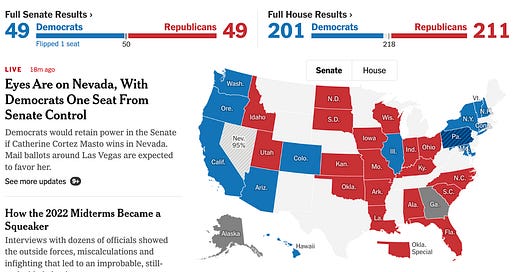

I’ve been holding off on writing about the election because, well, we still don’t even know all the results yet. As I write this, it seems likely that the Democrats will hold the Senate, and even picking up a seat if they win the Georgia runoff. The House is still uncertain — Republicans will probably have a slim majority, but there’s a chance that Dems hold on.

Suffice to say that this went a lot better than expected. The “red wave” turned out to be a trickle.

This is a big deal! I wrote on Tuesday morning that this Election Day would be a test. In a normal off-year election, particularly one featuring low Presidential approval and negative economic indicators, the party-in-power should lose a lot of seats (There’s a whole robust research literature on this topic. If you’re curious about it, ask questions in the comment thread).

The question leading into this week was whether the electorate would treat 2022 as “normal.” The conservative Supreme Court doesn’t usually overturn 50 years of established precedent by overturning Roe v Wade six months before a midterm election. The Republican Party doesn’t usually spend two years denying the results of the past election and defending people who launched an attack on the Capitol.

What we didn’t know a week ago was whether the radicalism of Republican elites would matter at the ballot box. And I think we can now say pretty confidently that it did. Not overwhelmingly so — conspiracists like Ron Johnson were elected to another term — but the emerging wisdom in Republican circles seems to be (1) candidate quality matters (conspiracy theorists win primary elections but lose general elections), (2) The Trump wing of the party endorses too many low-quality candidates, and (3) uhhhhhh, maybe women don’t like having their rights rescinded after all?

The threat to American electoral democracy didn’t end on Tuesday. What happened is that we earned ourselves a reprieve.

There’s an old lesson from my years in environmental organizing that I’ve been reflecting on this week. “When we win, all we win is time. That’s alright, so long as we use that time effectively.”

The insight hit me while studying the history of the movement — I was reading a book about the brave campaigners who successfully protected the Tongass National Forest from clearcut logging in the ‘80s, then I signed into my email account and read an action alert, urging everyone to contact our elected official and ask them to protect the Tongass.

When you are fighting to preserve something complex and fragile, your victories are always impermanent.

Democracy, we have come to see, is complex and fragile.

As an environmental campaigner, this insight led me to focus on trainings and capacity-building. If your wins build a larger movement with deeper commitment and strategic skills, then you have positioned yourself to take on the next fight, which will be harder.

2024 is going to be harder than 2022. If the Democrats do indeed lose the House, that’s going to hurt. Committee chairs matter. If Jim Jordan is a committee chair, he is going to set the personal goal of impeaching President Biden three times in the House. It won’t matter what they impeach Biden for. It won’t matter if the Senate dismisses the allegations out of hand. He’s just going to want to sew chaos and create the talking point that Biden was impeached once more than Trump. A Republican House majority will also hold Biden’s signature legislative victories hostage, threatening government shutdowns and a potential default on the debt ceiling unless he sabotages is his own achievements.

Even if Democrats hold the House, the next two years will be harder than the last two years. It'll mostly be two years of judicial appointments and executive actions. Those two years will be punctuated by Trump judges and a Supreme Court majority inventing excuses to stall or overturn those executive actions. We are, under the best of circumstances, only barely governable. Even with this week’s much-stronger-than-expected results, I suspect we will be no more governable in 2023 than in 2022.

What Tuesday’s victory has earned us is time.

So how do we use that time effectively?

I have three ideas.

One of the themes that I’ve covered a few times on this Substack is that only the Republican Party can fix the Republican Party.

The Trumpist wing of the party (which was an extension of the Tea Party wing, which in turn built upon the Gingrich revolution) is currently dominant. It is a big deal that the few elected Republicans who stood up to Trump (Liz Cheney, Adam Kinzinger) either retired or lost their primary. The Democratic Party is not going to hold power forever. If American electoral democracy is going to continue uninterrupted, the fever has to break within the Republican Party network before they gain power again. The Trumpist/fascist/semi-fascist wing needs to lose power. The anti-Trumpist/not-even-semi-fascist wing needs to gain power. It really is that simple.

I wrote several months ago that this dynamic takes time (“What will it take to actually change the Republican Party?”). Party networks tend to remain stable until and unless they lose multiple elections relative to expectations in a a row. 2018 was a bad year for Trumpist Republicans, but party elites focused on their Senate gains and declared it a draw. 2020 was a bad year for Trumpist Republicans, but party elites blames COVID or outright insisted the election was stolen. 2022 is looking like another bad year for Trumpist Republicans, and we can now see the intra-party fissures taking form.

In this sense, it matters what story gets told about the 2022 midterms. The emerging sense right now is that (1) the Republican party blew it, (2) this was because Trump-endorsed candidates won their primaries but were too extreme for the general electorate, and (3) there was electoral backlash to the Dobbs decision.

Reports are currently circulating that elite Republicans are ready to abandon Trump. But we’ve heard that song before. It’s a catchy but forgettable tune. And it is not at all clear whether abandoning Trump will also mean rejecting Trumpism. Aligning behind another petty tyrant who abandons the rule of law isn’t much of an improvement.

So, for anti-Trump Republicans and people with a media platform, I think it’s important that we use this time to advance the intra-party conflict within the Republican party network. Democrats cannot fix the Republican Party. We are too narrowly divided as a country, and partisan identities run too deep.

The 2022 results create an opening for Republicans to argue that Trumpist politics, with its mix of conspiracism and fascism, is loser-politics. If the anti-Trump wing of the party uses this time to build their power, it will be time well spent.

Democrats cannot fix the Republican Party, but they absolutely can use this time to build and strengthen their own party. I wrote about this topic a few weeks ago (“Rethinking Political Innovation”).

The Democratic Party is operationally much stronger today in Georgia and Wisconsin than it is in Florida and Ohio. The New York State Democratic Party appears to be such a catastrophe that it may have cost the national party its House majority (thanks, Cuomo!). Party-building at the state and local level is tiring, thankless work. But it’s one of the very few things within the party’s control that can improve the party’s electoral chances.

Democratic leaders and major donors within the broader party network can spend the next two years throwing money at flashy political ads and chasing the next innovation, or they can spend the next two years investing in local party-building and infrastructure. I’m convinced the best way to use this electoral reprieve is to build the party’s capacity to identify compelling candidates, register and mobilize voters, and engage citizens in their communities.

I also wrote a few months ago about what I consider to be the fundamental animating conflict in 21st century political contests (“Will the climate crisis be a boon for authoritarians?”). I’ll repost the relevant passage below:

I have suspected for some time that the core philosophical divide in American politics does not map neatly onto a battle between liberals and conservatives. We do not have two competing visions or policy platforms that voters are asked to select between. (The Republican Party does not even have a policy platform anymore – conservatism in America has been revealed as less a coherent ideology than a bundle of simmering resentments.)

What we have instead is two conflicting narratives about government and governance.

The first story goes something like this: “government and governance are fundamentally simple. The reason things have gone wrong is the crooks and idiots in charge. If we just get rid of the crooks and idiots and replace them with the right people, then everything will be fixed.”

You’ve heard this story before. It is the siren song of the authoritarian demagogue. You heard it, almost verbatim, from Donald Trump for years. It’s what he said on the campaign trail. It’s what he said in his convention speech. It’s what he said on Twitter and on television and in public and in private. The government is a mess because of all the crooks and idiots screwing things up. Trump promised that he alone could fix things. He lined up a parade of scapegoats to take the blame when conditions did not improve. He forever looked forward, finding some other crook or idiot to blame. Or he insisted the media coverage was all wrong, that things were in fact going great.

The second story is, in essence, a liberal technocratic narrative: “government and governance are fundamentally complicated. The reason things are going wrong is that governing a large, pluralist society is just really hard and includes a thousand hard-to-navigate tradeoffs. Well-meaning people, trying their best, can make government work better at the margins. But change is frustratingly slow and always incomplete. None of the hard problems can be easily fixed, or else they would have been fixed already.”

(As a political scientist, I am predisposed to believe this latter narrative. If there is one bedrock belief underlying my discipline, it is that government and governance are complicated. That is as close as the field comes to a shared ideology.)

It's tempting to label this a tension between populism and progressivism. But I’d caution that each of those terms has enough baggage and enough competing meanings that it can easily obscure more than it reveals. A full account of left-vs-right populism, and of the historical legacy of Teddy Roosevelt-era progressives is well beyond the bounds of this essay. Instead what I would like to focus attention on here is the rhetorical benefits and limitations of the two competing perspectives.

I am primarily a scholar of strategic political communication. That’s my disciplinary home, though it may be hard to tell from the essays I usually write here. (I’ve been on a bit of a post-tenure detour into other disciplinary conversations where I am very curious and way out-of-my-element.) What has always stood out to me about these two competing ideological perspectives is how slanted the playing field is between the two.

The ”it’s simple” camp has the benefit of much more compelling rhetoric. It contains all the elements of an effective story. There is a hero, a villain, a victim, and a plot resolution. (Elect me. I’ll toss the bums out. We’ll fix the economy/be tough on this problem/make crime go away. Things will all better once I’m in charge.)

What’s more, there are crooks and idiots in positions of power. It isn’t as though every government bureaucrat and politician is a genius/saint. So these stories can get specific, and timely, with news hooks that engage mainstream media and internet drama that can galvanize people on social media.

The “it’s complicated” camp — the defenders of liberal technocracy — have a much more difficult story to tell. “Elect me. We have hard problems, and I can’t make them go away overnight. But together, with time and hard work, we can fix things. It’s going to require patience and fortitude. But the best we can do for one other is to do our very best.”

That story sucks. It’s garbage-fire messaging. It demands daily feats of rhetorical brilliance to make it anything other than a bummer. And it’s a story that keeps being true long after it has lost its news hook and left online publics to wander off in search of more interesting controversies.

The difficulty here is of course that one of these camps is lying and the other is telling the truth. Government and governance is, in fact, complicated.

In the long term, the Democratic Party has to make a compelling case for technocratic liberalism — for the “it’s complicated” story of government and governance.

The most important way you make that case is by governing well and slowly convincing people that democracy is worth all the headaches.

I don’t want to trivialize just how hard effective governance is going to be during this two-year electoral reprieve. It will not be easy.

But, for the Biden administration, I am convinced that good policy will also prove to be good politics.

Student debt relief and marijuana decriminalization were good policies and good politics. The climate bill was good policy and good politics. Do more of this. Govern well, under the theory that your actions will be building blocks for your broader theory-of-government.

Those are the best ideas that I can offer.

Electoral democracy is still at risk. The 2022 midterms were a necessary victory, and a crucial-but-partial step. What we have won is time. That’s all we can ever win.

I hope that time is used by non-Trumpist Republicans to start taking their party back. They have been losing internal fights that they will need to win for this crisis to abate.

I hope it is used by Democrats to build party organization and organizing capacity.

And I hope it is used by the Biden administration to make the case for liberal technocratic governance. The playing field is slanted towards authoritarian populism. Our best hope lies in showing that administrative competence can have real, positive impacts on people’s lives.

The next two years are going to be hard. But we have time. Let’s use it well.

One of the lessons I took away from Counterculture to Cyberculture is that while on some level Stewart Brand is sort of a charlatan, it took a lot of charisma and work to not only re-envision how an entire industry could contribute to the world but also to convince the general public and even a few of the leading lights of that industry to do the same. I'm not sure if there was a Zelig-type in 1920s-1940s Detroit that connected the leaders of the Auto Industry the same way Brand did with tech in California (I think the auto and computing industries are remarkable both in the extent to which they've driven vast social change in the US and world with very mixed results) but it wouldn't surprise me if there was.

The point is that anyone who can successfully sell a view of how the world can change not only to be better but to be qualitatively *distinct* from the present can wind up changing the entire discourse. It wasn't just that a car could take you farther than the streetcar or your horse, but that it would open up a whole new world where you could roam freely through a garden city so different from the crowded working-class urban neighborhood or isolated farm you live in in 1930. It wasn't just that computers connected you quickly to people far away - they were going to create a global countercultural democratic commons that was completely unlike the conservative, phillistine suburb you live in in 1990.

I'm 33, so I was born at the hump of the Millennial echo boom. No one - no one - during my lifetime in the US has tried to offer up a vision of a distinctive, better world other than the computing industry and their publicists. Politicians sure haven't. The Republicans never will. It's no wonder then that so many, including a lot of Democratic politicians, have hitched their wagons to it. Now that the Techlash is fully mature, nothing has risen up to replace it. Meanwhile we appear to be on the cusp of a new energy revolution based on physical, not digital technology. So will liberals and the left take it into our own hands?

Even though I don't live in the US as a Canadian I like to keep abreast of our neighbor's politics because they inevitably have some impact on Canada. I think you've laid out some reasonable frameworks and also made a great point: eventually there will be another Republican president (maybe 2024 or 2028) and the cycle in place for almost 250 years will continue. It would be great if the next Republican president and the rest of their party did not dangerously veer away from the ideal of a stable and productive government by the people, for the people.