Econ blogger/Substack royalty Noah Smith tried his best to defend Marc Andreessen’s techno-optimist manifesto last week, with a 4,000+ word post titled “Thoughts on techno-optimism.” It’s a thorough post, in which Smith offers a more intellectually defensible version of Andreessen’s 90’s throwback tantrum.

I think Smith’s argument deserves more serious engagement than Andreessen’s. And I also find the argument largely unpersuasive. That’s because I think Noah is ultimately a tech pragmatist, like me. It’s just that he isn’t identifying as one (yet).

Here’s why:

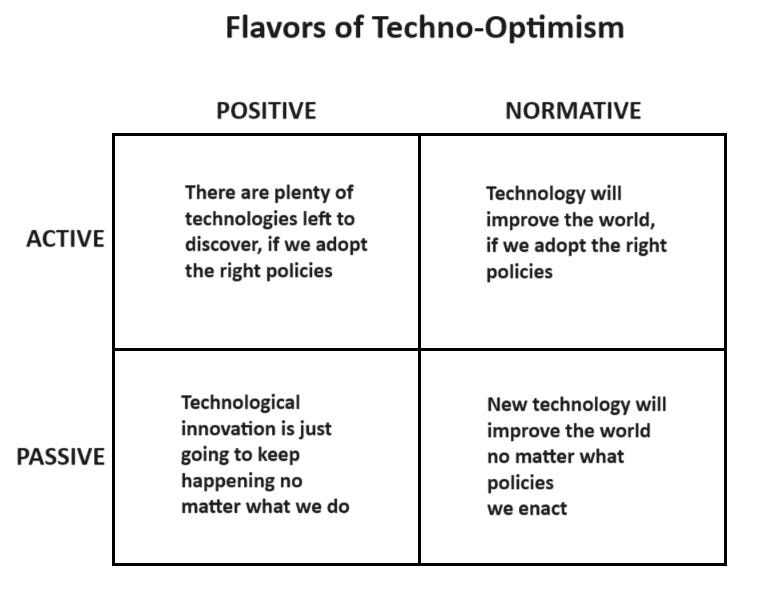

Smith constructs a two-by-two chart of the “flavors of techno-optimism” (see below). He says that you can be a positive or normative techno-optimist, and an active or passive optimist. He considers himself both a positive and normative techno-optimist, but notes “In both cases, though, I’m more of an active than a passive optimist. Whether it comes to sustaining the rate of innovation or making sure that innovations benefit humankind, I think that choosing the right policies is very important.”

I’m definitely no techno-optimist. (I think I’ve made that quite clear in my writing.) And yet I find myself nodding in agreement with both of Smith’s “active” flavors:

Yes, I think there are plenty of technologies left to be discovered, particularly if we provide ample funding for basic scientific research.

Sure, yeah, with the right policies, technology can aid us in improving the world.

But these strike me as little more than a framing exercise! You could rewrite both statements in cranky-pessimist voice and they’d be equally compelling:

Public funding for basic scientific research has been on the decline for years. Conservative elites have politicized scientific research and defunded higher ed. This is bad, and will probably get a lot worse before it gets any better.

We should all be Luddites now! Luddites do not reject technological progress. They insist that we adopt policies that ensure the gains from technology are widely shared. Technology will only improve the world if we alter policies and power imbalances that tech elites (like Andreessen) are jealously defending.

As I wrote last week, “whether you are optimistic or pessimistic really doesn’t matter.” Much more important is what Smith labels “active vs passive” and I would describe as “pragmatic vs ideological.”

I have no quarrel with optimistic tech pragmatists. You think the “Green Vortex” is setting us on a path to reverse the worst impacts of the climate crisis, and so you’re gonna work tirelessly to promote policies that further those efforts? That’s awesome. Let me buy you a beer.

I also find common cause with pessimistic tech pragmatists. You think the near-term impacts of generative AI are going to be terrible, because we are basically just delegating decision-authority to a handful of tech elites who will chase short-term payouts? Yeah… I’m right there with you. First round is on me.

But that’s not the type of techno-optimism that Andreessen is calling for! The main thematic point of Andreessen’s techno-optimist manifesto is that the “techno-capital machine” will inherently improve all our lives, so long as regulators and journalists and trust & safety professionals and sustainability advocates stay out of the way.

And this matters, because there is really nothing “passive” about Andreessen’s optimism. Techno-optimism is, and has always been, a political project. The libertarian tech optimists of 90s WIRED argued that the road to prosperity was paved with low taxes and exemptions from existing regulatory frameworks. Let the builders build, let the capitalists capitalize, let Moore’s Law work its inevitable magic, and the future would be so bright that our spaceships would need shades. Present-day techno-optimists like Andreessen, Musk, and Sam Altman are saying the same thing, hoping we don’t notice how the benefits of digital futures’ past have been apportioned.

Consider the news this week that Cruise — one of the major autonomous vehicle (AV) companies operating in California — has been ordered to halt all operations within the state. This was after a Cruise AV collided with a pedestrian, continued to drive another 20 feet before coming to a stop, and the company subsequentlly lied to regulators about the incident.

I’m pretty confident that Andreessen would say the company did bad, but the regulators are doing much worse by slowing down the pace of AV development. He states in the manifesto, after all, that “Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.” How dare California’s regulators stand in the way of the techno-capital machine? How can they live with such blood on their hands?!?

I suspect Noah Smith would lean toward a more pragmatic response (hell, he wrote another post just last week about needing a “bigger, better bureaucracy.”) AV companies have to be trustworthy. Companies that lie to regulators about accidents are bad, and are responsible for fostering public distrust that will ultimately slow down the rate of tech adoption. There should be consequences for such companies, and those consequences should be meaningful enough to act as a deterrent to similar behavior among its competitors.

That would put him at odds with the techno-optimist political project, regardless of his own optimistic priors.

Marc Andreessen’s “optimism” is a Hero’s Journey where the entrepreneurs, investors, and engineers of Silicon Valley build a tremendous, profitable future unfettered by regulation, taxation, or critical scrutiny. It is a political project, aimed at shielding the investor- and entrepreneur-class from democratic accountability.

We ought to oppose that political project, regardless of whether you personally believe that, with the right policies, technological innovation can improve the world.

So… Noah, let’s raise a toast to tech-pragmatism. First round is on me.

Once upon a time, chemistry was the field of miracles. Aniline dyes, nylon, Teflon, the green revolution in agriculture and others were great advances and proof of DuPont’s slogan, “Better Things for Better Living ... Through Chemistry.” And there was a lot of good that came from chemical progress in the 20th century, likely doing more to improve the lives of more people worldwide than the Silicon Valley has achieved up till now. But during the last third of the 20th century, the toll from poor oversight and lax regulations began to be noticed. Love Canal and Bhopal are famous, but there are dozens of other superfund sites and fatal accidents that occurred during that era. The OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) standard was issue early in my career in chemical manufacturing(1994). It was a direct response to Bhopal and other chemical disasters. My initial reaction, and that of many others, was that the new rule would make chemical manufacturing almost impossible, since it required so much new work that we weren’t doing. But over time, as we learned what the 14 sections of the regulation really meant, it made us better engineers. Rather than moving fast and breaking things (and killing people), we learned to plan better, train better, and made sure everyone went home to their families after work. I expect amazing technological advances to be made in the 21st century, but we don’t need to let tech billionaires experiment of the rest of us without regulations or consequences in order to create a better future.

Great piece, and I totally agree that the "passive" framing is mistaken, as it is only passive if the norms & regulations of the world fit your priors (e.g. unfettered capitalism). In my realm of studying television, I try to debunk the term "deregulation" which became so popular in the 1980s, as more accurately "regulatory shift" - the media industries wanted to eliminate some regulations, like ownership caps and educational programming mandates, but not those that let them make profits, like copyright. Same with Andreessen's ilk - they love the "passive" existing regulations and norms that work for them, decrying those that threaten them (like safety and accountability).